Kalembe Ndile and the Kariokor tyre men: A story of survival, skill and silent impact

Tyres aren’t made to be easily cut—they’re industrial-grade, built to withstand weather, friction, and heavy loads, which is exactly why Kalembe Ndile values them so much.

By the dusty roundabout where Kariokor Market, Gikomba, and Eastleigh meet, a quiet revolution is taking place—not in boardrooms or on billboards, but under the open sky, amid the scent of burnt rubber, sweat, and relentless determination.

Most of you have likely passed by there, whether coming from Eastleigh, crossing from Gikomba, or heading to town through the Bus Station route.

More To Read

- Court hears how police surveillance systems tracked suspects in Ahmed Rashid murder case

- Residents demand action as borehole drilling company renders Yusuf Haji Avenue impassable

- Safaricom’s Ndoto Zetu initiative elevates maternal health in Kamukunji's Eastleigh with bed donation

- Eastleigh residents slam City Hall over shoddy repairs on Athumani Kipanga Street, demand permanent fix

- Mahiza Cafe and Bakery: Eastleigh’s chocolate and dessert factory serving pistachio dreams, boba, and halal elegance

- How Eastleigh rewrote its colonial name into a Kenyan-Somali powerhouse

And at some point, you have glanced at that roadside scene, a group of men and women hunched over worn-out tyres, cutting, stacking, sorting. And you have probably asked yourself: “What exactly are these people doing with old tyres?”

Well, that is the same question that drew me in.

What started as a passing curiosity became a story that opened my eyes, not just to the work itself, but to the people, the passion, and the powerful impact behind it all.

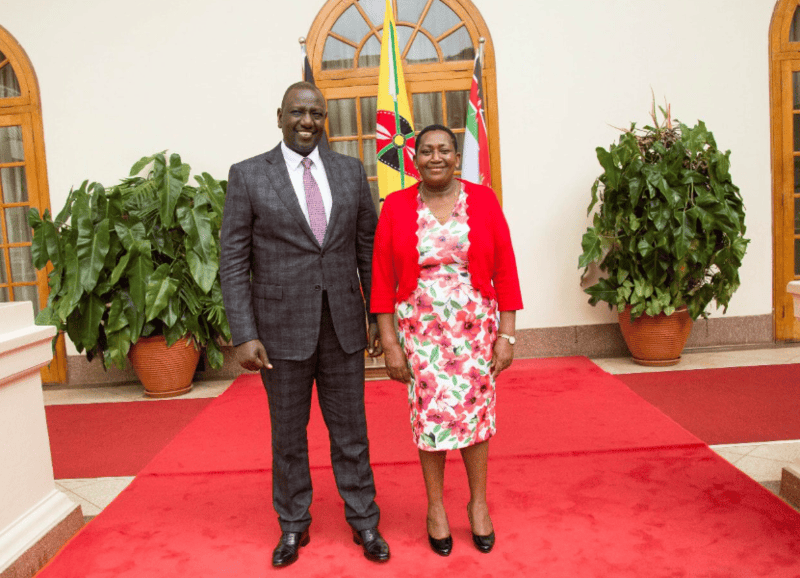

Here, surrounded by heaps of discarded tyres that once roamed Kenyan roads, stands Wandile Musyoka, better known by his inherited nickname, Kalembe Ndile.

Born in 1975, Wandile is a father of three, a self-taught craftsman, and a man whose story is as textured as the tyres he works with.

Since 2000, he has built a living, perfected his craft, and created a system from what most people call waste.

Nobody taught him how to do it. There was no manual, just life, hunger, instinct, and the will to survive.

“Once you put your mind and energy into something,” Wandile tells me, pausing to wipe the sweat from his brow, as he carefully sharpens his knife with a stone.

“It somehow works out. And that is the beauty of life, Margaret.”

A life carved from tyres

From as early as 6 a.m., Wandile is at his station, a triangle of sun-scorched ground near the roundabout.

Some days he has already worked the night shift and extends during the day; others, he is strategising for the next day’s orders, sorting rubber, cutting it with sharp knives, loading sacks, or simply catching a few minutes of rest on a stone under the sun.

The job is not for the faint-hearted.

Tyres are not designed to be easily cut; they are industrial-grade material made to endure weather, friction, and load, exactly why Wandile finds value in them.

With layers of black rubber stacked around him, he carves carefully, every movement deliberate.

Balanced on his arm, the rubber strip becomes both shield and canvas as he slices through it with rhythmic precision, almost poetic.

You can tell he has done this for years; the movements are effortless, instinctive, like muscle memory carved from experience. At some point, he handed me one of his blades, small, sharp, and worn from use, and told me to try.

I gripped it, pressed it against the tyre, and instantly realised how difficult it was.

The rubber resisted, thick and stubborn, and one wrong move, and you could slice your arm. My hands trembled, and I gave it back.

This was not just cutting, it was control, technique, and respect for the material. What he made look easy was, in truth, a skill forged over decades.

The rubber strips used by boda boda riders to tie goods on their motorbikes. They are more preferred than ordinary ropes due to their durability. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

The rubber strips used by boda boda riders to tie goods on their motorbikes. They are more preferred than ordinary ropes due to their durability. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

Yes, I love my work

He does not speak of his work as a struggle; he speaks of it with pride, like an artist discussing his canvas.

People think it’s just cutting,” he says, gripping the blade with practised ease.

“But it’s not. It’s your whole body, your grip, your balance, your timing. And your mind has to be sharp too. You have to know the tyre, feel the resistance. It’s physical, yes, but it’s also a skill. Experience is very much comes in very handy, so you don’t just wake up and do this. You earn it, one cut at a time, sweat, focus. That is the beauty.”

Next to him is Ngutho Malonza, who introduced me to Wandile’s nickname.

I had always associated the name Kalembe Ndile with the late politician from Ukambani, but here, it means something more; it signifies hustle, humour, and humility.

Wandile laughs off the name, saying his father gave it to him as a joke, and it stuck.

As we talk, he gets a call on his battered keypad phone, popularly known as kadunda; he has no smartphone with flashy apps.

Race against time

He tells me he and his team are currently working on a batch of orders from Kisii, Sotik, Thika, Meru, all waiting on tyre strips, all with deadlines hanging over his head like the Nairobi heat.

“It’s a constant race against time,” he tells me, eyes fixed on the strip in front of him.

“We don’t have the luxury of formal breaks or long lunches.”

He lifts a mandazi in one hand, a metal cup of lukewarm tea in the other, and he sips and drinks and gets to work. Even as we chatted, the blade never left his side.

He chews between cuts, not out of comfort, but survival.

“If I stop,” he says, “the day wins.”

Then, without looking up, he adds quietly,

“Tomorrow brings new orders. But these, these have to leave today by 7 p.m.”

Akala sandals made from old tyres. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

Akala sandals made from old tyres. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

Mastermind

He is not just overseeing the whole operation, he is in the thick of it, sleeves rolled, hands calloused, guiding others with his presence more than his voice.

There is no clipboard, no uniform, no title there, but somehow, everyone around him knows who is leading.

“Everyone knows what he is handling, so, no time for slacking and micro-managing. I have to ensure orders come in, orders arrive, source materials, and even help the team in making these orders,” he tells me.

You can see it in the way they pause when he speaks, the way they ask before tying a gurney sack, the way he stops to check each cut.

He balances roles like he balances the strip on his arm, effortlessly, but with intent.

In this space, time is currency, and rubber is life.

Boda boda operators want his rubber strips for tying goods on their motorbikes; companies and people want sandal soles; farmers need rubber accessories that will not rot in the rain.

Self-made system, self-made impact

Wandile does not train his workers formally. Instead, he hands them a knife and lets them figure it out by watching him work. That is how he learned. It is not negligence; it is a philosophy, his philosophy.

“If you want to survive, you learn. No one held my hand. If a man is willing to work, not beg, I’ll give him a chance. Work, earn your coin, and be a man at the end of the day.”

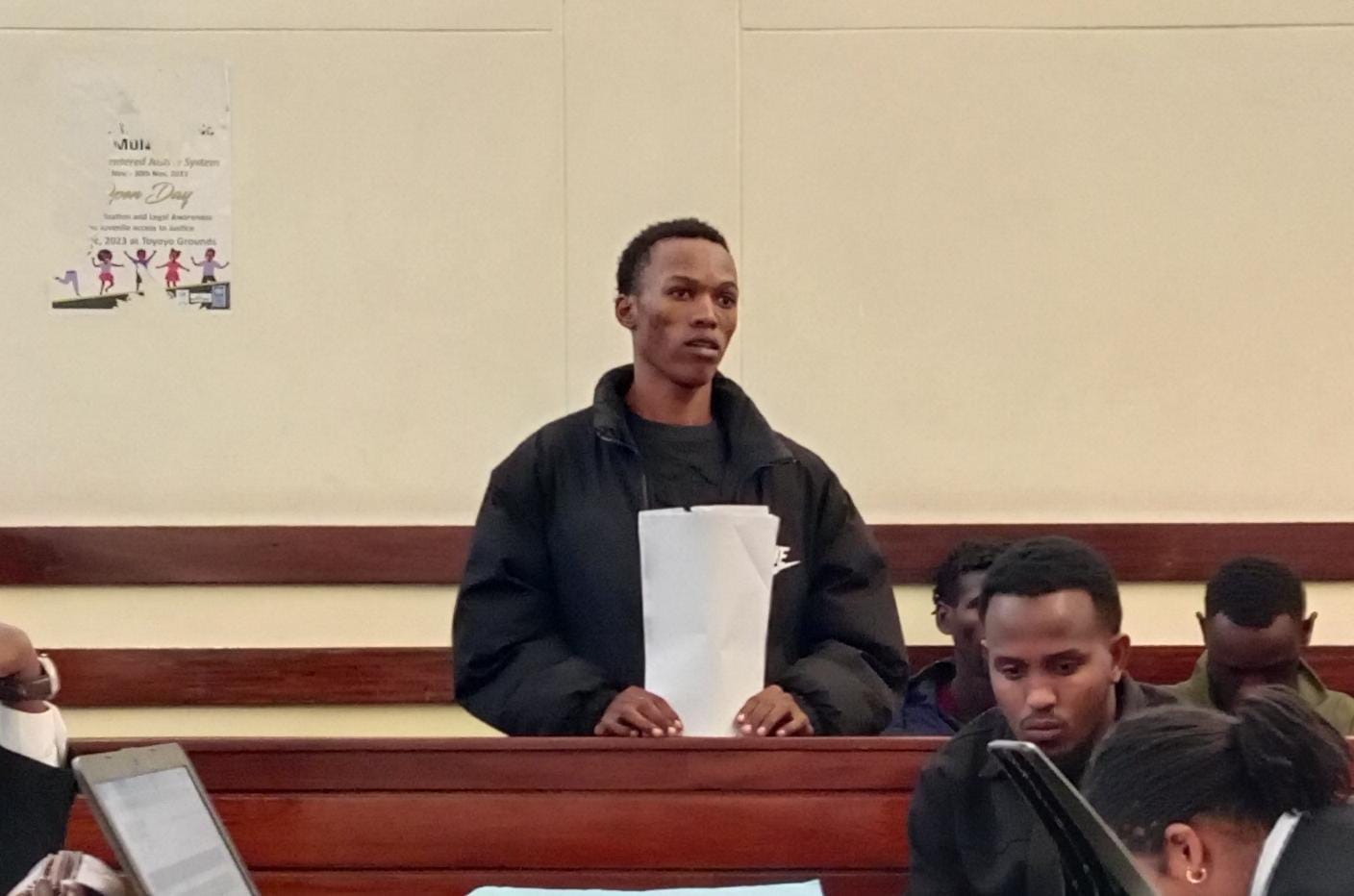

He operates on a commission system, employing both the youth and the elderly.

I met people as young as 22 and others as old as 70 working alongside each other, men and women.

In this open-air workshop, dignity comes not from appearance but from effort.

Just a few meters away, idle men slept on the grass by the roadside.

Wandile pointed at them, his face expressionless.

“Some will lie there all day, then ask for help. But I respect anyone who tries, even if they fail, because trying is self-respect.”

Pushed out

Their working area used to be inside Kariokor Market, but county regulations pushed them out. Now, they work under open skies, exposed to heat and rain. Wandile pleads for a shed where to work from.

“Rain ruins everything. And the sun burns us, if we had shelter, we’d be unstoppable.”

From waste to wealth

Wandile’s work goes far beyond just making a living, it is a quiet battle against one of Nairobi’s, and indeed the world’s, most stubborn environmental foes: discarded tyres.

These tyres, left to rot, linger for decades, sometimes 80 to 100 years, poisoning the earth beneath them.

They seep harmful chemicals into the soil, clog up our land when burned, a common fate in many informal settlements, and they release clouds of toxic smoke.

This smoke does not just pollute the air; it carries poisons that cause respiratory illnesses and drive climate change.

But Wandile is turning that story upside down.

Fighting pollution

With every tyre he cuts, every strip he repurposes, he is doing more than just crafting sandals and rubber goods; he is cleaning the city’s streets, reducing hazardous waste, and fighting pollution in a way that is rarely seen or celebrated.

The work is dangerous. Some tyres are laced with metal wires, sharp enough to cut deep. That is why Wandile and his team wear thick rubber protection on their arms and legs, not just to shield from the harsh friction of rubber, but to guard against injuries from jagged steel strands hidden in worn-out treads. Every cut is precise, measured. A wrong move can cost blood.

What he is practising is the essence of a circular economy: breathing new life into what others discard as worthless.

Where most see "garbage”, Wandile sees opportunity, transforming end-of-life tyres into products that carry new value, new purpose, and a second chance.

In a world drowning in waste, his hands are crafting a solution, one slice at a time.

Kariokor market: Where rubber becomes akala

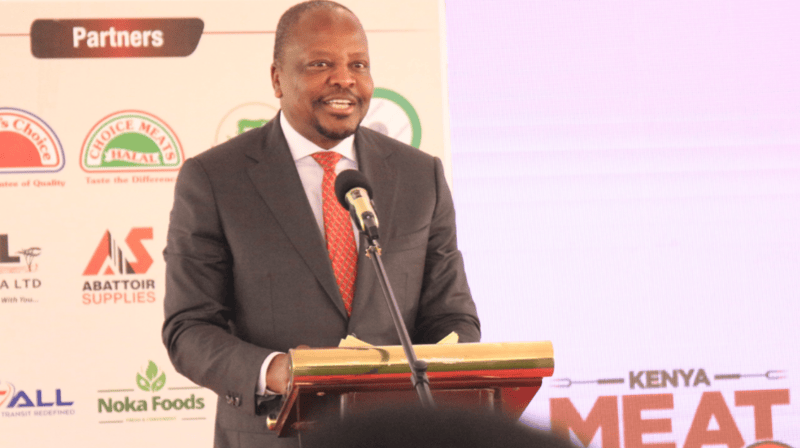

Wandile directed me deeper into the market, to a workshop hidden behind corrugated walls and rows of stalls, where I met Kituku Nzioka, another legend in the informal shoe-making trade.

Inside his shop, the air is thick with rubber dust and the sound of measured hammering. Kituku, now in his 60s, has spent more than two decades crafting akala, open-toed sandals made from recycled tyres, famously worn by pastoralist communities like the Maasai.

“They love them because they last,” he tells me.

“Especially the Maasai and the Samburu, who are always on the move, these sandals don’t wear out quickly; they’re made for the road.”

The term akala comes from the Luo community, but these sandals are loved by many. They are tough, practical, and affordable.

Just one strip from a lorry tyre can be transformed into up to 10 pairs of sandals.

Kituku tells me the prices range from Sh100 for children’s sandals (when bought in bulk) to Sh350 for adult pairs, making them a durable and budget-friendly choice for many.

Kituku shows me a strip, then traces a foot pattern using a metal template.

Around him, four other workers eat their lunch while working, eyes on the prize, hands never idle.

“These hands are scarred, calloused, marked by years of hard work. They’ve carried the weight of my family’s dreams and struggles for 20 years. Every cut, every callus tells a story of sacrifice, sweat, and love. These hands may be rough, but they’ve never failed to provide,” he says.

Tyre scarcity

Like Wandile, Kituku also battles to find quality tyres for his work.

The closure of Firestone’s tyre manufacturing plant in Kenya dealt a heavy blow to artisans like them.

With local production halted, the supply of affordable, durable tyres dwindled, forcing them to rely on imported or local tyres that are often more expensive and harder to source.

This scarcity has made their craft even more challenging, impacting their ability to meet growing demand.

The thread-based tyres, known locally as uzi, are prized for their flexibility and ease of shaping, but they are expensive and hard to come by.

On the other hand, wire-based tyres are more common but much tougher to process due to their rigid structure.

That is why, Kituku tells me, in this business, you cannot do everything.

“You either focus on cutting and sourcing, like Wandile, or on crafting, like me,” he says. “Trying to do both is too tedious, it takes too much strength, too much time. You have to choose your lane and master it.”

Different tyres also come with varying tread depths, which affects both the durability and the products made from them.

For example, tractor tyres have deep, heavy treads designed for rough terrain, making them incredibly durable but also rare and costly since not many people own tractors.

When one shows up in the market, its value shoots up.

Similarly, tyres from lorries, Land Rovers, and cars vary in size, thickness, and tread depth.

“Lorry tyres are thick and sturdy, perfect for heavy-duty goods, and expensive, while car tyres are thinner and easier to cut but produce less material,” he says.

“These differences influence not only the price but also the kind of products that can be made from each type.”

Calls for change

He also calls out for change: better drainage to prevent sewage flooding during rains, access to piped water (essential when cutting rubber and for drinking), and most importantly, a market.

“If our Starehe MP, Amos Mwago, could help us export these sandals, even around East Africa and beyond, it would change everything. We have the skill, we just need the platform.”

The soul of hustle

What struck me most was not just the work, but the philosophy behind it.

As Kituku told me, holding up a Sh200 note: “This money doesn’t announce where it came from. Whether you cut tyres or sit in an office, at the end of the day, you use it to buy bread. Same bread, same cost. So why should we look down on any job?”

That moment silenced me.

It reminded me that dignity is not defined by a title; it is found in effort, resilience, and the ability to create something out of nothing.

Wandile and Kituku are not just surviving; they are building a micro-economy, providing employment, preserving the environment, and restoring a sense of purpose to people who would otherwise be written off.

Respect the craft

In a society that often glorifies suits and Wi-Fi, there is something deeply humbling about watching a man turn a tyre into a sandal with nothing but a blade and resolve.

It is not glamorous, but it is honest. It is not easy, but it is real.

Wandile and Kituku represent an ecosystem we often ignore, the invisible economy of Nairobi’s streets, where sweat becomes salary and rubbish becomes revenue.

Next time you see someone cutting tyres at a roundabout, do not look away.

They are doing more than you think.

They are protecting the planet.

They are feeding families.

They are proving that dignity, after all, can be made from rubber.

Top Stories Today