Ali Kony and the twilight of the Lord’s Resistance Army

Ali was one of his father’s closest sons as well as the LRA’s so-called minister of foreign affairs. He helped thrash out peace deals with other rebel groups and traded ivory with merchants from China and Yemen.

Not long ago, Ali Kony, a neatly dressed Ugandan man in his early 30s, was primed to take over from his father as the head of an infamous armed group that had spent the best part of four decades sowing fear across swathes of central and east Africa.

Yet one morning last year, he sat reclined on a worn beige leather sofa in a small house in a peaceful Ugandan town. Pink, purple, and green Christmas tinsel hung off the walls as Ali’s children darted in and out, showing off their homework to a proud father.

More To Read

- Uganda agrees to take migrants under US deportation deal

- Uganda bets on $250 million Chinese-owned gold mine to drive economic growth

- Uganda’s NUP moves to court to block civilians being tried in military courts

- 20-year-old student announces bid to unseat Museveni in 2026

- Ugandan opposition leader Kizza Besigye denied bail as treason trial drags on

- Kenya, Uganda to sign cross-border deal to end Turkana-Karamojong clashes

Ali, it appeared, had chosen a different path.

“I grew up there, I had children there, I had spent so much time there,” he said of the hardscrabble rebel camps where he had lived almost since birth. “I thought of having another life.”

Born in the early-to-mid 1990s, Ali was until recently one of the most senior figures in the Lord’s Resistance Army, the rebel group created in northern Uganda in the second half of the 1980s and led by the self-styled spirit medium, Joseph Kony.

Ali was one of his father’s closest sons as well as the LRA’s so-called minister of foreign affairs. He helped thrash out peace deals with other rebel groups and traded ivory with merchants from China and Yemen.

Yet a privileged life within the LRA – once one of the world's most notorious militia groups – was not the life Ali wanted. He slipped away from an LRA camp four years ago, spending time in a Sudanese border town before – in mid-2023 – returning to Uganda, where he met President Yoweri Museveni and eventually joined the national army.

The story of Ali’s topsy-turvy defection and what has proved to be a hard homecoming – revealed in detail for the first time by The New Humanitarian – is indicative of the story of the LRA writ large.

Over the past decade, hundreds of worn-out LRA members have trodden a similar path to Ali, abandoning the group and leaving Joseph Kony with no more than a couple dozen remaining fighters. Once focused on overthrowing Museveni, and once known for its extreme acts of violence, the LRA now has more prosaic concerns: staying alive.

Yet Ali’s defection is more significant than his peers. That somebody considered to be Joseph Kony’s successor should leave the LRA shows that even the leader’s inner circle is now crumbling. It is a sign that one of Africa’s longest-running rebel insurgencies is now on its very last legs.

How long it might still last, though, remains anybody’s guess.

Though Joseph Kony is ageing and often unwell with diabetes, he is still viewed by Ali and other current and ex-rebels as a messianic figure with political and spiritual powers. And while the LRA is all but defeated, Ali’s descriptions of how the group survives in the margins demonstrate how remarkably endurant its rump of remaining members are.

In Uganda now for nearly two years, Ali’s life outside the LRA also shows the challenges that ex-combatants face. Once a brigadier with multiple business ventures, Ali is now barely known to the local community. His children have been getting sick from unfamiliar food, and from cold weather they aren’t accustomed to.

Still, Ali does not regret his decision to leave. “I have a love for my father, and I would have liked to have stayed with him,” he told The New Humanitarian. “But I have my own vision… to see cities, maybe to travel to other countries where nobody shoots you or can arrest you.”

LRA 2.0

The New Humanitarian met Ali early last year in a rented house in the northern Ugandan town of Gulu, which was once the epicentre of the LRA war. The rebels claimed to protect the local Acholi community in the north against Museveni’s regime, but they often turned against their community, driven by a violent messianic ideology.

Soon into its insurgency, violence became an end in itself for the LRA. According to the UN, the group was responsible for more than 100,000 deaths and the abduction of up to 100,000 children. Kony and other commanders received the first International Criminal Court arrest warrants, in 2005. They were widely portrayed as evil incarnate.

Over time, the LRA was pushed out of Uganda to neighbouring states. Further military pressure fragmented the group, and a Ugandan amnesty law encouraged defections. Its political message waxed and waned, with complaints about Acholi and northern Uganda’s marginalisation mainly emerging during peace talks. Its numbers, meanwhile, faded as experts joked there were more LRA analysts than rebels.

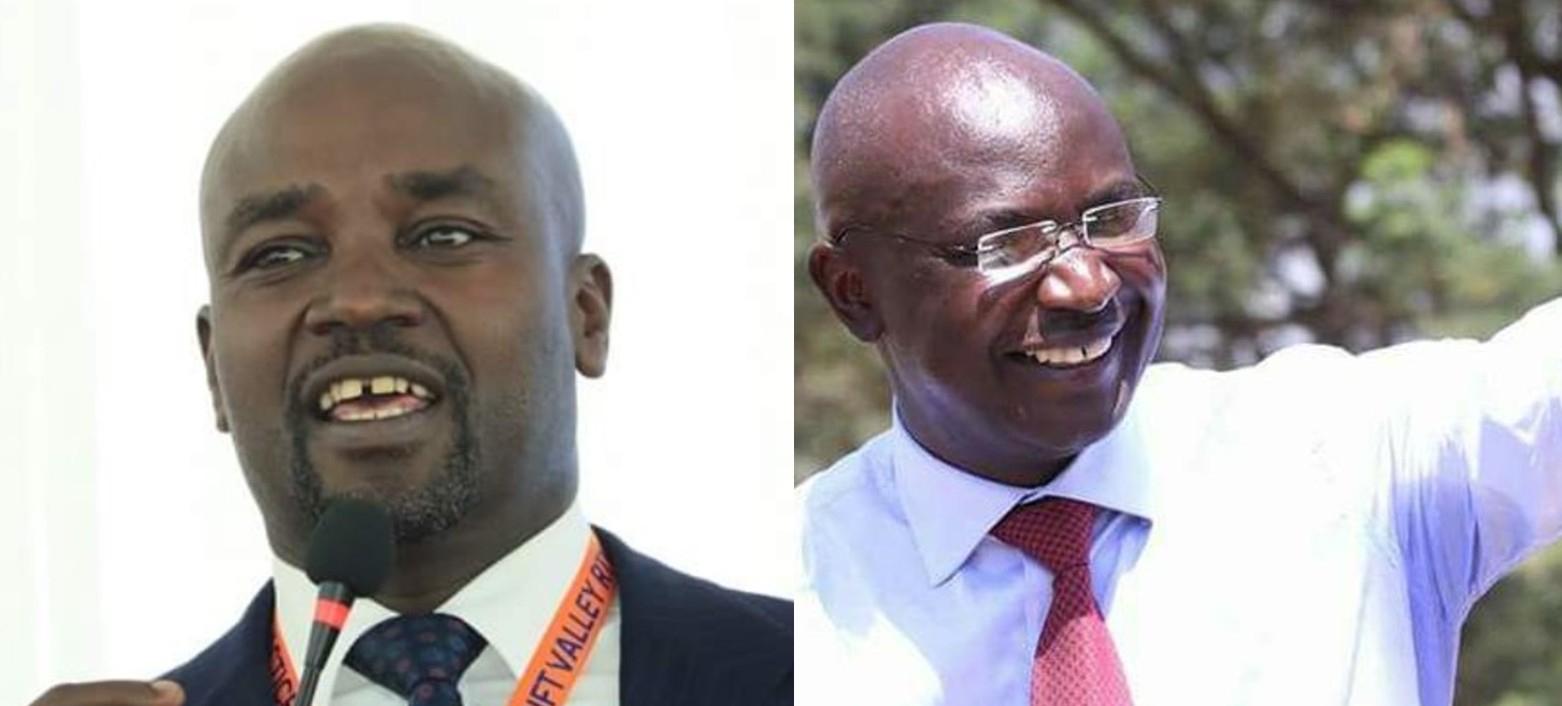

Joseph Kony (pictured in the white shirt) calls for a ceasefire at a rare news conference in Nabanga, Sudan, on 1 August 2006. (Photo: Adam Pletts/Reuters)

Joseph Kony (pictured in the white shirt) calls for a ceasefire at a rare news conference in Nabanga, Sudan, on 1 August 2006. (Photo: Adam Pletts/Reuters)

Still, the group remained active, surviving in a hard-to-reach contested border zone (the Kafia Kingi enclave) between Sudan’s Darfur region and the Central African Republic. To evade capture, the group remained mobile and changed its modus operandi, reducing abductions and looting, and relying instead on agriculture and illicit trade.

Ali became a central figure during this transition – of which little has been written – cultivating business networks and integrating the LRA into a regional black market underworld that helped the group operate under the radar. His story is therefore also a story of the LRA 2.0 – one that defies media stereotypes of an often secretive group.

In Kafia Kingi, the LRA’s rear base from 2010, Ali was involved in sourcing ivory from local traders, and from local hunters who would “kill the elephants, bring the tusks and sell it to us”. Ali traded with merchants from around the world. It was, he said, “a booming business”.

Ivory earnings were supplemented with income from gold, which Ali bought from markets in Darfur and flipped to Sudanese traders, and from marijuana, which he sourced from local growers and sold on to “big businessman”.

Life had a more mundane side too. The group grew cassava, maize, beans, and pumpkins, and made money selling honey to locals. Bees were expelled from hives using fire (“making them drunk, so they escape and won’t bite you,” Ali said) and with chargers from rocket-propelled grenades: “remove the charger, throw it in the hive, making them drunk and harmless – you can even put your hand in there,” Ali added.

While running business matters, Ali said he also worked as the LRA’s foreign affairs minister, a role confirmed by other former LRA combatants and reflected in his fluent Arabic and various nicknames – “Bashir” [after the ousted Sudanese dictator] and “Caesar” [after the Roman general].

Ali said his portfolio included forging non-aggression pacts with other armed groups in the area. Some pacts included trade agreements and deals to exchange intelligence and protection. He described them as some of his biggest achievements with the LRA.

Of course, not everything about the LRA changed in this period. Abductions and looting still took place, while Ali and others retained faith in Joseph Kony’s power. Ali said his father predicted COVID-19 and even shared a premonition of him in Gulu.

Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony in Sudan with his children in 2008. (Photo: Reuters)

Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony in Sudan with his children in 2008. (Photo: Reuters)

Though Ali and others helped the group transform and survive the dangerous borderlands, life also remained tough. Until 2017, the group was still being tracked by the Ugandan and US armies, and deadly firefights with other armed groups were common. Defections happened regularly – and even Ali was considering his options.

An unusual escape

Ali described his motivation for eventually leaving as two-fold: to build another life for himself and his children, and because of a conflict between his mother (who lived with the group in Kafia Kingi) and father. It is unclear what the conflict was about, but Ali perceived it as potentially life-threatening.

The circumstances of his escape are grey, though Ali said he and his family (which included four children, his wife, and his mother) slipped off secretly at night, leaving in small groups so as not to arouse suspicion.

Ali’s next steps were also unusual. Most ex-LRA members surrender to the local authorities in their place of defection, but Ali and his family instead travelled to a Darfuri town called Songo, only 80 kilometres from the base camp they had escaped.

Ali knew Songo well. It used to be an ordinary market area, but the discovery of gold in recent years has transformed it into a border boomtown. From the moment the LRA settled in Kafia Kingi, Ali and other LRA forces would travel there to trade.

Ali’s life in Songo echoed the one he had left behind. He traded gold and cannabis, acting as a middleman for both. He owned shops, farmed sorghum, groundnuts, and sesame nuts, and even worked as a taxi driver.

It is unclear how long Ali planned to stay in Songo (or if indeed he intended to leave), but his hand was forced: In April 2023, conflict erupted in Sudan between the Rapid Support Forces (a paramilitary group with a stronghold in Darfur) and the Sudanese army.

Ali and his family crossed into South Sudan and started a long journey to the capital, Juba. “Along the way, we encountered many difficulties,” he recalled. “Where to sleep, how to pay for food; one of our children was sick with malaria.”

Weeks after arriving in Juba, his money exhausted, Ali went to the Ugandan embassy, where he presented himself as a businessman who had been working in Sudan rather than the son of Joseph Kony. The ploy worked and he obtained a travel permit.

Soon after, Ali was on the road to Gulu.

A difficult homecoming

Ali was born in Gulu but brought to the LRA when he was six months old. From then on, he would hear about life in the town from his mother, and from other visitors who had come to meet the group in the bush during different peace talks with the Ugandan government.

His expectations of returning were high, as they are for many former LRA fighters: Their isolated existence often gives them an idealistic sense of what life will be like outside of the group.

When The New Humanitarian met Ali last year, however, he was in a kind of limbo, waiting for his life to restart in a rented house where electricity was unstable.

A few months earlier, Ali had been invited to Museveni’s state house and promised a range of benefits: 30 acres of land, a farm, and houses for his family. “The president welcomed us, and told us to feel at home; he told us this is our country,” Ali said.

But the benefits didn’t materialise. Three months later Ali held a press conference appealing to Museveni to honour his word. His wife Selly (who is Congolese and was abducted by the LRA) said the family “sleep hungry or just survive on a meal per day”.

Ali’s experience is not unusual for former LRA fighters. While the group still holds a mythical status in Uganda, and Museveni sees political capital in bringing ex-LRA home (or at least being seen to), he rarely comes through on his promises of support.

And though Uganda has an amnesty law for the group that reflects the generosity of Acholi society, former LRA members still face discrimination, with children seen in schools as troublemakers, and women often struggling to marry or remarry.

Ali hasn’t faced discrimination, although he has struggled to adapt. “When I came back, I tried to adjust, but it was very hard,” he said. “In the LRA, I had things at my disposal… I had a high rank, and being a son to the top LRA commander, I had respect from other LRA.”

One livelihood option often available for defectors is to join the Ugandan army, which tends to see ex-LRA as disciplined fighters. In one interview, Ali suggested that wasn’t what he wanted (“I left the LRA because I was tired of military work,” he said) but after joining late last year he appeared satisfied by the benefits of a monthly salary.

Could a similar life be tempting to the other remaining LRA combatants? What about Ali’s father, of whom rumours of surrender talks occasionally surface (though they are often scams by entrepreneurial Acholi looking for a payout from diplomats and NGOs)?

Ali said he does not know what is in their minds.

“Some may be afraid, because of some of the things they have been told about this government: that they will arrest you and put you in jail; and maybe you will get poisoned,” he said.

Still, Ali is confident in his choice.

“I looked deep and long,” he told The New Humanitarian. “I needed to go home”.

Written by Kristof Titeca, Professor at the Institute of Development Policy at the University of Antwerp. Edited by Philip Kleinfeld.

Editor's note: Kristof Titeca has been interviewing former members of the Lord’s Resistance Army for the past 20 years. He has produced a visual book about life inside the rebel movement and has written many academic articles on the group.

Top Stories Today