Thread by thread: Kariokor’s women weavers stitch culture, resilience, and hope into every bag

They dream of formalising the supply chain, getting access to e-commerce platforms, establishing collection hubs, and maybe even starting their own export cooperative.

In the maze of stalls and scents that make up Kariokor Market, a quiet revolution is underway.

Here, women gather with coils of sisal and boundless determination, turning natural fibres into bold, beautiful bags that carry stories as much as they carry goods.

More To Read

- From waste to water tanks: How Kariokor youth are turning Nairobi’s trash into livelihoods

- Kalembe Ndile and the Kariokor tyre men: A story of survival, skill and silent impact

- Forging the future: How Kelvin Kimuyu is reviving brass craft in Nairobi’s Kariokor Market

- Kariokor residents protest over garbage, burst sewers and Sakaja's inaction

- Mazingira Day: How Kariokor's old tyres dealer is helping safeguard environment

- Unbowed: Umeme FC’s battle to maintain club’s rich heritage amid financial difficulties

Among them is Jane Mwende, a seasoned artisan whose weathered fingers move with quiet precision. To her, they are not just crafting bags. They are weaving stories of cultural memory, economic resilience, and shared sisterhood.

At the heart of this network is Mwende, the 48-year-old soft-spoken but steely artisan whose hands bear the calluses of a fifteen-year craft journey that began in her native Ukambani.

“My mother wove mats. She was a member of a women’s group that was sponsored by white missionaries back in Ukambani,” she says. “But I chose bags. I wanted something bold, something that would carry our culture into the future.”

Mwende says the demand for their bags largely comes from two main markets: Nairobi’s urban boutiques and the Kenyans living abroad. In both cases, the women have learned to navigate an informal but functional distribution system.

“We package the bags ourselves, usually in reused cartons or gunny bags,” she explains.

“Then we send them through matatus or long-distance buses to Nairobi town or directly to clients in places like Thika, Kitengela or Nakuru.”

Designated collection points

In Nairobi, the packages are dropped off at designated collection points, usually bus stages or roadside shops, where buyers or middlemen pick them up.

It is a trust-based system, but one that has worked for years.

“Sometimes we only know the buyer through WhatsApp,” Mwende says.

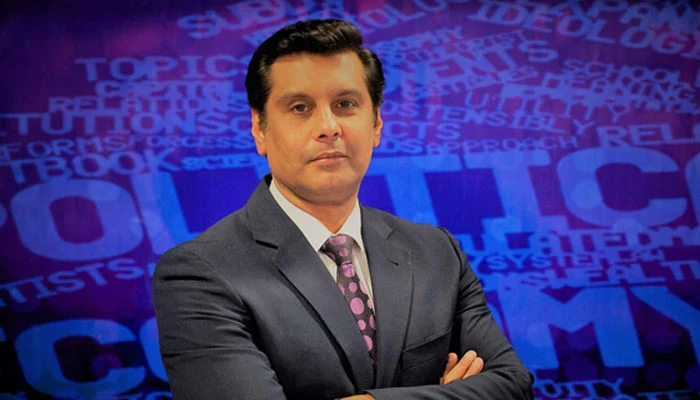

To keep up with shifting tastes, the artisans have started blending sisal with cotton, creating softer, more versatile designs. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

To keep up with shifting tastes, the artisans have started blending sisal with cotton, creating softer, more versatile designs. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

“They send the money once they get the goods. We have to trust them, and they have to trust that our bags are quality.”

The diaspora market, she says, is a growing but delicate opportunity.

“Kenyan women living in the UK, US, Qatar, and Germany often order in bulk for resale during cultural festivals, summer expos, or online pop-ups. But shipping is expensive and unpredictable, so at times, we tell them to cover the shipping cost, which they openly do.”

“One time we lost a whole parcel to customs,” she recalls. “That was a big loss. So, now we try to work with people who travel. We send bags through relatives or friends flying out, but that can be limiting at times, especially if the order is big.”

Despite these challenges, Mwende remains hopeful.

They dream of formalising the supply chain, getting access to e-commerce platforms, establishing collection hubs, and maybe even starting their own export cooperative.

“Right now, we are doing it our way, the hustle way,” she says. “But imagine what we could do if we had support in logistics and marketing.”

But now, she is in Kariokor, Nairobi, where she does things differently.

Her stall is neatly lined with brightly coloured handbags, some striped like the Kamba kikoi, others dyed in earthy reds, browns, purples, ocean blues, and greens that nod to nature.

Each one takes up to three to five days to complete, she tells me.

“This is more than a job. It’s our heritage,” Mwende says. “A bag is not just a product. It’s a message. A memory. A prayer that someone, somewhere, will see us.”

The art of sisal

Sisal, a hardy agave plant once synonymous with colonial-era cash crops, has found new life in the artisan economy.

While large-scale plantations have declined, smallholder farmers in Kitui, Makueni, and Kilifi still grow and harvest it, supplying raw fibres to cooperatives and markets like Kariokor.

Here, the process is intricate: fibres are cleaned, dyed using both natural pigments (from charcoal, turmeric, and onion skin) and synthetic colours, sun-dried, then rolled into thread.

Weaving is done entirely by hand, no machines, no shortcuts. So, the women weave, layer by layer, depending on how big or wide they want the basket, and the designs they need to incorporate.

“It’s labour-intensive,” says Mwende, demonstrating the kĩondo spiral technique.

“But it calms the heart, and doing that surrounded by women around me as we gist, share ideas, it keeps our minds strong.”

More than just craft

Many of Kariokor’s weavers are single mothers, widows, or women who were edged out of formal employment.

Sisal weaving offered not just an income, but dignity. On a good month, Mwende says she used to sell 8 to 10 bags, earning between Sh500 to Sh1,200 per piece, depending on the piece.

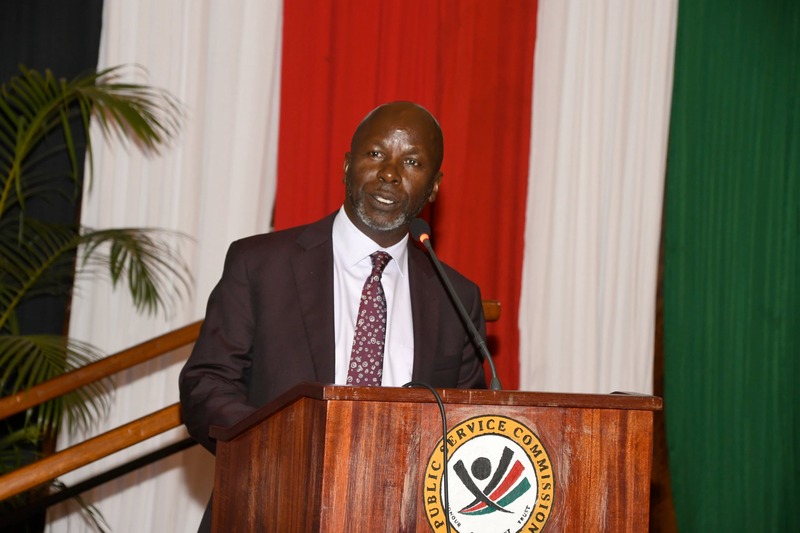

Weaving by Kariokor’s craftswomen is done entirely by hand, no machines, no shortcuts. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

Weaving by Kariokor’s craftswomen is done entirely by hand, no machines, no shortcuts. (Photo: Margaret Wanjiru)

“Back then, the business was doing well, we were making good money,” Mwende reflects. “But when Covid hit, everything changed. Orders stopped. Many of us couldn’t afford materials or even stall rent. And now, with the economy still struggling, we’ve had to improvise just to survive.”

“We’ve started selling online, reaching out to clients beyond Nairobi. Some of us are even approaching tour companies and hotels that host tourists, hoping they can stock or showcase our bags. We’re doing everything we can to keep this business alive, because honestly, this is our livelihood. It’s what feeds our families.”

But that income is not guaranteed.

“The prices of dye, sisal, even stall rent have shot up,” says Ann Wanjiku, another weaver in her early 30s. “Sometimes we go home with nothing. But we still come the following day.”

The women here have learned to lean on each other. They have formed chamas (savings groups) and support networks, pooling money for emergencies, school fees, and stock purchases.

Some have gone a step further, partnering with NGOs like Amsha Africa or attending trainings by the Ministry of Culture to improve their designs and learn basic business management.

Still, the road is steep.

Cheap imports from China

Wairimu explains that cheap, mass-produced imports from China have flooded the market, making it harder for local artisans to compete. Some buyers are also turning to second-hand bags from Gikomba, attracted by their trendy appearance.

“They say those bags are more stylish and very durable, but honestly, they don’t last, compared to Sisal bags,” she says.

“Why not invest in a good-quality bag that will serve you for years? And even pass them down to your children and grandchildren. You ever wonder why many grannies still have kiondos that they had 40 years ago...that is the power of sisal.”

To keep up with shifting tastes, the artisans have started blending sisal with cotton, creating softer, more versatile designs.

They have even introduced black sisal bags, a favourite among urban clients looking for something both functional and fashionable.

“People used to think sisal only comes in bright colours, but we are evolving. You can get a black woven bag that looks chic and still supports local craft,” Wairimu says.

Wairimu notes that many artisans are a little bit elderly, and they lack digital literacy, making it hard to sell their work online or attract international buyers directly.

Youngsters drifting away

Wairimu laments that the younger generation is slowly drifting away from the craft.

“Many youths today don’t want to get tired, and weaving these bags is hard work,” she says.

“But once you get used to it, everything flows. The sad part is, they just want quick money from TikTok or other easy ways, and we’re losing skilled artisans.”

Adding to the challenge, she explains, is the lack of regular platforms to showcase their work.

“Exhibitions and fairs are rare, and when they do happen, they’re mostly centred in the city. Not everyone can afford to attend, yet that’s where we’d meet buyers who value our craft.”

Despite this, Wairimu remains hopeful that with the right support, weaving can still attract a new wave of artisans, ones who see it not just as tradition, but a sustainable business.

“We’ve asked for a permanent exhibition space, where people can find us easily, not just during holidays or tourism expos. So, we have just resorted to just staying here in Kariokor,” says Mwende.

A future in fibre

Yet, despite the hurdles, optimism endures.

In a global fashion industry slowly waking up to sustainability and handmade craft, Kariokor’s weavers may have an edge, if they can scale up, brand smartly, and tap into diaspora pride.

Mwende’s daughter, now in college, is helping her mother set up a simple Instagram page. A Nairobi boutique has shown interest in placing regular orders.

“If only we had support in packaging and delivery, we’d fly,” Mwende says.

Her dream is clear: to see a “Made in Kariokor” label in stores in Nairobi, London, and beyond.

“We’re not looking for charity. We just want a chance to show the world what our hands can do.”

As the sun dips behind the tin and paper roofs of Kariokor, the last threads are knotted, the final bags dusted and hung. The women laugh, stretch, and slowly begin to pack up for the day.

But the work does not end here; it continues in their homes, in their thoughts, and in the hands that have refused to give up.

New close competition?

Just a stone’s throw away stands the newly launched Mwariro Market, a polished, multi-storey structure that some shoppers call “safe.”

Safe, however, comes at a price, while it offers improved security and cleaner stalls, traders there pay significantly higher fees for space, a cost that trickles down to customers.

“People assume Mwariro is more expensive,” Angeline, a shopper, says.

“But it depends. Some things are cheaper than here in Kariokor, but other times, Mwariro Market has better prices.”

The goods, too, are largely similar: baskets, fabric, kitchenware, but with a noticeable influx of products from Uganda, especially in Mwariro. Slowly but surely, Uganda is carving out its own market share in Nairobi’s artisan spaces.

“They have good stock,” Mwende admits, “but it’s not handmade like ours, and if you are keen, you can always tell there is a slight difference.”

So, is Mwende happy with the changes?

She pauses, then nods thoughtfully.

“Things are changing fast, some for the better, some not. But I still believe in what we do here in Kariokor. As long as there are people who value handmade work, we will survive; there is something for everyone, I believe.”

So as Mwende’s daughter continues to show her how to expand and reach her audience digitally, one thing remains: that in Kariokor, they are weaving more than just bags. They are weaving hope, identity and a future, thread by thread.

Top Stories Today