AI in African newsrooms: Can artificial intelligence help tell Africa’s story accurately and at scale?

Using the Russia–Ukraine conflict as an example, panellists showed how structured storytelling—timelines, actors, data—can “inoculate” audiences. Still, they noted, even the most accurate fact-checks rarely travel as fast or far as misinformation.

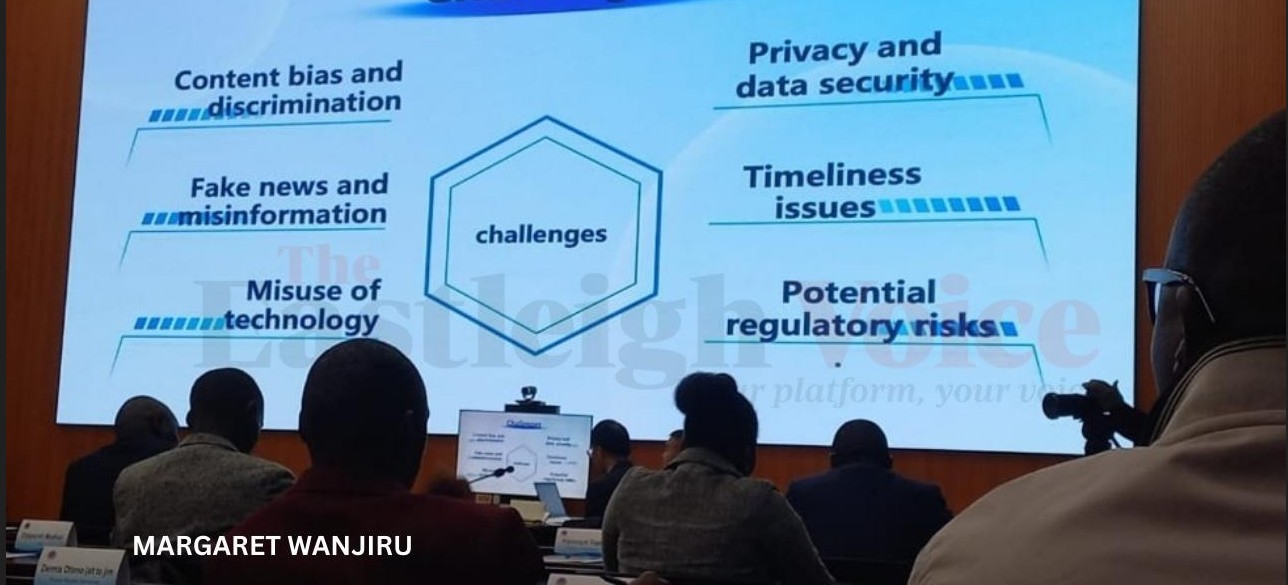

At a high-level seminar hosted this week at Xinhua News Agency’s Africa Regional Bureau in Nairobi, journalists, editors, and media scholars gathered to explore a pressing question of our time: If Chinese media is urged to “tell China’s story well,” can African newsrooms harness artificial intelligence (AI) to tell Africa’s story—accurately, ambitiously, and at scale?

The half-day event, themed “The Rise of AI in Journalism,” quickly moved beyond a technical discussion. It became a deep and urgent conversation about narrative power—how it is built, who shapes it, and how AI is reshaping the competition for attention and credibility in both local and global media.

More To Read

- AI-powered imaging technology can now detect deadly food toxins, study finds

- If AI takes most of our jobs, money as we know, it will be over. What then?

- From film to digital era: How photography in Nairobi has evolved over the decades

- How hype and Western narratives shape AI reporting in Africa, and what must change

- Kenya leads in AI innovation, policy development as Africa’s market set to triple by 2030

- Hospitals overflowing in Gaza, as malnutrition surges

A continent rich in stories, but lacking scalable systems

Speakers agreed that Africa is not short of stories. The challenge lies in speed, structure, and systems. Experts highlighted the need for infrastructure that can move stories across languages, platforms, and borders with consistency and authority.

In China, state-run outlets have already introduced AI news anchors, reflecting the country’s strong push toward automation in broadcasting.

Kenya has not reached that stage, but local newsrooms are increasingly experimenting with AI tools for translation, transcription, and content generation.

AI as an accelerant, not a threat

Li Wenfei, Deputy Director of Xinhua Africa and host of the seminar, reframed the AI debate by presenting it not as a threat to journalism but as an accelerant.

“AI can compress time through faster fact-checks, expand reach with multilingual output, and deepen context through data-driven insights, without giving away editorial control,” said Wenfei.

“Even though we have our own tools here, we still rely on human editors and journalists to make the final call. Technology supports the process, but it doesn’t replace professional judgment.”

AI cannot replace newsroom courage

Dr Chen Yingying, Associate Professor at Renmin University and former Chief Correspondent at Xinhua, joined virtually and urged participants to see narrative as a strategic asset, not just a by-product of news.

“The tool is only as brave as the newsroom,” she said, stressing that no amount of automation can fix poor editorial judgment or shallow reporting.

She explained that language remains one of Xinhua’s biggest challenges when covering Kenyan stories. Local slang, such as Sheng, often confuses AI translators, making human editors essential for nuance and accuracy.

These gaps, she noted, are being bridged through AI-assisted workflows combined with human oversight.

“AI is an assistant. It’s not here to replace us,” she added. “The fundamentals of journalism, community engagement, verification, and contextual reporting are irreplaceable.”

AI’s limits and the skills that still matter

When asked by The Eastleigh Voice whether AI threatens journalism, Dr Chen answered with calm realism: “AI can write faster, but it can’t replace your instincts, your cultural knowledge, or your ability to listen. These are the things that give stories life.”

She also pointed to the growing challenge of deepfakes and manipulated content. While the idea of attaching “proof of authenticity” to every article is noble, she admitted it may not yet be practical. Instead, she urged journalists to strengthen verification skills, from reverse image searches to building reliable chains of evidence.

She further argued that the industry should set journalism-specific benchmarks, insisting newsroom impact cannot be measured by tech-sector metrics alone.

Debunk, prebunk, and out-tell

A recurring theme was the journalist’s role in an age of misinformation. Panellists introduced the concepts of:

Debunking: disproving false information after it spreads.

Prebunking: proactively equipping audiences to recognise falsehoods before they spread.

Using the Russia–Ukraine conflict as an example, panellists showed how structured storytelling—timelines, actors, data—can “inoculate” audiences. Still, they noted, even the most accurate fact-checks rarely travel as fast or far as misinformation.

“Journalists shouldn’t believe everything they see online. In today’s media environment, misinformation can look professional, urgent, and even credible, but that doesn’t make it true,” one speaker cautioned.

They recalled a viral report claiming a Ukrainian town had been bombed: “I remember a report circulating widely that claimed a specific area in Ukraine had been bombed. Images were going viral, news alerts were already out. But something didn’t feel right. So I picked up the phone and called a trusted contact who lives there. She told me, calmly and clearly, that the area was completely safe, that not only had there been no bombing, but life was going on as normal. That moment reminded me why we must always go the extra mile to verify. In a crisis, a single call can mean the difference between amplifying fear and reporting facts.”

Standards still matter more than speed

Despite AI’s promise, panellists stressed one thing clearly: journalistic values must come first. AI can summarise, translate, and sort data—but only humans can decide what is true, fair, and worth publishing.

They warned against letting AI become a shortcut. Instead, it must serve as a force multiplier, not a crutch.

If China’s media strategy seeks narrative coherence, Africa’s strength lies in embracing plurality. With 55 countries, thousands of languages, and more than a billion people, the continent cannot be reduced to a single story.

AI may help identify regional patterns, but only journalism can capture the texture and richness of local voices.

The seminar closed with a challenge to editors and reporters: commission stories that assume global curiosity, not global condescension. And measure success not by applause at home, but by how your reporting holds up when it travels.

The tools are ready. The question is: Are we?

Top Stories Today