India's leader Narendra Modi faces a reckoning with its poor

Should Narendra Modi secure a third term as PM, one of his priorities will be improving incomes.

Exit polls in India suggest Narendra Modi's alliance will secure a third term as prime minister with a big majority. High on his to-do list will be improving incomes so that most of the country's 1.4 billion citizens are no longer poor enough to qualify for the government's free food scheme.

An overdependence on agriculture for jobs is to blame. The traditional sector employs less than one-quarter, of China's workforce. In India, some 43 per cent of workers depend on farming, but it generates only 16 per cent, of the $3.5 trillion national output.

More To Read

- Ghana and India: Narendra Modi’s visit rekindles historical ties

- Modi's party wins election in New Delhi after 27 years out of power

- India, China strike border patrol pact that could ease ties, top official says

- Narendra Modi sworn in as India prime minister for historic third term

- Indian PM Narendra Modi, allies to meet after humbling election verdict

- Modi's alliance to win big in India election, exit polls project

Farmers toil under a state-controlled system designed shortly after the country achieved independence in 1947, when food was in short supply. Today, India feeds the world as the top exporter of rice, and its role is of greater importance after Russia's invasion of Ukraine disrupted wheat supplies.

Still, India's farmers are largely poor, thanks to messy regulation, low levels of investment and inadequate infrastructure, including a shortage of cold storage. The result is that most of those who produce crops don’t have direct access to large companies or consumers, and end up with scant control over price.

A farmer walks in a corn field in Krishna district in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, India, April 1, 2024. (Photo: Almaas Masood/Reuters)

A farmer walks in a corn field in Krishna district in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, India, April 1, 2024. (Photo: Almaas Masood/Reuters)

If Modi is re-elected with a landslide, he's likely to take a second stab at shaking up farm laws, after aborting his first try in 2021. He'll do that while continuing to court big firms like Apple and Tesla to set up factories and boost manufacturing as an alternative source of employment.

His administration has set an internal target to raise rural income per capita by 50 per cent by 2030, Reuters reported in May, citing official documents. That is ambitious: farm wages grew just 0.2 per cent and rural non-farm wages fell during the 12 months to March 2023, according to Motilal Oswal Financial Services.

Hitting the goal is imperative to make India a more reliable global trading partner, however. New Delhi periodically slaps bans and duties on crop exports to protect consumers against high prices at the expense of farmers, disrupting overseas supplies of everything from sugar to wheat.

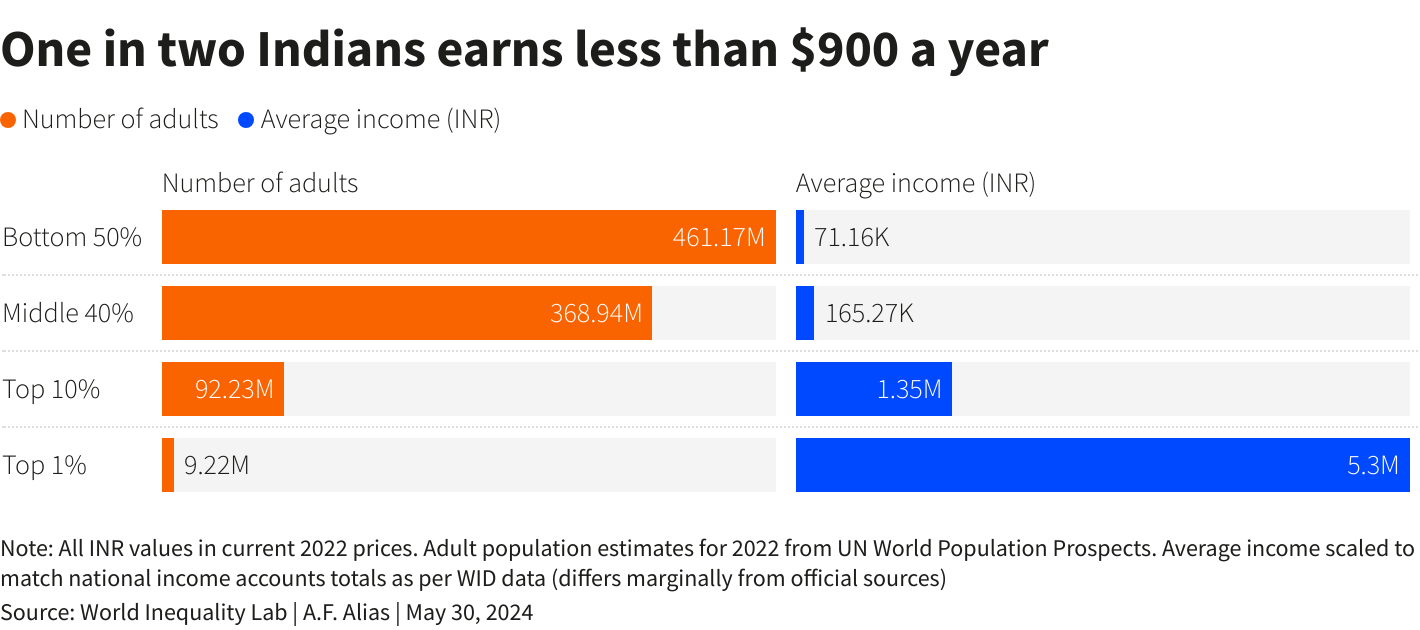

Low rural incomes translate into a huge gap between haves and have-nots and threaten social stability as global companies look to India as a hedge against China.

The top 1 per cent of people in the South Asian country earned almost 23 per cent of national income, among the highest, anywhere, according to World Inequality Lab, behind only small countries like Peru and Yemen. That's unsustainable.

Too big to fail

Any attempt to fix India's farms will require a tough stomach. Modi aborted his earlier attempt to overhaul the system after farmer groups from some northern states held a year-long protest in New Delhi.

They feared big business, including billionaires Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani would acquire farmland and worried the new laws could ultimately end generous subsidies the government pays to procure certain crops.

Inaction, though, could upend India's world-beating growth. Private consumption generates nearly three-fifths of GDP but is growing at 4 per cent year-on-year partly because the masses are getting squeezed, making the 7.8 per cent headline pace look shaky.

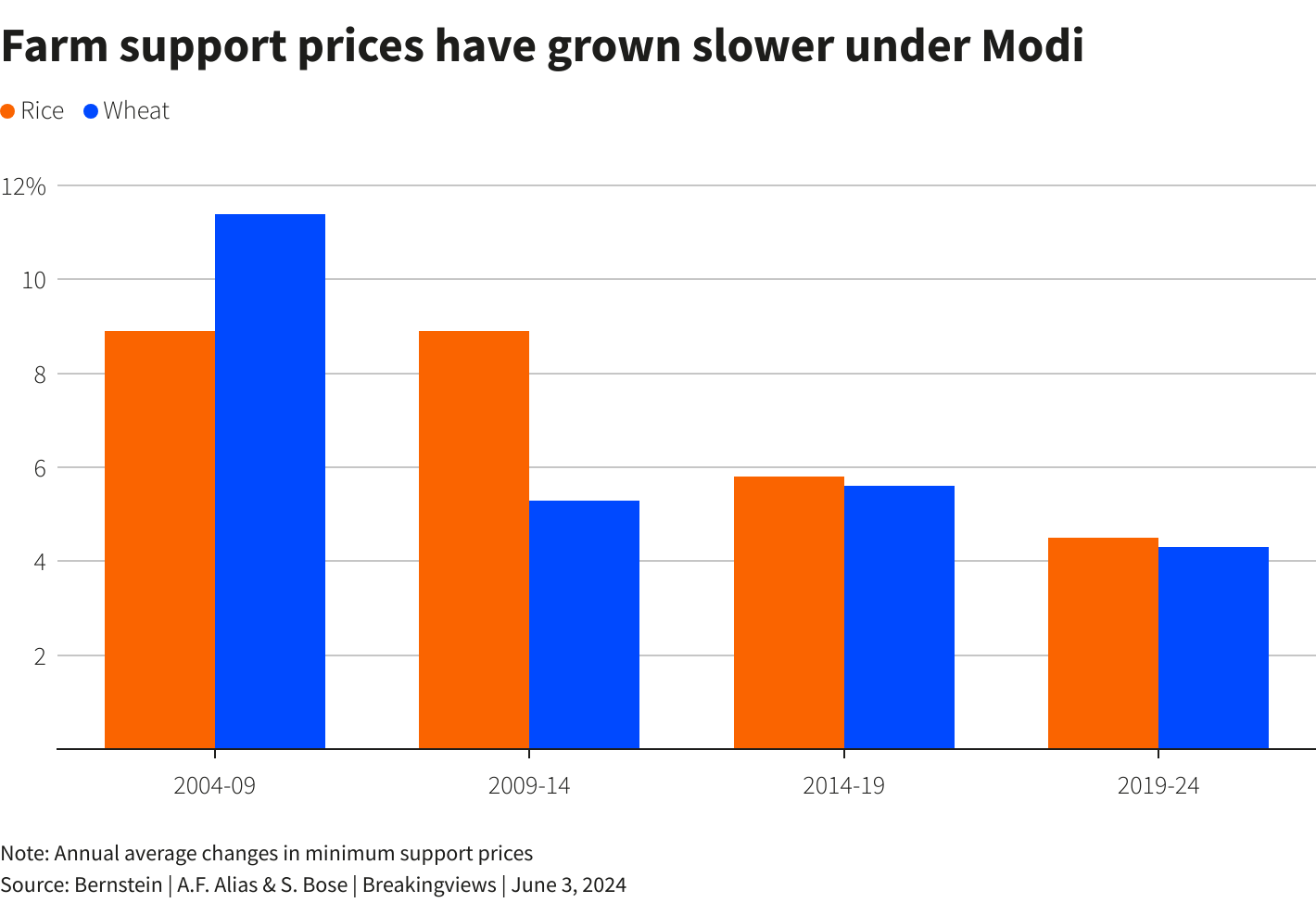

Graphic: Reuters

Graphic: Reuters

Outside the cities, consumers are cutting back on essentials like milk and cooking oil. British giant Unilever’s (ULVR.L), Indian unit has a strong presence in villages and is underperforming Nestle’s (NESN.S), local business which targets urban shoppers.

Climate change is making the situation more precarious too. Extreme weather disrupts crop cycles. Forecasting is getting tougher for rate-setters: Food remains a chunky 46 per cent of India's consumer price inflation basket.

These adverse trends could soon force India to increase handouts. As well as free food grains, farmers survive on cash transfers, subsidised fertiliser and power.

Graphic: Reuters

Graphic: Reuters

The overall subsidy bill at $50 billion, has grown at a slower pace over the last decade compared to the 10 years to 2014, per analysts at Bernstein, but it remains higher than the pre-Covid level of close to 14 per cent of total government spending.

Given Modi's struggle to push through reform, politicians are publicly tiptoeing around the problem. His Bharatiya Janata Party promises in its election manifesto to hike floor prices it pays for crops “from time to time”, for example.

Ultimately, to shore up growth, India needs to cut out the middleman. State-backed wholesale markets issue licences to buyers like Walmart (WMT.N), Amazon (AMZN.O), and ITC (ITC.NS), and charge fees on all transactions.

Buyers must have licences for every region where they source produce. Modi attempted to remove fees on sales outside of yards and to standardise direct agreements between farmers and businesses.

It would be a shot in the arm for farmers and a crucial step towards fixing the income gap. A strong, confident leader will recognise that India’s rural population is simply too big to fail

Top Stories Today

- Nairobi Speaker throws out Sakaja ouster petitions over legal gaps

- Businessman Obure claims life in danger after winning Sh1.3 billion property dispute

- Major city roads to be shut on Sunday for CHAN tournament

- Egerton VC faces sanctions as Parliament tightens grip on mismanaged institutions

- Government evacuates 5,232 distressed Kenyans from 19 countries

- Audit uncovers illegally appointed NCIC commissioners still drawing full salaries