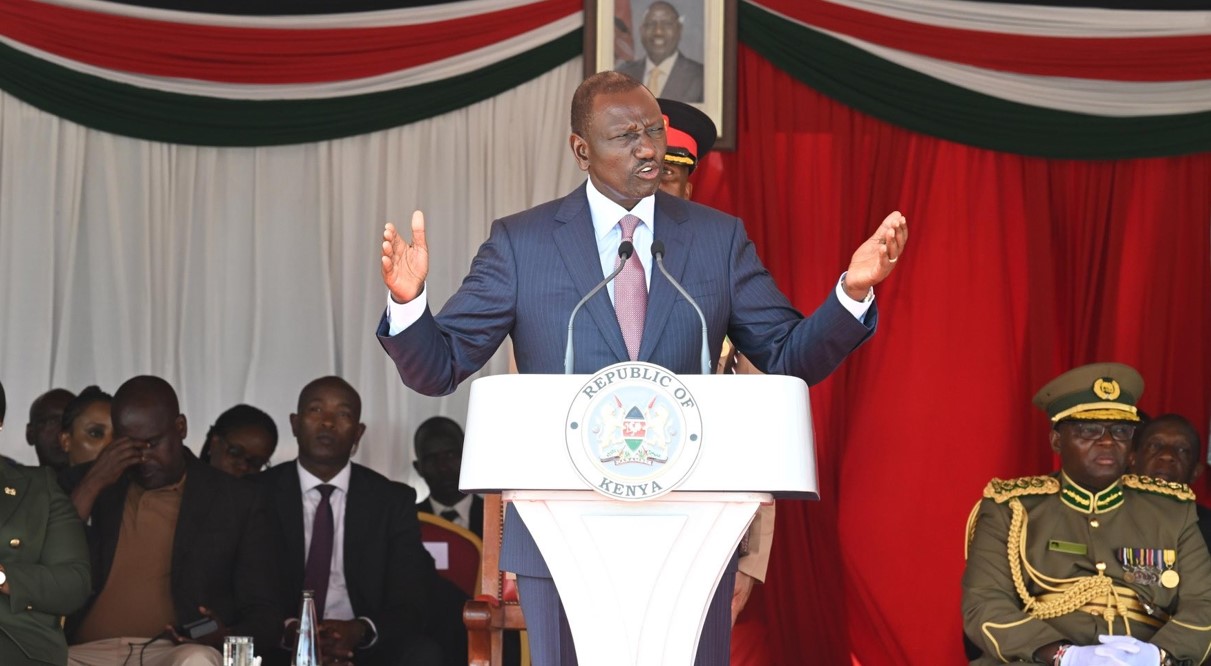

How Kenyan-born Bahraini steeplechase champion Winfred Yavi eluded the country’s grasp and lessons Kenya can learn from her success

Winfred Mutile Yavi, originally from Kenya and now representing Bahrain, claimed gold in the women’s 3,000 metres steeplechase at the Paris 2024 Olympics, setting a new competition record. Her switch to Bahrain has sparked renewed discussions following her recent success.

Bahraini athlete Winfred Mutile Yavi stunned the world on the night of August 6, 2024, at the Stade de France in Saint-Denis, Paris, when she won the women’s 3,000 metres steeplechase at the 2024 Paris Olympic Games with a competition record time of 8:52.76, breaking the previous Olympic record of 8:58.81 set by Russia’s Gulnara Samitova-Galkina at the 2008 Beijing Olympics by more than six seconds.

Yavi, who is also the reigning world champion in the event following her victory at the 2023 World Athletics Championships in Budapest, Hungary, ran a tactical race. She conserved her energy prudently, preparing herself to unleash a devastating kick in the final stretch of the race.

More To Read

As the duo of Kenya’s Beatrice Chepkoech, the event’s world record holder, and Uganda’s Peruth Chemutai, the previous Olympic champion, took it upon themselves to control the race's pace by leading for most of it, Yavi, never appearing as a threat, stalked them with the innocence and naivety of a greenhorn while concealing her intentions with the detached aura of a seasoned assassin.

When the bell went off for the final lap, Yavi had already done enough surveillance. Her simultaneous injection of pace into the race, alongside Chemutai, created a gap between her and the Kenyan duo of Faith Cherotich and Beatrice Chepkoech, as well as the Ethiopian Sembo Almayew.

The five athletes had formed a dominant leading pack, but after the bell, they began to split up, with Chemutai and Yavi breaking away as the rest aligned in single file in a frantic chase for glory.

Yavi ran side by side with Chemutai, never letting the Ugandan slip away, and at the last hurdle, she isolated herself from the then-Olympic champion with a burst of pace that left the subdued Ugandan in despair and disbelief. Yavi then crossed the finish line, jubilantly raising her hands in the balmy Parisian night under a cacophony of applause from the cheering crowd. This historic moment garlanded her with a gold medal and crowned her an Olympic champion with a competition record in the event.

A dejected Chemutai, the ousted Olympic champion, finished second with a time of 8:53.34. Kenya’s best performer in the race, Faith Cherotich, took the bronze medal after finishing the race with the determination of a patriot keen on ensuring the country secured a place on the medal podium in the event for the sixth consecutive Olympic Games. Cherotich’s time of 8:55.15 was a personal best.

Beatrice Chepkoech, one of the pre-race favourites, finished a disappointing sixth with a time of 9:04.24, a performance indicative that the race came too soon for her as she was still recovering from pneumonia.

Chemutai was not the only dejected soul on that Tuesday night, as Kenyans struggled to understand how Winfred Mutile Yavi, born in Makueni County, Kenya, on December 31, 1999, slipped the grasp of those responsible for ensuring the country has a consistent pipeline of world-conquering athletes. Yavi fits that profile, but she now runs for Bahrain, where she even serves in the Asian nation’s defence forces.

Kenyans, donning their speculation caps, offered a myriad of reasons as to why Yavi ended up representing the Persian Gulf nation instead of her motherland. The reasons given laid the blame on corrupt and unethical practices that bedevil almost every sector of Kenyan socioeconomic and political life.

There were even quotes from Yavi that Kenyans used as references to support their assertions on what made the 24-year-old opt to compete for Bahrain instead of her country of birth.

The quotes by Yavi come from an interview she did with SPM Buzz last year at JKIA upon arriving in the country following her World Athletics Championships victory in Budapest.

"I didn't get the opportunity to represent Kenya," says the Women's 3000m Steeplechase Paris Olympic gold medalist, Winfred Mutile Yavi explaining her decision to run for Bahrain instead of Kenya. #Olympics pic.twitter.com/M98cSOXFEX

— Ole Teya (@TeyaKevin) August 6, 2024

In that interview, Yavi attributed her decision to run for Bahrain to her consistent failure to get opportunities to represent Kenya in international races.

“Competition in Kenya was quite stiff. I never got a chance to join the Kenya team because I used to finish outside the qualification slots during trials. I never qualified despite being ready to represent my country,” Yavi said.

In the interview, which has gone viral, Yavi said her decision to change allegiance was informed by her failure to make the Kenya team for the 2016 IAAF World U20 Championships, which were held in Bydgoszcz, Poland.

“On that occasion, there were only two slots for qualifying for that championship, but I finished third despite working so hard to get a slot,” Yavi told her interviewer.

Indeed, at the 2016 IAAF World U20 Championships, Kenya was only represented in the women’s 3,000 metres steeplechase by Celliphine Chepteek Chespol and Betty Chepkemoi Kibet, a clear indication that Yavi, then only 16 years old, had failed to make the cut.

Chespol went on to justify her inclusion in the team by winning the gold medal at that tournament with a championship record time of 9:25.15. Kibet was fourth after clocking 9:38.27.

Interestingly, Bahrain had an Ethiopian-born athlete, Tigist Getnet, in that race, who scooped silver with a time of 9:34.08. However, she has never been heard of again since, with her career not living up to her early promise.

That tournament ran from July 19 to July 24, 2016, but less than one month after the end of that tournament, on August 19, 2016, Yavi had already been granted eligibility by the IAAF, now World Athletics, to compete for Bahrain, with the decision approving her change of allegiance having been made between April 25, 2016, and June 29, 2016.

At this juncture, it is necessary to explore the circumstances that contributed to Yavi changing her allegiance at the age of 16, when she was just an unknown prodigy with many years of opportunities ahead of her to make her mark while representing Kenya.

The journey in search of that answer takes us back to the early 2000s, when Qatar, Bahrain’s maritime neighbour in the Persian Gulf, began an aggressive campaign to transform the tiny Asian nation into a sports powerhouse and, as a result, improve its image internationally.

In Simon Kuper’s Soccernomics, an illuminating book that explains why some nations perform better at football than others, the Ugandan-born Dutch author states that for a nation to dominate any sport, it needs to have two of the following three things: a huge population to produce the requisite sporting talent in great numbers, a thriving economy to support the development of sporting activities and infrastructure, and a robust network with other countries in the sport they seek to dominate so as to facilitate knowledge transfer.

In Qatar’s case, and Bahrain’s too, they were only doing well on one criterion – they had a thriving economy, which made them capable of financing the development of sporting activities and infrastructure to the tune of millions of dollars.

However, their population is small and struggles to produce enough sporting talent among its indigenous citizens.

For context, as of 2022, Qatar's population was 2.6 million, with only 313,000 (12% of the total population) being indigenous Qataris.

In Bahrain’s case, their population in 2022 stood at 1.5 million, with only 712,000 of those people being indigenous Bahrainis (47% of the total population).

Therefore, already outnumbered in their own country by foreigners, Bahrain and Qatar hardly have the numbers, on their own, to produce a legion of athletes who can dominate the world in various sports.

In terms of networking, Bahrain and Qatar are isolated from dominant sporting nations by their geographical location, because their neighbours in the Gulf are not that good in sports either. Hence, in terms of knowledge transfer, they cannot gain substantially from interacting with their neighbours on sports matters.

As such, to bridge the gap, using their vast financial resources, it made sense for the two countries to import foreigners with requisite expertise and knowledge to set up robust sporting structures and systems and, most importantly, give citizenship to talented athletes from dominant sporting nations to integrate into those structures and systems. In a way, they were killing two birds with one stone.

Qatar was ahead of Bahrain in doing this, and in the early 2000s, they started giving citizenship to talented athletes from Kenya, Ethiopia, and other countries that had a surplus of talent in sports.

Kenyans can famously remember in the early 2000s that Qatar offered Dennis Oliech, perhaps the greatest footballer the nation has ever produced, a reported Shs 200 million to change his citizenship and represent Qatar in international competitions.

Thrs a time Dennis Oliech was offered money to change his citizenship and play for Qatar, Kenyans were up in arms na tulimkashif sana! I think we owe him an apology, we gave him a wrong advice.

— Daddy Owen (@daddyowenmusic) April 28, 2024

However, even if Oliech had accepted the offer, it would have been impossible for him to play for Qatar, as he had already featured for Kenya in high-level international matches, including the 2004 African Cup of Nations.

In the same year, Qatar still showed its determination to assemble an all-star team of talented footballers not capped internationally by their countries. In March 2004, the Qatar Football Association tried to incentivise the Brazilian Ailton to play for their national team.

At the time, despite lighting up the Bundesliga with Werder Bremen, Ailton had not been capped internationally by the South American nation, and the Qataris offered him 1 million euros (then equal to Shs 94 million) to change his citizenship on top of paying him an annual salary of 400,000 euros (the equivalent of Shs S 37 million at the time) for his services to the national team.

If successful, Ailton, who had scored 28 goals that season and helped Bremen win the Bundesliga and the DFB-Pokal, would have been the first non-naturalised player to play for the Qatar national football team. However, FIFA stopped the deal as the international governing body of association football revised its rules in a bid to preserve the integrity of the game.

Ailton was gutted by the decision, which saw him miss out on the opportunity to represent Qatar at the 2006 FIFA World Cup, and even threatened to challenge FIFA’s decision in court. However, the Qatari football authorities assured him that they would pay him the 1 million euros promised even though he wouldn’t feature for them.

Despite the failure of this ambitious move by Qatar, the nation's authorities did not lose hope. Instead, they shifted their focus to athletics, where they knew they could get naturalised athletes to compete for them without breaking any rules.

The most famous athlete to switch allegiance to Qatar is Stephen Cherono, who was a talented athlete in Kenya’s junior athletics ranks in the early 2000s. His talent and potential, especially in the 3,000 metres steeplechase, caught the attention of the Qatar Athletics Federation, which saw him as the right athlete to put them on the global athletics map.

Stephen Cherono (Saif Saaeed Shaheen) 693 brother to Abraham Cherono 692 representing Qatar was a painful one because he was so good. Man is earning 1000 USD every month and he retired ages ago. If only Oliech had taken the Qatar deal as well. All the best to Yavi. pic.twitter.com/ABiZEwhhIN

— Hillary (@korirHilla) August 7, 2024

After undergoing a name change to Saif Saaeed Shaheen, Cherono switched allegiance to Qatar. He won gold medals for the nation at the 2003 World Athletics Championships in Paris and the 2005 World Athletics Championships in Helsinki in the 3,000 metres steeplechase.

Shaheen would have also competed for Qatar at Athens 2004, but IOC eligibility rules prevented him from doing so, as he needed to have competed for Qatar for at least three years before that edition of the Olympic Games.

However, Qatar's ability to negotiate an opportunity to compete at those games for him shows the lengths to which they were willing to go to justify the investment in their naturalised athletes.

As Qatar continued to make its mark on global athletics with Kenyan-born athletes, Bahrain arrived a bit late to the party with its bronze medals – won by former Kenyans – in the men’s 1,500 metres and men’s 10,000 metres at the 2006 World Junior Athletics Championships.

From that point, Bahrain made their intentions known by giving citizenship to athletes with the potential to win them medals at global athletics tournaments.

These athletes came from Kenya, Ethiopia, and Morocco, and with the success that they brought to Bahrain, more and more athletes from these three countries, who would have otherwise found it difficult to qualify for their national teams, went to Bahrain and accepted citizenship to pursue their sporting dreams.

Winfred Mutile Yavi is a product of that system. This means that Kenya has only itself to blame for letting her go and must put in place measures to ensure the best athletes born in Kenya represent the nation at global sporting events.

This is a better approach than Kenyans merely venting on social media when athletes such as Yavi leave Kenya and conquer the world for other countries.