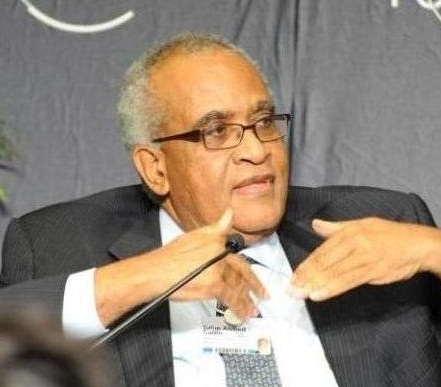

Salim Ahmed Salim: African diplomat who almost led United Nations

Salim was, arguably, the closest Africa has come to clinching the UN’s top job. His age, diplomatic poise, and Pan-Africanist ethos made him a standout.

More than four decades after Dr Salim Ahmed Salim’s near-ascent to the highest diplomatic office in the world, declassified notes dated August 5, 1980—released by the Salim Ahmed Salim Digital Archive in Dar es Salaam—offer a gripping behind-the-scenes look into a campaign shaped by Cold War intrigue, bloc politics, and missed opportunity.

Then aged just 39, Dr Salim—a former President of the UN General Assembly and Tanzania’s Permanent Representative in New York—had emerged as a credible Third World candidate for Secretary-General of the United Nations.

More To Read

- UN warns Kenyans over spike in scams linked to staff relocation to Nairobi

- Over one billion Africans unable to afford healthy diet, UN report warns

- UN sounds alarm over Nairobi’s mounting garbage crisis

- UN report: Gains in ending FGM at risk unless Kenya scales up action

- UNESCO urges dialogue as world marks day for remembrance of slave trade, abolition

- World marks UN day honouring victims of religion-based violence

A rising tide of African and Non-Aligned Movement support was behind him.

But as documents seen by Eastleigh Voice reveal, geopolitical undercurrents would ultimately capsize what many pundits still consider the most formidable African candidacy for the role.

At a private dinner at Havana’s iconic Bodeguita del Medio, Cuban Foreign Minister Isidoro Malmierca publicly committed to Salim’s candidacy with a flourish.

Scrawled on the restaurant wall—a tradition among international visitors—was a bold inscription: “Aquí estuvo el próximo Secretario General de la O.N.U., Salim Ahmed Salim – 9/viii/80” (“Here was the next Secretary-General of the UN, Salim Ahmed Salim”).

That endorsement, while symbolic, captured the spirit of the Global South’s campaign.

During a prior meeting, Cuban Vice-Minister Ricardo Alarcón, a veteran of UN diplomacy himself, offered an unfiltered view: “There is no personality in the Third World at the moment with your credentials and recognition. If there was to be a Third World nominee, you had the best prospects.”

But geopolitics is rarely driven by merit alone.

Washington viewed Salim with suspicion for his anti-apartheid stance, support for Palestinian self-determination, and close ties to revolutionary Cuba and China.

Moscow, on the other hand, was wary of Salim’s perceived leanings towards Beijing—a cardinal sin in Cold War arithmetic at the time.

The deadlock lasted six weeks, with 16 rounds of voting. Eventually, both candidates withdrew, paving the way for a compromise choice.

As Salim later wrote in his note: “It is common knowledge that the Soviet Union and the United States are very crucial... They are always unguarded, and invariably they make their decision at the last moment.”

When voting began, Salim actually led the first round—11 votes to incumbent Kurt Waldheim’s 10.

But both he and Waldheim faced vetoes: the US blocked Salim; China blocked Waldheim. After 16 rounds and six weeks of stalemate, both candidates stepped aside.

Salim was, arguably, the closest Africa has come to clinching the UN’s top job. His age, diplomatic poise, and Pan-Africanist ethos made him a standout.

And here’s a fun fact—Salim was just 39 years old when he vied for the role, making him one of the youngest candidates for UN Secretary-General ever.

His diplomatic career began even earlier—at just 19, he was posted as Deputy Chief Representative of the Zanzibar Office in Havana, Cuba.

But in the zero-sum game of Cold War diplomacy, even Africa’s best wasn’t enough.

Today, the declassified notes do not merely mark a moment lost—they serve as a reminder of what might have been.

Salim, ever the diplomat, concluded in his reflection: “The Secretary-General is the representative of all nations and all groups. Yet the support of Africa and the Third World is vital.”

Top Stories Today