On the Margins: Street families highlight challenges in accessing healthcare

In response to these pressing issues, various organizations advocating for street individuals' rights convened a training program targeting service providers.

More To Read

- Ministry of Health cracks down on bed sharing in public hospitals, labels it fraud

- KNH issues strict SHA admission guidelines to combat billing fraud

- How far is your closest hospital or clinic? Public health researchers explain why Africa needs up-to-date health facility databases

- New push to rehabilitate street families as population census begins June 29

- New Bill proposes Sh50 million for health providers over neglect and unsafe facility conditions

- Kenya boosts medical interns' support with Sh4.3bn allocation in 2025/26 health budget

Street families confront a myriad of obstacles, with healthcare access emerging as a paramount yet overlooked challenge.

The individuals claim they face pervasive discrimination and neglect in healthcare settings, exacerbating their already dire circumstances.

This is even the government plans to include them in the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) programme. In the programme, low-income earners will contribute as little as Sh300 a month, while the government will pay for those who are unable.

Primarily, homeless individuals grapple with inconsistent access to healthcare facilities due to their lack of stable residence and transportation. Hindered by these obstacles, they often struggle to reach clinics or hospitals regularly, if at all, depriving them of timely medical attention.

Kevin Mwangi, a homeless victim, says that even when seeking medical assistance, they frequently encounter discrimination and stigma. He recounts being chased away from healthcare facilities.

Samson Gitau, another homeless person, says that rather than receiving comprehensive care, they are often merely provided with medications without addressing their broader healthcare needs.

"The healthcare workers don't examine you as is expected. They just give you some medicines and tell you to go," Samson says.

Moreover, the street families also claim mental healthcare remains severely neglected, despite the exacerbating impact of homelessness on mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, and PTSD. They say access to mental health services is often inadequate or inaccessible.

People with disabilities on the streets also claim to face challenges, navigating physical limitations alongside the harsh realities of street life. Geoffrey Kariuki, paralyzed on one leg, describes the struggle for treatment amidst dependency on mutual support networks.

"For countless years, I've been trapped in this situation, unable to access any form of treatment. Each day, I find myself sinking deeper into depression and hopelessness. I rely on the meagre support of friends, as I'm unable to venture out to seek food or employment. Life has shown me no mercy, and with each passing day, it seems to only grow harsher. My health continues to decline, hindered by the obstacles preventing me from obtaining health insurance and financial aid," he says.

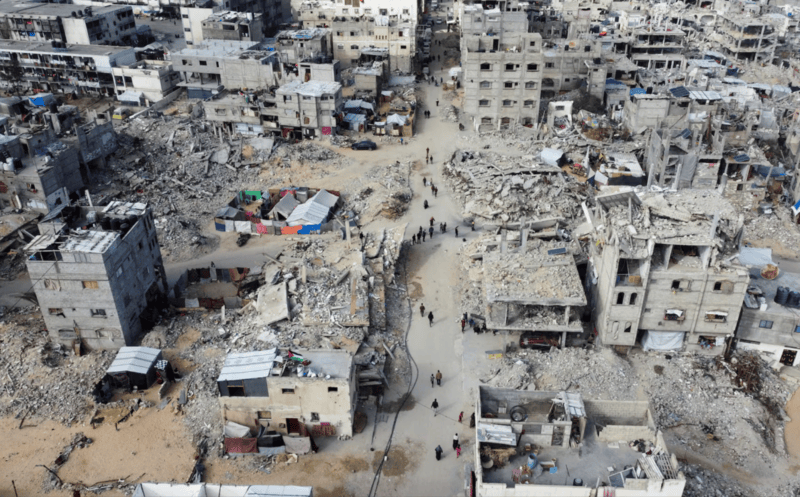

A selected cohort of community health workers, paralegals, and youth leaders during health care rights for people living on the streets training at the KCITI Eastleigh campus on March 15, 2024. (Photo: Justine Ondieki).

A selected cohort of community health workers, paralegals, and youth leaders during health care rights for people living on the streets training at the KCITI Eastleigh campus on March 15, 2024. (Photo: Justine Ondieki).

In response to these pressing issues, various organizations advocating for street individuals' rights convened a training program targeting service providers.

Held in Eastleigh on March 15, the program aimed to equip community health workers, youth groups, and nurses with knowledge on ensuring equitable healthcare access without discrimination.

The trainees focused on slum areas including Kariobangi, Dandora, Kayole, Mathare, and Eastleigh. The training aimed to empower participants to advocate for policy-level changes and implement measures to serve street families better.

Undugu Society partnered with the county government of Nairobi to offer training to various service providers.

Linet Olando, an advocate for the health rights of street families and project officer for Undugu Society, said they started the project after realizing the plight of the street families.

“We started this training and project after conducting research and realizing that the street-connected families have been neglected, especially their health, discriminated against when they visit the facilities, and they don’t get the services they deserve,” she said.

Caleb Ngala, a youth representative in Mathare, said they are advocating for the rights of the street families.

“We advocate for the rights of the street family because they are the most marginalized group out there, and we came to speak on behalf of them. As we are speaking, we have managed to make health care services accessible to some in facilities such as Mathare National and Referral Hospital. They get free counseling sessions," he said.

During the training, healthcare providers claimed the transient nature of homelessness further complicates continuity of care, with individuals frequently losing access to follow-up treatment upon relocating.

This hampers efforts to manage chronic conditions and prevent relapses, underscoring the urgent need for equitable healthcare access for street people as both a matter of social justice and a public health imperative.

Top Stories Today