UN working group offers hope to families of victims of enforced disappearances

In Kenya, enforced disappearances have happened in the past, mainly in the context of counter-terrorism operations

For Kenyans whose loved ones went missing at the height of the Gen Z protests, finding them after their searches failed to yield fruit may appear far-fetched, especially now that security agencies have adopted a lacklustre approach to addressing the matter.

Most families are afraid of reporting to the police about their missing relatives since they fear becoming victims too.

More To Read

- Five Gen Z protest-related cases closed, others still under review - ODPP

- Amnesty International calls for accountability, transparency in KDF's role during Gen Z protests

- ODPP presses IPOA to fast-track probe into Gen Z protest killings after BBC documentary

- How Gen Z used caricatures, humour to criticise government officials

- Ruto expected to attend Kagame swearing in ceremony in Kigali

But all is not lost.

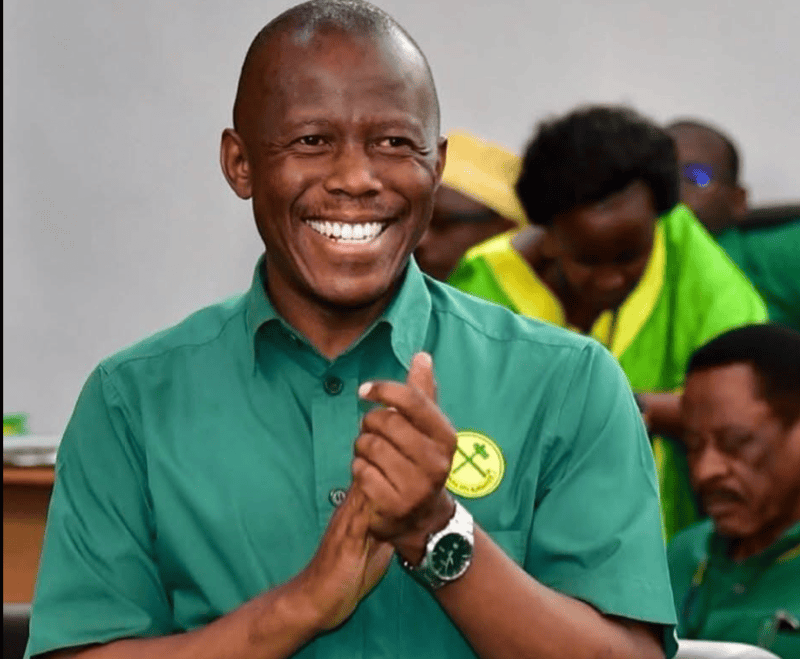

According to Ms Aua Baldè, the chairperson of the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, they can still file a case with the group and eventually find their loved ones.

"You do not have to have standard evidence of the case as required by a court. The details of the person and the consent of the family are enough," Baldè told The Eastleigh Voice.

Anyone in the category of human rights defenders, victims, lawyers or someone assisting victims of enforced disappearances can file an urgent appeal with the working group.

Cases that are received by the secretariat within three months of happening are treated as urgent as the likelihood of the missing person being found alive is high.

“Once we receive such cases, we transmit the request to the respective governments asking them to clarify the fate of the disappeared persons. We also provide a platform for the victims to tell us about their violations,” she said.

For persons who have been missing for more than three months, a standard case can also be filed. All that is required in both instances is consent from the victims or families.

The working group then notifies sources that urgent action has been sent to the state concerned, thus helping relatives or the source to enter into communication with the relevant authorities.

Article 2 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICCPED) defines enforced disappearance as “the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the state or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorisation, support or acquiescence of the state, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law”.

However, Kenya has yet to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance which came into force in 2010.

“I encourage you to send us cases and general allegation letters and seek to speak with us during our sessions. Our mandate does not require the government to ratify the convention; we work around the world with victims from different countries and we stand to do the same for the victims of enforced disappearances in Kenya,” Baldè said.

During her visit, Baldè noted that enforced disappearance is a complex and unique crime that lasts from the moment the individual disappears until the fate of the person is established.

The family of the missing person must show that the state refuses to acknowledge it has him or her in custody and as a result, the person is placed outside the protection of the law.

In Kenya, cases of enforced disappearance have happened in the past, mainly in the context of counter-terrorism operations.

The Gen Z protests brought back the dreaded disappearances, with persons suspected to be behind the protests getting abducted by masked police officers in broad daylight, much to the chagrin of Kenyans. The Law Society of

Kenya obtained orders seeking to stop the abductions but the police remained unfazed. The abductions continued even as some security agencies insisted on referring to them as arrests.

“I would like to speak about the phenomena of short-term enforced disappearances that you have witnessed here in Kenya in the last few weeks. Short-term disappearances are still disappearances except that the individual is being held for a limited period,” said Baldè.

With over 60 individuals missing from the protests according to data from the Kenya National Human Rights Commission (KNHRC), shaken families with an idea of how their kin went missing can reach out to the working group for help in tracing them.

According to the working group, most of the victims of enforced disappearances are men who are also their families' breadwinners.

Baldè said most victims that she has worked with have told horrific stories of suffering and how the disappearance of their loved ones impacted their lives, including women whose husbands have disappeared and have suddenly been placed into the role of not only taking care of their families and children but also looking for their loved ones.

“Many also tell me that it’s very difficult to obtain justice for their violations and they don’t know where to turn to report disappearance and seek information. This is where the working group comes in,” she added.

The UN working group operates on a humanitarian mandate to assist families in determining the fate and whereabouts of their relatives who have reportedly disappeared. Its role ends when the victim has been found.

Top Stories Today