Vaccine hesitancy: Inside Kenya’s push against measles, rubella and typhoid

Hidaya, a community health promoter based in Nairobi, acknowledges the concerns being raised, particularly regarding the rubella vaccine. She notes that while the overall reception to the campaign has been positive in many areas, there is still resistance among some parents.

Amos Kaimenyi, a father of a three-year-old living in Pumwani, has chosen not to vaccinate his child during the current government-led campaign targeting measles, rubella, and typhoid.

His concerns stem primarily from a lack of clear information and deep skepticism.

More To Read

- Understanding the gaps: Why HPV vaccine uptake in Kenya remains worryingly low

- Africa: A tentative start in mass vaccine production

- Kamukunji faces vaccine crisis as over 12,000 children miss routine immunisation

- Mpox outbreak: What you need to know to stay safe

- Rising mpox cases, cholera outbreaks and HIV misinformation straining Kenya's public health sector- report

- 314 mpox cases confirmed as MoH ramps up containment across 22 counties

“I’ve always known that children receive the measles vaccine at nine months,” Kaimenyi says. “Now they’re coming to vaccinate children up to 14 or 15 years old, and no one has explained why. What’s changed?”

For Kaimenyi, the typhoid vaccine is especially puzzling. He believes typhoid can be prevented through basic hygiene—keeping food and water clean, avoiding dirt, and living in sanitary conditions. “Why suddenly push a vaccine for something we’ve been told we can prevent ourselves?” he questions.

His doubts are further amplified by fears about the vaccine’s safety. “As far as I know, the body builds its immunity naturally. I’ve never heard of people getting vaccinated for typhoid before,” he says. “If my child falls ill after this vaccine—gets a fever, or worse, what if they lose the use of their hand—who takes responsibility? No one is talking about that.”

Kaimenyi also highlights the lack of consent and information within the community. Several neighbors, he says, have complained that their children were vaccinated in school without parental knowledge or approval.

“Some parents only found out after their children came home with a vaccination card. No one explained what had been done.”

Amos Kaimenyi. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Amos Kaimenyi. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

In search of answers, Kaimenyi visited his local health facility. Instead of clarity, he was met with more confusion. “Even the healthcare workers didn’t seem to know much about the vaccination drive. They couldn’t answer my questions.”

To make matters worse, he says he was told the typhoid vaccine wasn’t even available at the local hospital. “If the vaccine isn’t even on the ground, how is it being administered in schools?”

His concerns go beyond side effects. Kaimenyi believes the entire process lacks accountability and risks long-term consequences. “If my child gets sick, I’ll have to pay for treatment. Nothing is free—not outpatient services, not medicines. Only admitted patients get help. So, who takes responsibility when things go wrong?”

Despite acknowledging he might not have all the facts, Kaimenyi remains firm in his decision. “If the vaccines are truly safe and effective, then that’s good for the parents who have chosen to vaccinate. As for me, I prefer prevention. My child was vaccinated for measles at nine months, and I believe that was enough.”

He urges the government to take the matter seriously, especially when dealing with concerns about vaccine safety. “We’ve heard cases of children feeling numb or experiencing paralysis after vaccines. If a child’s hand becomes permanently damaged, how will the government support that family? Why are we only given a card and nothing else—no explanation, no follow-up?”

He adds, “Some of the people administering these vaccines aren’t even properly trained. They just show up and inject children, often without parental consent. That’s not acceptable.”

On the other hand, Pauline Muonja, a mother of three from Eastleigh, shares a different perspective. Her children—aged 14, 7, and 5—were vaccinated at school and came home with cards showing they had received the measles, rubella, and typhoid vaccines. While she wasn’t consulted beforehand, she isn’t worried.

“I wasn’t asked, but I believe it’s for their good,” Muonja says. “The vaccines will protect them. That’s what matters.”

Pauline Muonja. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Pauline Muonja. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

She encourages other parents to trust the vaccination process. “My advice is simple: let your children be vaccinated. These vaccines are meant to protect, not harm.”

However, not all parents share Muonja’s trust. Maureen Wanjiku, another concerned mother, says she won’t allow her two-year-old to receive the vaccine, at least not yet.

“I’ve never heard of anyone getting vaccinated for typhoid before,” Wanjiku explains. “Even in my wider circle, no one knows about it. It feels like an experiment. I’ll wait until I get more information.”

Hidaya, a community health promoter based in Nairobi, acknowledges the concerns being raised, particularly regarding the rubella vaccine. She notes that while the overall reception to the campaign has been positive in many areas, there is still resistance among some parents.

“The uptake for measles and typhoid has been encouraging,” she says. “But when it comes to rubella, we’re seeing a lot of hesitation. Many parents are refusing it simply because they don’t understand what it’s for.”

Hidaya also shares her own experience as a parent, noting that her child was vaccinated at school. However, she emphasizes that there was a clear communication process in place in her case.

“Messages were sent to parents beforehand asking them to either give consent or decline. I received the message, and I agreed to it because I understand the importance of vaccination,” she explains.

Kenya’s Ministry of Health launched a 10-day national immunization campaign from July 5 to 14, 2025, aimed at protecting children from two major health threats: measles-rubella (MR) and drug-resistant typhoid. The campaign targets children across the country and forms part of the government’s broader efforts to reduce vaccine-preventable illnesses and strengthen child health nationwide.

Children aged 9 to 59 months are receiving the MR vaccine, while those aged 9 months to 14 years are being given the Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine (TCV). The Ministry has set ambitious targets of 95% coverage for MR and 80% for TCV.

According to the Ministry, the campaign has already made significant progress, with approximately 3.5 million children vaccinated against measles and 12 million against typhoid as of mid-July.

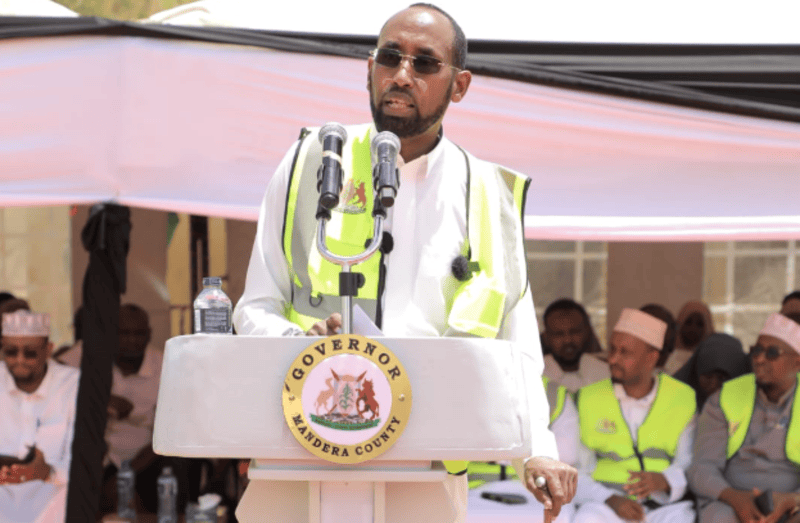

Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale, who launched the campaign, stressed that no child should be left behind.

“Our goal is clear — 95 per cent MR coverage and 80 per cent TCV coverage,” Duale said. “No child should suffer or die from preventable diseases.”

Duale warned of the growing threat of antimicrobial-resistant typhoid, which disproportionately affects children under 15. Those under five are at the greatest risk of severe complications or death. He noted that climate change and rapid urbanization are worsening conditions that allow typhoid to spread, especially in densely populated areas with poor sanitation.

The campaign also comes amid a resurgence of measles, with outbreaks reported in 18 counties. Between January 2024 and February 2025, health authorities recorded 2,949 measles cases and 18 deaths. Duale emphasized that poor uptake of the second MR dose—typically given at 18 months—has left many children unprotected and at risk.

He urged parents and communities to participate actively in the campaign.

After the campaign, the Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine will be added to Kenya’s routine immunization schedule, administered at nine months alongside other essential childhood vaccines.

While vaccine hesitancy is a challenge faced worldwide, a recent spot check in Kenya revealed a significant lack of awareness and education about the current immunization campaign. Many parents and caregivers remain unclear about the reasons behind the vaccination drive and whether there is an ongoing outbreak of typhoid or measles. This uncertainty contributes to reluctance in accepting vaccines.

It is important to note that neither the typhoid nor the measles-rubella vaccines are new. The Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine (TCV) was approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017 after extensive clinical trials demonstrated its safety and effectiveness. The vaccine is specifically designed to protect against typhoid fever, a serious bacterial infection spread through contaminated food and water. Children aged 9 months to 15 years are eligible for TCV, as they are the most vulnerable to typhoid infection and its complications.

The measles-rubella (MR) vaccine has been widely used for many years and is included in routine childhood immunization schedules worldwide. It protects against measles—a highly contagious viral disease that can cause severe complications—and rubella, which poses serious risks to pregnant women as it can cause birth defects. The MR vaccine is typically administered to children between 9 and 59 months during campaigns and routine immunizations.

Both vaccines have undergone rigorous testing and have been proven safe and effective by the WHO and other global health authorities.

Top Stories Today