The silent threat: Why Kenyan men avoid prostate cancer screening

Prostate cancer is a disease in which abnormal cells grow in the prostate, a small gland in men that helps produce semen. It is one of the most common cancers in men, especially as they get older.

As Tingidi Murane approaches 40, the age when prostate cancer screening is recommended, he struggles with the idea of seeking medical attention for something he has never even considered.

To him, the thought of undergoing such an examination feels unnecessary—if not outright uncomfortable. "Why should I go to the hospital for my manhood to be examined when it’s functioning well?" he wonders.

More To Read

- Africa’s hidden stillbirth crisis: New report exposes major policy and data gaps

- Born too soon: The hidden burden of preterm birth, fight for survival

- KUTRRH introduces groundbreaking nuclear therapy for advanced prostate cancer

- Governors decry Health Ministry’s move to deny maternity funds to dispensaries

- MPs pass historic Bill regulating fertility treatments and surrogacy

- Ministry of Health announces measures to reduce maternal, newborn deaths

A devoted family man, Murane’s focus has always been on providing for his wife and children. He seldom falls ill and only visits hospitals when accompanying his family.

Prostate screening is an unfamiliar concept to him, and the little he has heard about it only deepens his discomfort.

Tingidi Murane speaking about prostate cancer. (Charity Kilei)

Tingidi Murane speaking about prostate cancer. (Charity Kilei)

In his community, men rarely discuss health issues, particularly those related to reproductive organs. The topic is often met with ridicule, reinforcing a culture of silence.

"When a man has an issue affecting his reproductive health, he’d rather keep quiet and seek treatment silently. If such a thing is mentioned, people assume it’s an STD, and that becomes a laughing matter," he says.

Murane also believes prostate cancer is a disease of the elderly, primarily affecting men over 70. "People don’t live that long anymore," he reasons, dismissing any urgency to get screened.

His demanding job leaves little time for self-education, and the lack of awareness further solidifies his reluctance.

His perspective mirrors common barriers to prostate cancer screening—misconceptions about age-related risks, stigma, and limited access to health information.

Daniel Ngumbi, a boda boda rider, laments of the lack of information about prostate cancer. (Charity Kilei)

Daniel Ngumbi, a boda boda rider, laments of the lack of information about prostate cancer. (Charity Kilei)

For Daniel Ngumbi, reproductive health is an uncomfortable subject—one he would rather avoid. He only visits the hospital when his condition is severe, often at the insistence of his wife. His greatest fear is not just the examination itself but the possibility of discovering an illness he feels unprepared to handle.

"Imagine going for screening, and then they find something—what next? How does someone even process that? Sometimes, I’d rather not know than be diagnosed with more than one disease," he confesses.

"When it comes, we’ll deal with it." Until then, he prefers not to dwell on health concerns, particularly those related to reproductive health. He also laments the lack of awareness, pointing out that men rarely discuss such topics.

"When we meet as men, we talk about business, making money, and other things we consider important. I’ve only heard reproductive health mentioned once or twice in a chief’s baraza, but I didn’t pay much attention," he admits.

He believes that if health information were brought closer to men through grassroots initiatives led by local authorities such as chiefs or community barazas, it could make a difference. He suggests that if screening were organised in a way that respects men’s schedules, perhaps in designated spaces at convenient times, he might consider it.

Collins Ochieng, in his mid-40s, has heard about prostate cancer but knows little about screening—its importance, how it’s done, or where such services are available. Like many men, he values his privacy, especially when it comes to matters of reproductive health.

“I find discussing such topics very sensitive. Whenever I’ve had issues with my reproductive health, I’ve always turned to traditional medicine, and so far, it has worked for me,” he says.

His biggest concern about screening is the examination process itself. He worries about how it is conducted, fears it may be embarrassing, and is unsure how he will maintain his dignity. The idea of being examined by younger healthcare providers, especially women, makes him uneasy.

“Imagine going for an examination only to find the person handling it is young enough to be your daughter or son. Just the thought of it is distressing,” he admits.

Despite his reservations, Collins is open to the idea of screening, provided the process respects his dignity and does not subject him to unnecessary discomfort.

Prostate cancer is a disease in which abnormal cells grow in the prostate, a small gland in men that helps produce semen. It is one of the most common cancers in men, especially as they get older.

What experts say

Dr Catherine Nyogesa, a cancer specialist at Texas Cancer Centre Nairobi, notes that many men view screening as a threat to their masculinity or associate it with vulnerability, leading to reluctance. Deep-seated cultural beliefs and misconceptions further discourage proactive health measures.

Beyond personal fears, men also face practical obstacles such as the high cost of screening, transportation challenges, lack of follow-up care, and the need to take time off work. Additionally, systemic healthcare issues, including inadequate facilities, long wait times, and a shortage of specialists, contribute to delays in diagnosis and treatment.

“In many areas, healthcare services are limited, leading to long waiting times. Misunderstandings about positive test results, stigma, and mistrust in the system only add to the fear and hesitation,” Dr Nyogesa explains.

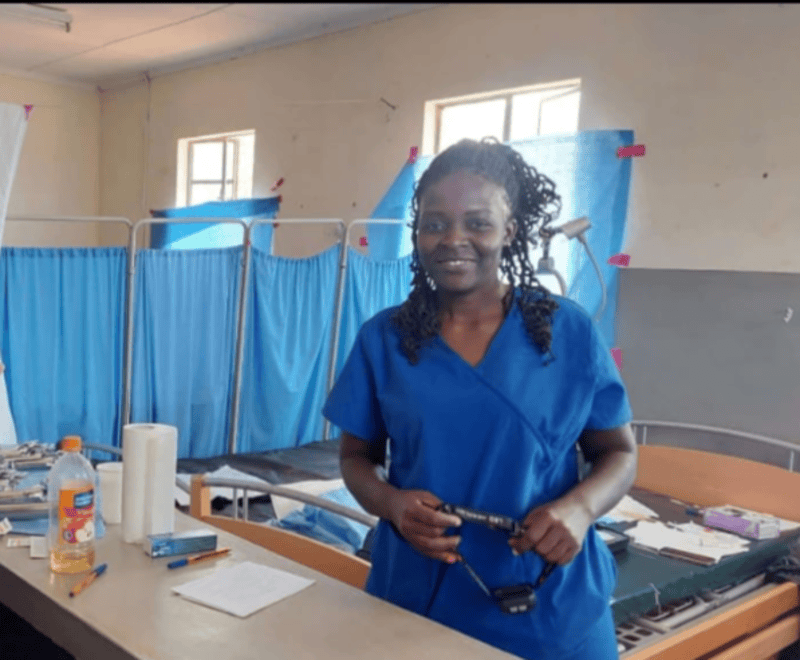

Dr Catherine Nyongesa, an oncologist from Texas Cancer Center. (Charity Kilei)

Dr Catherine Nyongesa, an oncologist from Texas Cancer Center. (Charity Kilei)

She emphasises the need for confidential screening services and widespread public awareness to address these barriers. She advises that men over 50, or those over 45 with a family history of prostate cancer, should prioritise screening. Symptoms such as difficulty urinating, blood in the urine, or unexplained pain in the lower back, hips, or pelvis should not be ignored.

In underserved regions, access to PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) testing is limited, meaning many men miss out on early screening opportunities. Younger men may feel invincible and overlook the need for testing, while older men, particularly in rural areas, may avoid it out of fear of diagnosis.

New medical technologies, including advanced biomarkers, MRI imaging, and telemedicine, are improving early detection. However, a critical shortage of oncologists and urologists—especially in rural areas—often leads to delayed diagnoses and inadequate specialist care.

"Many men avoid screening because they fear it means a death sentence. The stigma surrounding prostate cancer prevents them from getting tested, as they don’t want to face the judgement that comes with a diagnosis. Raising awareness, sharing success stories from survivors, and emphasising the importance of early detection can help change this mindset," she adds.

Dr Nyogesa advocates for private and dignified screening processes to encourage more men to participate. She also highlights the lack of insurance coverage as a significant barrier, calling for subsidised screening programmes and community engagement efforts to build trust and increase screening uptake.

Dr Maryanne Omenda, a specialist with Heart Africa, an organisation dedicated to supporting vulnerable communities, emphasises that while prostate cancer predominantly affects men over the age of 50, younger individuals are also at risk.

“The reluctance towards screening, particularly the Digital Rectal Exam (DRE), is often linked to feelings of embarrassment, which deter many men from seeking early detection. Additionally, the common misconception that prostate cancer is a condition exclusive to older men results in delayed screening. Unfortunately, by the time many patients receive a diagnosis, the disease has already progressed to advanced stages,” she explains.

Dr Omenda highlights that in many cases, men only seek medical attention at the urging of their spouses. Unlike cervical cancer, which is frequently addressed in public health initiatives, prostate cancer awareness campaigns remain limited, further contributing to low screening rates.

Dr Maryanne Omenda who works with vulnerable communities speak about prostate cancer. (Charity Kilei)

Dr Maryanne Omenda who works with vulnerable communities speak about prostate cancer. (Charity Kilei)

To enhance early detection, she advocates for the involvement of community leaders in baraza (public forums) to facilitate discussions and promote awareness.

“Access to prostate cancer screening remains limited in low- and middle-income regions, leading to disparities in early diagnosis. Additionally, inconsistencies in screening guidelines—some recommending screening from age 50 while others focus on high-risk populations—create confusion and hinder preventive measures,” she notes.

Another significant challenge is the perception that screening is unnecessary in the absence of symptoms.

“When prostate cancer is detected in its early stages, it is highly treatable through surgery or biopsy. However, late-stage diagnoses require more complex and resource-intensive interventions. Additionally, many men hesitate to discuss their health due to stigma and cultural norms,” she adds.

Dr Omenda stresses the importance of addressing cultural barriers, as men often prioritise their families’ needs over their own health. Encouraging open communication with healthcare providers is critical to overcoming these obstacles.

Prostate cancer ranks as the fourth most prevalent cancer globally, with mortality rates significantly higher in less developed countries. In Kenya, it is the most common cancer among men, accounting for 3,582 new cases (21.9%) according to GLOBOCAN 2022. It also stands as the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men, with a mortality rate of 24.4 per 100,000.

Top Stories Today