Fed but not nourished: The silent crisis facing children in Kenya’s informal settlements

According to Amos Kamau, Nutrition Advocacy Strategist at the Institute for Food Justice and Development and youth representative at the World Food Forum, the biggest challenge is that many parents do not recognise the early warning signs.

As children reach weaning age, many mothers begin introducing foods passed down through generations, soft porridge, ugali with soup, mashed potatoes, or plain rice.

These meals are familiar, affordable, and often considered sufficient. Yet beneath the surface lies a troubling reality: while they may fill a child’s stomach, they often fail to nourish.

More To Read

- UNICEF: Childhood obesity in Africa rising, surpassing underweight cases globally

- Africa’s agri-food trade more than doubles, but hunger still soars - report

- Turkana partners with Save the Children, UNICEF to strengthen fight against malnutrition

- Kenya hit hard as therapeutic food supplies dwindle

- Sudan: ‘Devastating tragedy’ for children in El Fasher after 500 days of siege

- African health ministers adopt regional framework to fight oral diseases

Sharon Cheptoo, a mother of two from Muthurwa, is among many caught in this cycle. She believed she was doing everything right.

"I feed my baby what I saw my mother feeding us growing up — porridge, ugali with soup, rice, sometimes mashed potatoes," she says. "Vegetables are rare because my baby doesn't like them."

Her one-year-old recently fell ill and lost significant weight. Despite breastfeeding and ensuring the child ate regularly, there was no improvement. Alarmed, she visited a clinic — only to be told her baby was underweight and showing signs of nutrient deficiency. At just six kilograms, the child’s weight was far below average for their age.

Confused

Sharon was confused. Her first child had never faced such problems. She assumed this one simply had a smaller body and a poor appetite. "I thought children are just different," she admits.

Her main concern now is understanding what a balanced diet truly means — and how to achieve it with limited income and little nutritional knowledge. Like many mothers, she often defaults to feeding her child familiar soft foods, without knowing if they meet nutritional needs.

Across poor urban communities, especially informal settlements, undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, and childhood obesity coexist, a phenomenon known as the triple burden of malnutrition. Though seemingly contradictory, all three can exist in a single household, and sometimes within the same child.

According to Amos Kamau, Nutrition Advocacy Strategist at the Institute for Food Justice and Development (IFJAD) and youth representative at the World Food Forum, the biggest challenge is that many parents do not recognise the early warning signs.

"Most people only react when they see extreme thinness," Kamau explains. "But there are many subtle signs that often go unnoticed — frequent illness, fatigue, pale gums, brittle hair or nails, and delayed growth. These are usually signs of micronutrient deficiencies, especially iron or vitamin A."

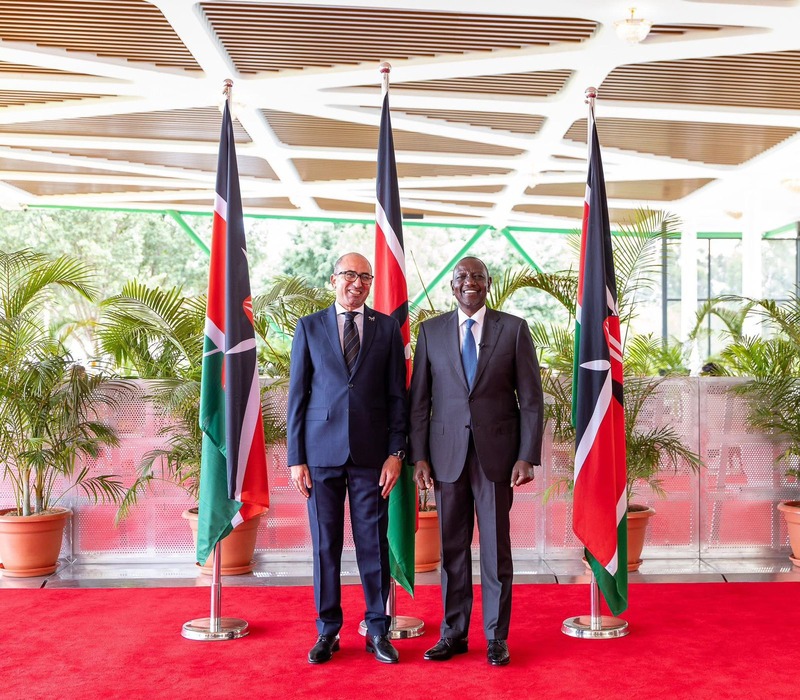

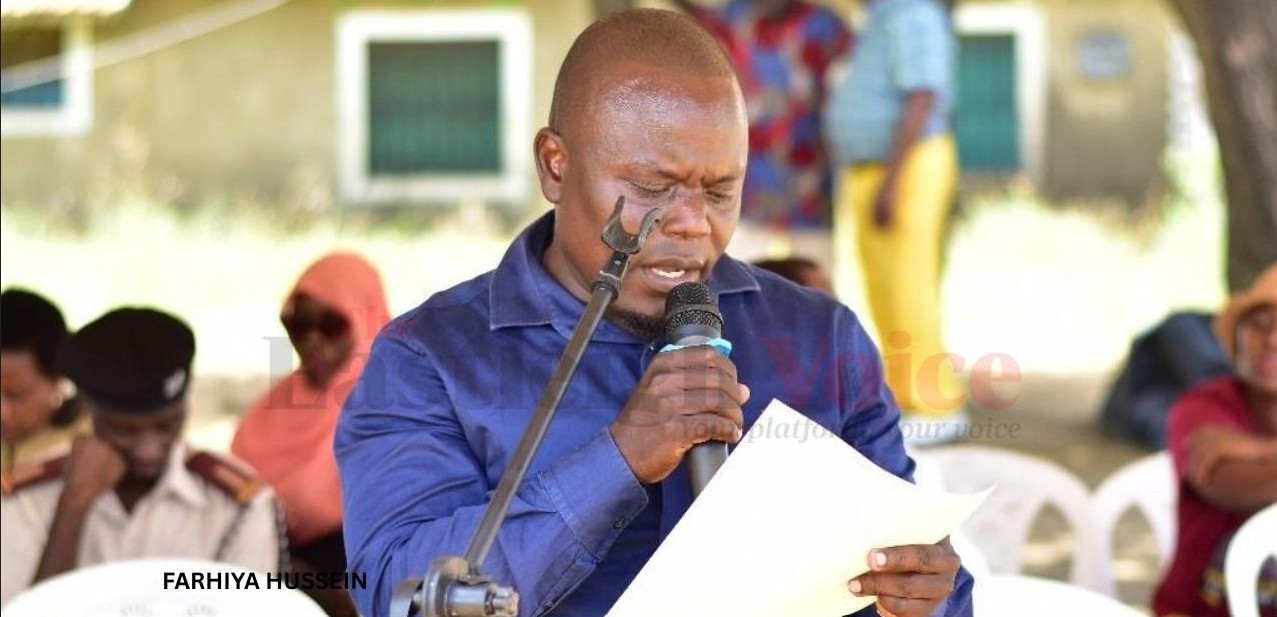

Amos Kamau, a nutrition advocacy strategist at the Institute for Food Justice and Development and a youth representative at the World Food Forum. (Photo: Handout)

Amos Kamau, a nutrition advocacy strategist at the Institute for Food Justice and Development and a youth representative at the World Food Forum. (Photo: Handout)

Multiple forms of malnutrition

He adds that many children in these communities suffer from multiple forms of malnutrition. Some are underweight from insufficient food or frequent infections, while their diets, heavy on cheap carbohydrates like maize, rice, or bread, lack vitamins and minerals.

Others, meanwhile, consume rising amounts of cheap processed foods, sugary snacks, fried street food, and fizzy drinks, putting them at risk of obesity and related health problems.

Kamau has also encountered widespread misconceptions. Some parents equate a full stomach with proper nutrition.

Others assume packaged foods are healthier because they appear modern, while many view vegetables, fruits, and milk as luxuries.

Food before six months

Perhaps most dangerously, many still introduce food before six months, convinced breast milk alone is inadequate — a practice that exposes babies to infection and malnutrition.

"The first six months of life should be exclusively breastfed," Kamau stresses. "Breast milk is perfectly tailored for an infant's needs. Anything else — porridge, tea, juice — disrupts that balance and can do more harm than good."

But malnutrition is not just about individual choices. In informal settlements, the food environment is defined by affordability and access. Most households rely on kiosks and roadside vendors selling quick, unhealthy meals.

Fresh produce is often costly or unavailable. Families living on unstable daily incomes prioritise filling meals over balanced diets. Above all, the lack of nutrition education leaves many parents guessing or relying on outdated traditions.

Community-driven solutions

Despite these challenges, Kamau sees hope in community-driven solutions.

Initiatives such as urban kitchens and container gardens are enabling families to grow vegetables. School feeding programmes ensure children receive at least one nutritious meal daily. And targeted nutrition education, especially through visuals and local languages, is slowly breaking harmful myths.

"Malnutrition isn't just about food. It's about knowledge, access, culture, and power," he says. "If we want to see real change, we must invest in education, affordable, healthy food, and strong public health policies that protect our most vulnerable — starting with children."

Until then, mothers like Sharon will keep doing their best with what they know — and many children will continue to be fed, but not truly nourished.

A 2019 study published in the Italian Journal of Paediatrics titled “Malnutrition, morbidity and infection in the informal settlements of Nairobi, Kenya: an epidemiological study” examined malnutrition among infants in Korogocho and Viwandani, two of Nairobi’s largest informal settlements.

These overcrowded, low-income neighbourhoods face poor housing, sanitation challenges, food insecurity, and limited healthcare, all factors contributing to poor child health.

Study findings

Using data from the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS), researchers analysed 3,567 children aged 0–11 months, making it one of the most robust studies on early childhood malnutrition in Kenya. The findings were stark:

• 26.3per cent of infants were stunted (chronic malnutrition).

• 13.2per cent were underweight (both acute and chronic undernutrition).

• 6.3per cent were wasted (severe recent weight loss).

The study revealed that wasting was highest among infants under three months, while stunting increased with age, peaking at 9–11 months, showing malnutrition begins early and worsens during weaning.

It also found strong links between infection and malnutrition. Infants with diarrhoea or respiratory infections were more likely to be wasted, highlighting the vicious cycle between poor nutrition and illness. Stunting, meanwhile, was tied to structural issues such as unsafe water, poor sanitation, and incomplete immunisation.

Children in homes without clean water or with inadequate toilets were far more likely to be stunted.

Another study, "Evidence of a Double Burden of Malnutrition in Urban Poor Settings in Nairobi, Kenya", covering over 3,000 children under five and 5,000 adults, revealed that nearly half the children were stunted, while many mothers were overweight or obese.

Some households even had stunted children and overweight mothers living side by side, underscoring how undernutrition and overnutrition coexist in the same environment.

Nationally, the 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) reported that 10per cent of children under five are underweight, 18per cent are stunted, and 5per cent are wasted.

UNICEF–WHO–World Bank joint estimates further showed that in 2024, there were about 35.5 million underweight children under five worldwide.

Top Stories Today