From NHIF to SHA: Kenya's cancer patients pay the price for a broken health system

Promises of better healthcare have turned into a nightmare for thousands of cancer patients, as system failures and unclear policies leave many fighting disease and despair alone.

When Judy Wanyoike was first diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2012, she felt a wave of fear and uncertainty. Yet, knowing that the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) could support her gave her a measure of comfort.

She had seen others receive treatment through it, and friends encouraged her to join. The cover was clear, inclusive, and free of hidden costs—allowing her to focus on recovery instead of bills.

More To Read

- MPs demand SHA clears Sh10 billion in pending NHIF bills within three months

- SHA transition sparks tension as teachers cite lack of consultation, legal violations

- Review meeting highlights barriers to immunisation, maternal health in Turkana

- Court of Appeal postpones hearing on constitutionality of Health Acts

- 1,567 injured police officers compensated, says Mwangangi as Senate pushes for transparency

- SHA announces refund process for mistaken M-Pesa premium payments

Now, as she battles spine cancer, her story is heartbreakingly different.

For months, Judy’s body had been warning her that something was wrong. She felt weak, constantly tired, and sometimes bled heavily for no reason.

Each time she sought help at a Dandora hospital, doctors referred her to Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH). Each time, she told herself she would go “next week.” But “next week” never came—she still couldn’t afford the transport, still hoped the pain would fade.

As a mother of three, juggling small jobs to keep her children in school, life was already difficult. The thought of long queues at KNH and the cost of tests felt impossible. So she endured—until her body forced her to stop.

During a visit to Nakuru, a pastor held a free cervical cancer screening in memory of his late wife. Judy seized the chance. But as the nurse began the screening, she started bleeding profusely.

Panic filled the small room. Trembling, she was rushed out and told to seek immediate treatment in Nairobi. Yet again, she lacked the money to travel. She spent the night restless and afraid, clutching her stomach and praying for help.

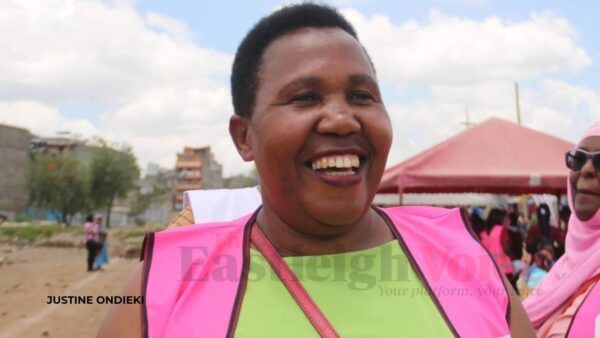

Cancer survivor Judy Wanyoike. Once supported by NHIF, she now struggles to afford spine cancer treatment under the new Social Health Authority. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Cancer survivor Judy Wanyoike. Once supported by NHIF, she now struggles to afford spine cancer treatment under the new Social Health Authority. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

“The next morning, I explained to the host, and they helped me. I was able to come to Kenyatta, and when I arrived, I was diagnosed with stage 2B cervical cancer. It had already eaten my womb, and in the process, I lost both my womb and my ovaries.”

The diagnosis shattered her. At just 35, she was still young—still dreaming of holding another baby. Losing that possibility felt like a wound that would never heal. Chemotherapy was brutal: her hair fell, her strength faded, and each hospital visit drained her emotionally and financially. But she persevered.

“It was a hard journey,” she said. “I would like to encourage other women to go for screening, because I didn’t, I lost my womb and ovaries. Now I am an advocate, urging women to get screened early.”

Cancer cost her more than medical bills. It stole her peace, her home, and her children’s futures. Her eldest son turned to drugs, her second dropped out of school, and only her youngest continued—barely. The stigma and financial strain nearly broke her.

“Cancer causes poverty,” she said softly. “Even my son didn’t get a good education. People talk — they say you are a burden. A woman must love herself; no one can love you unless you do.”

The NHIF once made her treatment possible. Paying Sh500 per month for a year wasn’t easy, but it saved her life. The cover supported chemotherapy and other treatments, with only small out-of-pocket costs. Everything was clear, structured, and dependable.

But now, under the Social Health Authority (SHA), things have changed. Diagnosed with spine cancer, Judy faces worse pain and higher costs. Despite paying her premiums faithfully, treatment is often delayed by slow approvals, exhausted benefits, and technical hitches. Some essential tests and drugs are not covered.

The pain of battling cancer while feeling abandoned by the system meant to protect her is, she says, “a pain of its own.”

Veronicah Mwangi’s story

When Veronicah Mwangi began her cervical cancer treatment in 2023, she never imagined it would test not just her body but her faith. She was among the last patients to start treatment under NHIF before the transition to SHA.

At first, she believed the new system would bring hope, efficiency, and better coverage. Instead, she found confusion, delays, and despair.

“The shock that awaited me was unbearable,” she recalls. “It caused great distress — more than I could have imagined.”

Battling cancer while trying to survive daily life became overwhelming. The high cost of living made every hospital visit harder.

“Imagine fighting for your life,” she says, “and at the same time begging people for help — only to be turned away because a test isn’t covered, or you’re told, ‘The system is down.’ Who wouldn’t be overwhelmed?”

The process grew increasingly unpredictable. Some chemotherapy sessions were covered, others not. Certain tests required cash payments, and drug prices rose without warning.

After months of treatment, she received devastating news: her annual coverage package was exhausted. She would have to wait until the next fiscal year to qualify again.

“It broke me,” she admits. “Because I knew missing treatment could mean the cancer would spread — it could mean death.”

Desperate, she turned to harambees—community fundraisers—relying on relatives, neighbours, and church members. Their support helped, but never enough. Some sessions were skipped; some drugs went unbought.

Even so, she refused to give up. She learned to live one day at a time, celebrating small victories.

“I just hope the government can truly help cancer patients,” she says. “It’s already a life-threatening disease — and these hurdles only make it worse. No one should have to beg for treatment while fighting for their life.”

Today, Mwangi fights on—not just against cancer, but for reform. She dreams of a day when health insurance means security, not uncertainty, and no patient must choose between food and chemotherapy.

The bigger picture

The situation under SHA has triggered widespread frustration and protests among cancer patients. Although SHA allocates Sh550,000 per patient annually—Sh100,000 for diagnostics and Sh450,000 for treatment—patients say this is far from enough to cover the steep costs of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and medication.

Drug shortages, especially of life-saving medicines such as Herceptin, have become common at major hospitals like Kenyatta National Hospital. Patients unable to afford private treatment endure dangerous delays and interruptions.

Long waiting times for PET-CT scans, radiotherapy, and pre-authorisation approvals add to their suffering. Even with SHA coverage, many patients still pay high out-of-pocket expenses or sell personal assets to continue treatment.

A lack of clear communication from SHA has left many confused about what the scheme actually covers. Advocacy groups, including the Kenyan Network of Cancer Organisations (KENCO), are demanding transparency on premiums, payment processes, and service entitlements.

KENCO warns that unless urgent reforms are made, universal and equitable health coverage will remain out of reach for thousands of Kenyan cancer patients, who will continue to face delays, unbearable costs, and preventable deaths.

Members of Parliament have pledged to push for an increase in the SHA cancer treatment package—from Sh400,000 to at least Sh1 million. Until then, patients like Judy and Veronica continue to suffer in silence.

Every year, about 27,092 Kenyans die from cancer, with cervical cancer causing 3,211 deaths—the highest among women. Lung cancer, ranked 11th, has a 92 per cent fatality rate.

In 2024, cancer became the second leading cause of death in Kenyan health facilities. Globally, the disease claimed 10.4 million lives in 2023, nearly one in six deaths.

Top Stories Today