Explainer: Wild vs vaccine-derived polio - why both threaten Kenya’s progress

While significant progress has been made in the fight against polio both in Kenya and globally, the country’s porous borders continue to pose a risk of re-infection.

As the world marked World Polio Day on October 24, the progress achieved offered hope; only 36 cases of wild poliovirus have been reported globally this year, a dramatic drop from 350,000 when eradication efforts began.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), this is one of the most successful public health achievements in history. Yet, Kenya continues to grapple with vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV), a rare but serious challenge in the global eradication effort.

More To Read

- Conflict, displacement fuelling measles outbreaks across the continent - Africa CDC

- WHO says polio eradication still feasible despite Sh219 billion funding cuts

- MoH says Kenya fully stocked on vaccines as Sh4.9 billion allocation secures future supply

- Kenya to receive BCG, polio vaccines next month - Health CS Duale

- Explainer: Why your child needs that polio vaccine

- Over 300,000 children vaccinated against polio in Garissa County

The oral polio vaccine (OPV), which contains a live, weakened form of the virus, has reduced global polio cases by over 99 per cent. It builds immunity by replicating in the intestines and can indirectly protect others through environmental spread.

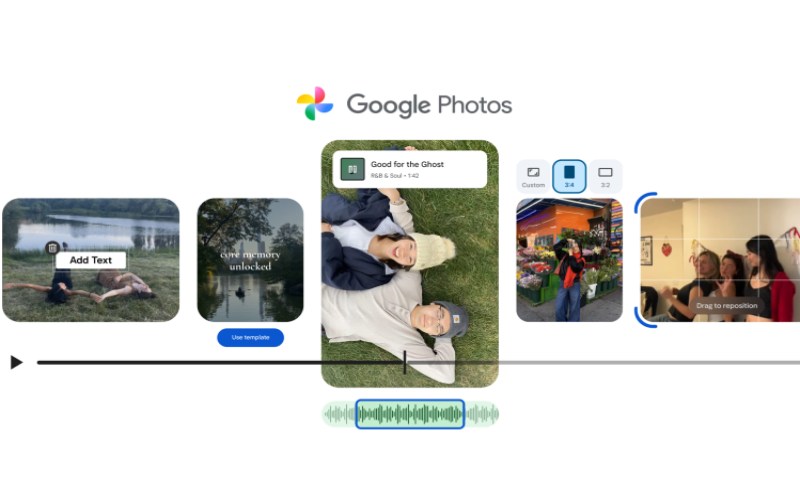

Polio vaccine

However, in areas with low vaccination coverage and poor sanitation, the weakened virus can circulate, mutate, and regain its ability to cause paralysis.

This mutated strain is known as circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV). Though rarer than wild polio, cVDPV can trigger outbreaks in previously polio-free areas, especially among unvaccinated populations.

In Kenya and across parts of Africa, outbreaks of cVDPV2, the most common vaccine-derived strain globally, have been reported. To address this, WHO and global partners introduced the novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2), a genetically stabilised version less likely to mutate.

Kenya began rolling out nOPV2 in 2021 as part of its strategy to prevent further outbreaks. Despite this, maintaining high vaccination coverage and sanitation remains critical to prevent both wild and vaccine-derived polioviruses from circulating.

In July 2023, four genetically linked cVDPV2 cases were detected in Kenya’s Hagadera refugee camp in Garissa County. Two children developed acute flaccid paralysis, while two others were asymptomatic contacts.

At the time, vaccination coverage in the camp stood at 77 per cent, compared to the national estimate of 91 per cent in 2021. By October 2024, Kenya had confirmed five cVDPV2 cases and one environmental detection, prompting a vaccination campaign targeting 3.8 million children under five in nine high-risk counties.

Earlier in August 2023, following infections among six children, two of whom were paralysed, the government launched an emergency drive to vaccinate 7.4 million children across ten counties in northern and eastern Kenya.

These campaigns have continued, with the February 2025 round reaching over 920,000 children in Mandera, Wajir, Garissa, and Marsabit. The repeated drives underscore the persistent threat of cVDPV2, especially in regions with low immunisation and poor sanitation.

Wild poliovirus

Unlike vaccine-derived types, the Wild poliovirus (WPV), a naturally occurring strain, spreads mainly through the faecal-oral route, especially in areas with poor sanitation.

It is highly infectious; a single infected person can spread the virus to dozens of others, particularly in unvaccinated communities.

Once inside the body, it multiplies in the intestines and can invade the nervous system, leading to irreversible paralysis, particularly in children under five. In severe cases, it can affect breathing muscles, leading to death.

Most infected individuals show no symptoms, but some experience fever, fatigue, muscle weakness, sore throat, or stiffness. In severe cases, sudden paralysis may occur, often affecting one side of the body. Paralysis is usually permanent and can be fatal.

According to the WHO, three types of wild polioviruses cause poliomyelitis: WPV1, WPV2, and WPV3. WPV1 is the only strain still in circulation, mainly in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

WPV2 was declared eradicated in 2015, and WPV3 in 2019. Kenya has been free of indigenous wild polio since 2020, but the threat of importation and cVDPV outbreaks remains.

Both wild poliovirus (WPV) and vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) are dangerous and can cause lifelong paralysis, but they differ in origin and transmission.

Vaccine-derived poliovirus

VDPV, on the other hand, develops from the weakened virus used in OPV.

While OPV has been instrumental in eliminating most polio cases globally, in areas with low vaccination rates, the weakened virus can circulate, mutate, and regain its ability to cause paralysis. This makes it particularly dangerous in under-immunised populations, where it can spread silently before detection.

Though both strains cause similar symptoms, outbreaks of vaccine-derived polio tend to occur in regions with dropped vaccination coverage, highlighting failures in herd immunity. Wild polio persists mainly in areas where it has never been eradicated.

Both forms can cause paralysis and even death if the respiratory muscles are affected. WPV is generally more aggressive and spreads more easily. VDPV, while rarer, represents a preventable setback in the eradication effort.

There is no cure for either strain; treatment focuses on supportive care. Prevention remains the best defence. High vaccination coverage using the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) and the newer nOPV2 can stop both wild and vaccine-derived strains from circulating.

Kenya's genomic sequencing

Kenya has, meanwhile, made significant progress in strengthening its polio surveillance and laboratory systems.

In 2025, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) upgraded its national polio lab to serve as an inter-country reference facility, enhancing rapid virus detection and genomic sequencing.

The country’s vaccination campaigns have reached millions, over 920,000 children in February 2025, 3.6 million in November 2024 (86 per cent of the target), and 6.5 million in a cross-border drive with Uganda.

Despite these achievements, reaching “zero-dose” children, those who have never received any vaccine, remains a major challenge.

An estimated 45,000 children in Kenya remain unvaccinated each year, particularly in refugee camps, border regions, and nomadic communities.

Combined with porous borders shared with Somalia, Ethiopia, and South Sudan, these gaps heighten the risk of virus reintroduction.

Top Stories Today