Understanding jaundice in newborns, its causes and treatment

Jaundice starts in the face and gradually spreads to the chest and legs as bilirubin levels rise.

After a gruelling period of labour and crying, Farida Mbaya was finally ready to head home with her newborn daughter, having packed her bags and wrapped her little one snugly in warm shawls. But just as she was about to leave, a routine check-up by the paediatrician threw her into anxiety.

As a first-time mother, she believed her baby girl was perfectly healthy. However, a thorough examination by the paediatrician revealed that her newborn had jaundice. This unexpected news left Farida deeply unsettled, suddenly cutting short her joy.

More To Read

- Tana River Senator seeks Senate health probe after pregnant woman dies from snakebite

- Africa’s hidden stillbirth crisis: New report exposes major policy and data gaps

- Governors sound alarm as 934 newborns die amid funding row in health sector

- Governors decry Health Ministry’s move to deny maternity funds to dispensaries

- Ministry of Health announces measures to reduce maternal, newborn deaths

- New study reveals why young mothers in Kenya are at higher risk of preterm births

“When the doctors mentioned jaundice, the first thing that flashed through my mind was a liver infection. A wave of fear washed over me. I felt a deep, unsettling anxiety about my baby’s health.”

Despite the tender moments she shared while breastfeeding, Farida had not noticed the yellowish tint in her baby's eyes. She was completely unaware of jaundice, a common condition that, if left untreated, could lead to serious complications.

With jaundice, a person’s skin and the whites of their eyes turn yellow. This happens because there’s too much bilirubin in the blood, which usually means the liver isn’t working properly.

It may occur if the liver efficiently processes red blood cells as they break down and is normal in healthy newborns and usually clears on its own.

“Initially, I was extremely frustrated when they refused to discharge us. I suspected it might be a scheme because I hadn’t noticed anything wrong. However, by the third day, I saw that my baby’s eyes had turned yellow, and I felt I must have missed it earlier. After counselling, I agreed to the treatment, which involved exposing my baby to blue light phototherapy,” said Farida.

For nearly three nights, she endured the heartache of being unable to hold her baby, who was left exposed to the harsh blue light of phototherapy.

“Watching my baby suffer in pain and cry under those intense lights, with her eyes covered, was deeply distressing,” Farida said.

Her baby’s skin began to peel, and she appeared completely pale. The experience was so overwhelming that Farida felt she was being cruel to her child. The worst part was the uncertainty about the cause of her baby’s condition, which left her feeling utterly confused and helpless.

Farida Mbaya breastfeeds her baby two days after giving birth to her. (Photo: Charity Kilei/EV)

Farida Mbaya breastfeeds her baby two days after giving birth to her. (Photo: Charity Kilei/EV)

After the treatment, they were finally permitted to go home and were advised to expose the baby to sunlight and attend regular check-ups.

For the next three years, everything seemed fine. However, when Farida gave birth to her second child, the baby was diagnosed with the same condition, but this time it was more severe.

"This time, I was determined to understand why my babies were being born with jaundice. However, my questions went unanswered as I once again struggled with the challenges of her condition," she said.

While the treatment for Farida's first child lasted about three days, the process for her second one was extended for over a week. This time, the baby was enveloped in blue lights that covered her entire body.

"The setup where my baby was placed under the lights was incredibly distressing. She was in this odd, basin-like unit that made it look like she was hanging, and it was heart-wrenching to see. It was enough to break any mother's heart. I cried myself to sleep, wondering why my babies had to go through such a painful experience," said Farida.

The peeling of her baby’s skin was severe, accompanied by noticeable paleness. Farida recalled receiving various forms of advice, such as applying breast milk to her baby’s eyes and exposing her to sunlight, hoping the condition would improve. Despite these suggestions, the thought of not treating her baby properly made Farida endure the process with great difficulty.

“After about seven days, we were finally discharged from the hospital. I was instructed to expose my baby to sunlight and return for regular bilirubin check-ups. However, my second baby later developed an umbilical hernia, and I wasn’t sure if it was due to all the crying or somehow related to the treatment process.”

Farida’s children are now growing up, with her eldest four years old and her youngest eight months old. But she remains deeply troubled by the lack of answers about what caused their jaundice. She was told it might be genetic, but this explanation did little to alleviate her uncertainty.

During her hospital stay, she saw that two other mothers were also kept in the hospital because their babies were born with jaundice. Witnessing their struggles only intensified Farida’s need for a clearer understanding of the condition.

Dr Varsha Hirani, a paediatrician at MP Shah Hospital in Nairobi, explained that neonatal jaundice is a common condition.

“Neonatal jaundice usually results from high red blood cell counts and an immature liver that has difficulty processing bilirubin through urine or stool. Contributing factors can include inadequate breastfeeding, breast milk proteins, blood incompatibility, prematurity, infections, or birth bruising.”

Jaundice typically starts in the face and gradually spreads to the chest and legs as bilirubin levels rise, which may lead to lethargy, poor feeding, and a high-pitched cry.

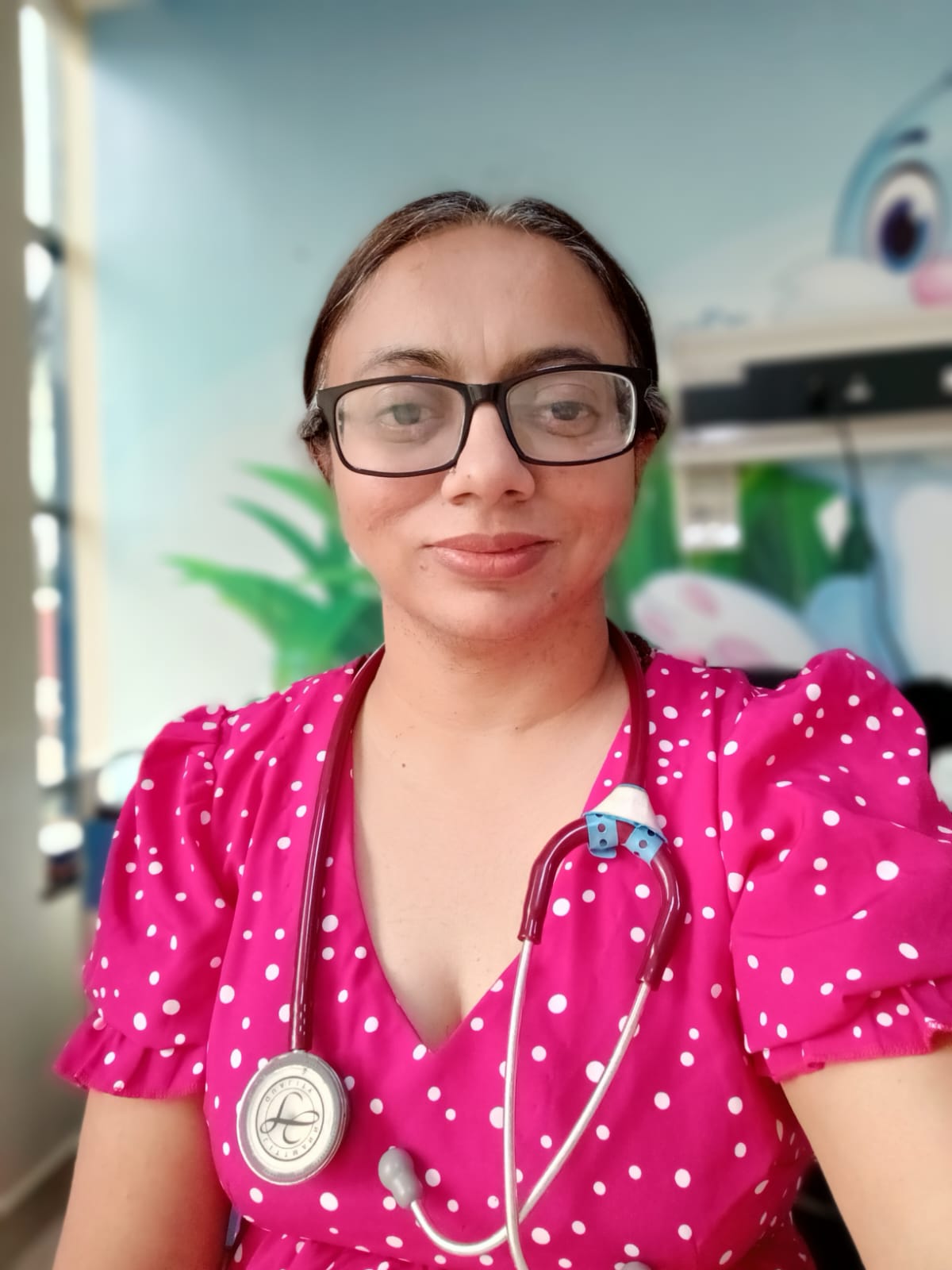

Dr Varsha Hirani, a paediatrician at MP Shah Hospital. (Photo: Handout)

Dr Varsha Hirani, a paediatrician at MP Shah Hospital. (Photo: Handout)

“When a baby has jaundice, their skin and eyes appear yellow due to elevated bilirubin levels, which occur when red blood cells break down and release bilirubin. Excess bilirubin leads to this yellowing of the skin and eyes,” Hirani said.

Common causes of jaundice include dehydration, infections, ABO (blood type) incompatibility, and genetic disorders. In some cases, jaundice may persist if there are underlying liver issues.

Hirani explained that if jaundice appears around three days of age, it is usually physiological jaundice, which often resolves on its own with continued breastfeeding. However, if jaundice is due to other causes, it may require more attention and intervention.

Pathological jaundice, which is caused by infections, metabolic issues, Rh factor problems, or ABO incompatibility, requires careful monitoring and treatment. Breast milk jaundice, another type, results from substances in the breast milk and typically resolves as the baby’s digestive system matures. Additionally, jaundice can be hereditary, stemming from metabolic disorders passed through genetics.

“Measuring bilirubin levels is essential to prevent severe complications, as untreated jaundice can lead to permanent brain damage,” said Hirani.

Treatment generally involves phototherapy, where the baby is placed under special lights. In some cases, additional interventions, such as adding haemoglobin or exchange transfusions may be required.

“While exposing the baby to sunlight can help reduce bilirubin levels if they are not excessively high, it should not replace proper medical treatment,” Hirani said, adding that mothers with newborns should be educated about it before discharge.

A major challenge is the lack of resources to assess metabolic levels in mothers, which could aid in preventing jaundice.

According to a study conducted by Laving, Hassan, and Aluvaala in 2020 and published in the East African Medical Journal, the prevalence and causes of prolonged neonatal jaundice were investigated at Kenyatta National Hospital.

The researchers analysed 360 patient files of neonates diagnosed with jaundice. They found that 56 of these neonates, or 16 per cent, had prolonged jaundice. This condition causes jaundice lasting beyond 14 days in full-term infants and 21 days in pre-term infants.

Among the neonates studied, there were 67 preterm and 293 term babies, with 91 per cent exhibiting conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. A full blood count was conducted in 93 per cent of the cases, but fewer than 50 per cent received additional first-tier diagnostic tests.

The study identified several causes of prolonged jaundice, with viral hepatitis (25 per cent) and bacterial sepsis (23 per cent) being the most common. Other causes included biliary atresia (4 per cent) and cholecystitis. During the initial hospital admission, the mortality rate was notable, with one out of eight preterm neonates and four out of 48 term neonates dying.

While international guidelines recommend comprehensive diagnostic workups for prolonged neonatal jaundice, such practices are often difficult to implement in developing countries like Kenya. Despite these challenges, infections were the most frequent cause of prolonged jaundice, and the short-term mortality rate among affected neonates was 10 per cent.

Top Stories Today