Healthcare data gap hindering proper policymaking in developing nations

One prominent example of the gap in localised healthcare data can be seen in the area of smoking cessation and harm reduction strategies.

In many low and middle-income countries like Kenya, the lack of robust and localised healthcare data remains a significant challenge. This data gap creates a barrier to effective policymaking, hinders the development of tailored interventions, and limits the ability to address public health issues in contextually relevant ways.

In countries like Kenya, the absence of locally generated research and evidence-based strategies often results in the reliance on data and health models from regions with different healthcare systems, cultural norms, and socioeconomic realities. These imported models may fail to capture the unique needs and circumstances of African populations, ultimately undermining the success of public health initiatives.

More To Read

- Ruto defends health reforms, cites 27 million Kenyans registered under new coverage

- Only six in 10 Kenyan health facilities adequately equipped for quality care - report

- Report lays bare Kenya’s failing healthcare system

- Data gaps threaten Kenya’s health goals as key indicators on mental health, drugs go unmeasured

- WHO sounds alarm: Antibiotic resistance rising fast, puts millions at risk worldwide

- WHO warns of alarming teen vaping surge as 15 million adolescents now using e-cigarettes

Localised data is crucial in understanding the specific health challenges faced by a population. For example, Kenya's healthcare system has long struggled with high rates of infectious diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/Aids, as well as emerging challenges like non-communicable diseases (NCDs) including hypertension, diabetes, and cancer.

While these health issues are common across the globe, the prevalence, risk factors, and social determinants of health vary greatly between regions.

In Kenya, factors such as poverty, limited access to healthcare, cultural practices, and infrastructure challenges all influence the health landscape in ways that may differ from countries in North America or Europe.

Without high-quality local data, policymakers and healthcare experts in Kenya often resort to using models based on research conducted in other parts of the world. This reliance on foreign data can lead to poorly informed decisions that may not work in the local context.

For instance, interventions that are effective in wealthier countries with better infrastructure, such as smoking cessation programmes or treatments for NCDs, may not be as successful in Kenya without considering the economic barriers, health literacy, and healthcare access issues that Kenyan citizens face.

Smoking cessation in Kenya

One prominent example of the gap in localised healthcare data can be seen in the area of smoking cessation and harm reduction strategies.

While harm reduction approaches like e-cigarettes and nicotine replacement therapies have gained traction in many high-income countries, there is a notable absence of studies or programmes assessing the effectiveness of these interventions in Kenya or other African countries. This lack of local research raises critical questions about whether these strategies would work in the Kenyan context.

Kenya has a significant smoking problem, with studies estimating that around 10 per cent of adults are smokers, and this number is steadily rising, especially among younger populations.

The country has made progress in some areas, such as the implementation of tobacco control policies under the World Health Organisation's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), but there is still a long way to go in reducing the overall smoking rate. While harm reduction strategies have shown some promise in helping people quit smoking in countries like the United Kingdom or the United States, their applicability in Kenya remains uncertain.

The health and economic impacts of smoking in Kenya, including rising rates of lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory illnesses, are undeniable. However, with little local data on the potential benefits of harm reduction, Kenya's policymakers and healthcare professionals are left in a state of uncertainty when considering such interventions.

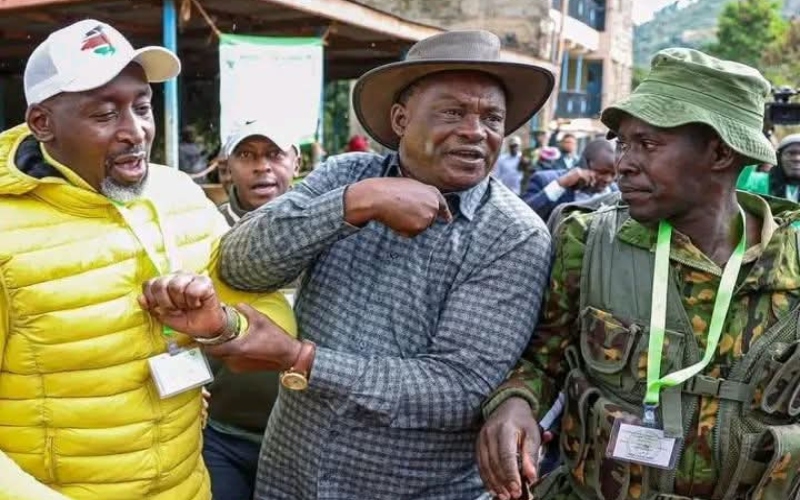

At the 4th Harm Reduction Exchange, various stakeholders voiced concerns about the lack of data.

Speaking at the forum, Issa Wone stressed the importance of incorporating qualitative data into decision-making processes, while acknowledging the scarcity of such data.

"Although we may not have quantitative data in Africa, we do have qualitative data that can guide decision-makers," he said.

Several leaders also highlighted the challenges, including insufficient government funding for research, which has contributed to the overall lack of data.

Furthermore, the economic disparities in Kenya also play a role in determining the feasibility of such harm-reduction strategies.

In wealthier nations, individuals may have greater access to healthcare services and disposable income to afford products like e-cigarettes or nicotine patches. However, in Kenya, these alternatives may not be as accessible or affordable to the majority of the population, particularly in rural areas or among lower-income groups.

This raises concerns about the equity of such interventions and whether they would only benefit the urban elite, further widening the healthcare gap.

Need for more localised research

The lack of localised research in Kenya extends beyond smoking cessation. A similar situation exists concerning other health interventions and policies. For example, Kenya has implemented vaccination campaigns to address diseases such as measles and polio, and more recently, the Covid-19 vaccine rollouts.

While these efforts have been largely successful, questions remain about the long-term effectiveness of vaccination strategies in the context of local health systems and community engagement.

How can Kenya ensure that rural populations, who are often disconnected from healthcare services, receive timely and accurate information about vaccination programs? Can mobile health technologies, such as SMS reminders, improve vaccination coverage in remote regions?

Another example lies in the growing burden of non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases. The rise of these diseases in Kenya is attributed to a combination of factors, including urbanisation, dietary changes, and a sedentary lifestyle.

However, Kenya's healthcare system remains ill-equipped to handle this shift, with insufficient data on the prevalence of NCDs, their risk factors, and the effectiveness of existing treatment protocols. Policymakers and healthcare providers often have to rely on general data from global health organisations, which may not fully capture the nuances of the Kenyan healthcare environment.

The lack of localised healthcare data in Kenya presents a significant challenge in the fight against the country's health issues. The example of smoking cessation and harm reduction highlights the broader issue of relying on data from outside the region, which may not apply to the Kenyan context.

Moving forward, the emphasis should be on strengthening local research capabilities and collecting data that reflects the realities of healthcare in Kenya. Only then can policymakers and healthcare experts develop and implement interventions that truly address the country's unique health challenges.

Top Stories Today