In a quiet community on Doha’s edge, Gaza’s wounded and orphaned learn to heal

Once built to host football fans during the 2022 World Cup, it now functions as an emergency housing and medical rehabilitation centre, with living quarters, a 24-hour primary health centre, physiotherapy and prosthetic rehabilitation units, counselling and social support spaces, and buildings repurposed for children’s activities.

In the late afternoon light, about 20 kilometres from Doha, the Al-Thumama complex looks like any quiet residential neighbourhood: paved pathways, rows of apartment blocks, the hum of air-conditioning carrying through the warm desert air.

When Annalena Baerbock, President of the UN General Assembly (PGA), visited the complex on Monday afternoon, the sun was beginning to soften over a place that has been transformed. UN News accompanied the visit, observing her meetings with families, children and the staff supporting them.

More To Read

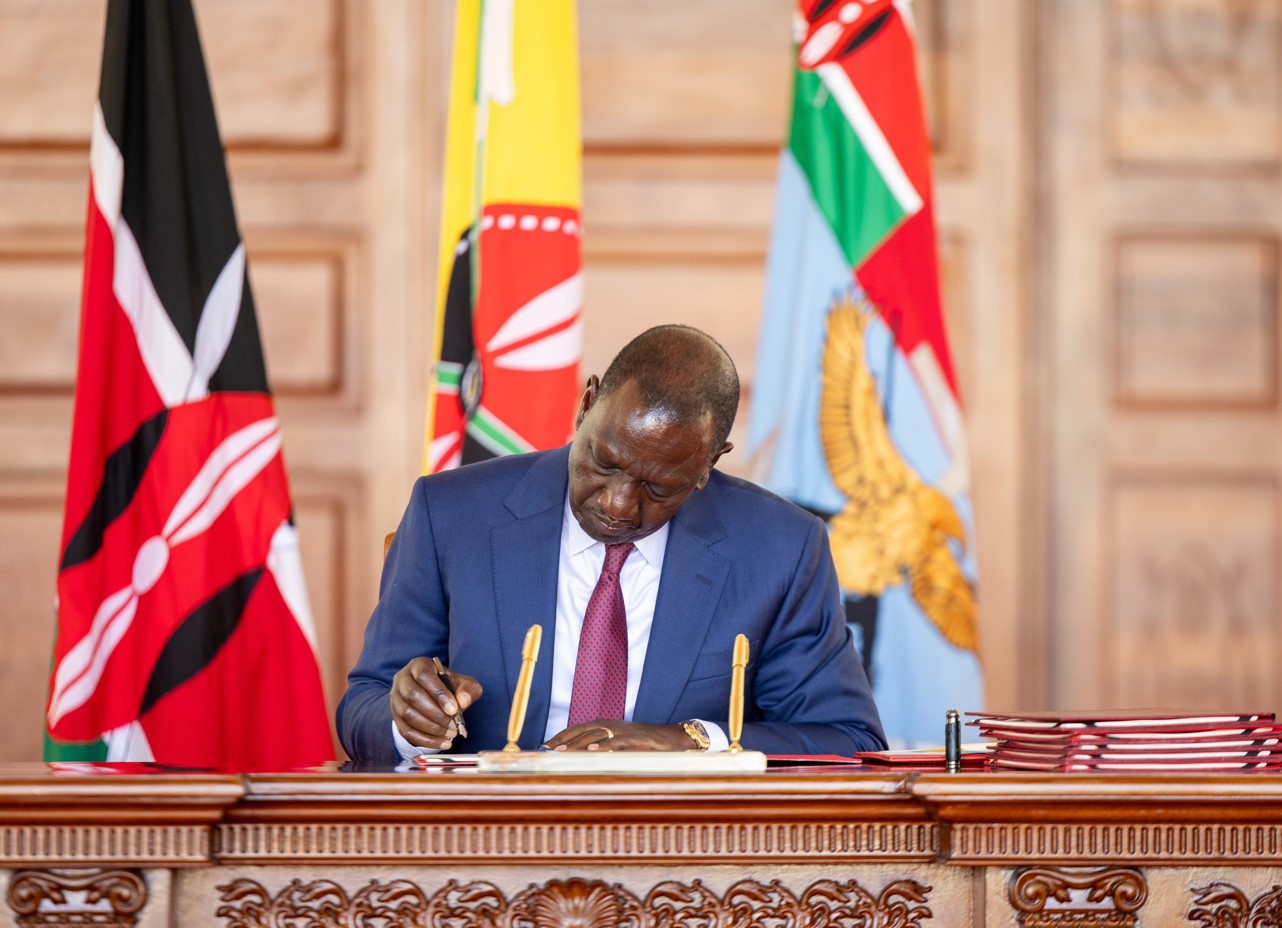

- Ruto amplifies Africa’s voice, calls for justice and inclusion at Doha summit

- President Ruto urges global unity to fight poverty, inequality at Doha summit

- ICJ tells Israel to let UN aid flow into Gaza – but UN’s own failures throughout the war loom large

- UN report accuses over 60 governments of enabling Gaza genocide through arms and trade ties

- Gaza: 91 Palestinians killed in Israeli airstrikes as truce falters

- Kenyan Muslims mark one year of humanitarian support for Gaza with major Nairobi event

Once built to host football fans during the 2022 World Cup, it now functions as an emergency housing and medical rehabilitation centre, with living quarters, a 24-hour primary health centre, physiotherapy and prosthetic rehabilitation units, counselling and social support spaces, and buildings repurposed for children’s activities.

Assembly President Baerbock (centre) speaks to a young girl at the complex. (UN News/Abdelmonem Makki)

Assembly President Baerbock (centre) speaks to a young girl at the complex. (UN News/Abdelmonem Makki)

Al-Thumama shelters between 1,700 and 2,000 evacuees from Gaza, including more than 700 children – many of them orphans now in the care of relatives or guardians who accompanied them from the Strip. The complex was originally built to accommodate 1,500 people.

Many residents are also undergoing medical treatment, ranging from surgery to long-term rehabilitation and prosthetics.

“Everyone who arrived here was diagnosed with PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder],” Sheikha Al Jufairi, a member of the Qatar Social Work Foundation, told the PGA.

Simply being children

As the briefing concluded, several women and children entered the room to greet the delegation. One girl wore a sweatshirt printed with the word “Brooklyn”. Annalena smiled and told her, “I’m from New York – where Brooklyn is,” prompting shy laughter.

Nearby, a small girl in a white floral dress, hair tied neatly with a ribbon and golden shoes that caught the light, leaned gently into Annalena’s side as they posed for a photo together. She moved with a slight limp, but her expression was all joy – present in the moment, simply being a child.

Assembly President Baerbock (left) speaks with a young boy, Ramadan. (UN News/Abdelmonem Makki)

Assembly President Baerbock (left) speaks with a young boy, Ramadan. (UN News/Abdelmonem Makki)

A grandmother sat nearby, carrying a boy not yet three years old, tall for his age. His right arm was amputated, and on his left remained only a single index finger, his small hands marked by the deep scars of war and medical treatment.

Then, a boy of about twelve or thirteen stepped forward – neatly dressed in a turquoise button-down shirt and dark trousers, composed and confident beyond his years.

He explained that he had written a book – A Biography of Childhood and Heroism: Memoirs of a Child from Gaza. He presented a copy to Annalena, who asked him to write his name inside. She told him: “I am taking your name, Ramadan, so I can tell the story about the strong children from Gaza, the brightest children I’ve met.”

After the visit, Annalena – who is in Doha to attend the UN World Summit for Social Development – said the encounter underscored the stakes for the future.

“Speaking to children, speaking to families at the Al-Thumama complex underlined how important it is not only to reconstruct Gaza, but to give support to a traumatised generation – children who have lost everything, their mothers, their fathers, relatives and friends, their arms, their legs, but still keep on fighting and wishing for a final future in peace.”

A heart and a sunflower

After the meeting, Annalena stepped out and crossed the street to an off-white building opposite. Inside, staff from the Qatar Red Crescent run mental health and psychosocial support services.

Inside the first room, a woman was working with a long strand of wool, guiding it through a handheld device to embroider a heart shape onto a carpet mat.

Coincidentally, the yarn matched the deep tone of the dress Annalena was wearing. Nearby were two completed pieces: one a pink-and-white sunflower, the other a cheerful multicoloured one, the sort a child might draw.

A woman embroiders a pattern on a fabric, tracing the image from a mobile phone. (UN News/Vibhu Mishra)

A woman embroiders a pattern on a fabric, tracing the image from a mobile phone. (UN News/Vibhu Mishra)

In the next room, several older women sat together around a table, embroidering by hand. One had a mobile phone in front of her with a pattern. The woman’s hand deftly needled the thread through the fabric, tracing an emerald and violet flower. No one spoke loudly; the atmosphere was one of gentle concentration.

A display case on the wall had small items the women had made: keychains, soft toys, and cloth purses – each arranged with care. Annalena paused to speak with the women, who continued working as they chatted.

As she left the building, a small detail stood out: every entrance had both steps and a ramp – a reminder that many residents here are still learning to walk again, or move with assistance.

Outside, an older woman in a wheelchair waited. From a bag, she offered small plates of homemade sweets to the PGA, who accepted one and thanked her. The exchange was brief, direct and warm.

Please ring the bell

A short walk away, another building housed a 24-hour primary health centre. Posters on the walls – on flu symptoms, vaccination reminders, and handwashing – could have been found in any clinic anywhere in the world.

Assembly President Baerbock (left) speaks with doctors at the complex's health clinic. (UN News/Vibhu Mishra)

Assembly President Baerbock (left) speaks with doctors at the complex's health clinic. (UN News/Vibhu Mishra)

Doctors in scrubs greeted the delegation, explaining the kinds of treatments provided, and how it coordinates with other, more advanced medical centres in Doha.

In one room, a nurse sat at a standard check-up desk; in another, a treatment room held a rolling hospital bed, a blood pressure monitor, a thermometer, and an oxygen cylinder standing ready at the wall.

Next door, the laboratory provided diagnostic services, and around the corner, a small pharmacy displayed a sign that read: “In case of emergency, please ring the bell.”

The ordinariness of the setting – the routine, the small objects, the soft-spoken interactions – stood in contrast to the extraordinary circumstances that brought everyone here.

Top Stories Today