The war on words: Smear campaigns and disinformation targeting Africa Uncensored

Kenya has a strong tradition of investigative journalism. Freedom of expression is enshrined in Article 33 and freedom of the media in Article 34 of the Constitution of Kenya (2010). However, the Media Council of Kenya has recorded at least 612 cases of violations of press freedom in the country from January 2013 to September 2024, including violations of journalists’ protection and safety.

The main perpetrator of violence against journalists and other media practitioners is the Kenya Police, with the majority of attacks against journalists in the line of duty not being reported due to a fear of victimisation on the part of journalists, and in instances when they are reported on, they often go unpunished, indicating the likelihood of an entrenched culture of impunity on the part of the authorities.

More To Read

Kenya has a robust and visible online community, and as a result, many Kenyans access information through the internet, with others going online first to get information before using other sources to verify the news they have seen. This transformation of the online space into a ‘clearing house’ of information means that social media is seen as a viable space to influence people’s perceptions, leading to the emergence of accounts paid to post content, many of which are used to advertise and amplify certain hashtags and promote brands online. However, some accounts have been used to push negative campaigns, with some online actors being paid to directly harass and discredit journalists, judges, and civil activists on Twitter (now X).

One result of this growing online community is the increasingly prevalent phenomenon of attacks against journalists being carried out online, with coordinated inauthentic behaviour, defined by Meta as coordinated efforts to manipulate public debate for a strategic goal, in which fake accounts are central to the operation. These online attacks are often carried out with the intent to distort public opinion around certain issues, and the result is often a distortion of the discourse around these issues, made worse by the anonymous nature of online exchanges, features such as Trending Topics on X being hijacked to push certain messages, and the ease through which bots and sockpuppet accounts can be set up.

The goal of these highly coordinated campaigns appears to be the degradation of online discourse around key subjects, and identifying the main actors in the creation and propagation of key stories that highlight and amplify critical issues in Kenya, as seen in the reaction to some of the stories that Africa Uncensored has produced. Interestingly, one outcome of these stories is the weaponization of networks to amplify pro-government narratives in order to distort and redirect conversations online away from the key issues identified and focus them on the individuals, such as John-Allan Namu, in the case of Africa Uncensored.

The aim of this study is to identify the main actors behind these campaigns and the tactics that they use to hijack conversations online to advance certain narratives. This study will also highlight the sources and patterns of disinformation, the actors, and the most common narratives that they use to hijack and derail the otherwise free flow of credible information online.

This investigation looks into attacks toward Africa Uncensored based on its coverage of the March 2023 protests, its May 2024 story on fake fertilizers, and also its coverage of the June 2024 Anti-Finance Bill protests. The report also looks into coordinated inauthentic behaviour, targeting the work of Africa Uncensored as well as other relevant media actors, in order to identify trends and patterns in online disinformation campaigns, outlining the findings, and making recommendations for key actors to implement.

Attacks against journalists

Kenya is currently ranked 102nd out of 180 in the press freedom index by Reporters Without Borders with events negatively impacting this rating. This includes the brutal murder of Pakistani journalist Arshad Shariff by police in October 2022, a murder that was dismissed as a fatal case of mistaken identity. Since then, Kenya has witnessed unrelated periods of civil unrest due to various factors, chiefly a worsening economy and cost of living.

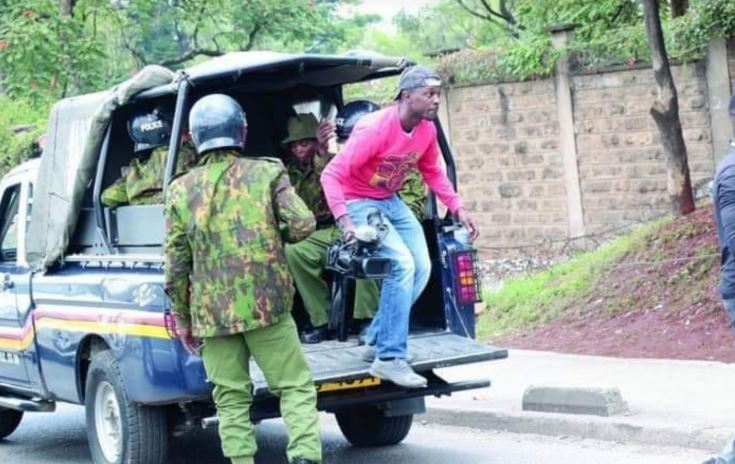

Africa Uncensored journalists were among those covering anti-government protests in Nairobi in 2023. On July 20, 2023, Azimio TV, an account on X connected to the opposition Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), published a photo online showing a man carrying a camera and claimed that this showed police officers masquerading as journalists. The photo was circulated extensively online, with some claiming that this was evidence that the police were acting in a way that violated the rules of standard practice.

Facebook post falsely identifying Africa Uncensored cameraman Clint Obere as a police officer.

Facebook post falsely identifying Africa Uncensored cameraman Clint Obere as a police officer.

However, the photo showed Africa Uncensored cameraman Clint Obere, who was released after his arrest while covering protests in Mathare months earlier, in March 2023. Clint was arrested along with Calvin Rock, another reporter and fact-checker also attached to Africa Uncensored, but both were released shortly after. Despite their release, posts resharing the claim had reached at least 100,000 users on X and Facebook through posts shared by politicians and affiliates of political parties involved in the protests.

A day before these false claims surfaced, on July 19, 2023, Calvin Rock had been briefly arrested while photographing illegal arrests by police using unmarked vehicles. Rock was taken to Kayole Police Station where his press identification was confiscated along with his camera and he was forced to delete all the photographs taken at the scene. This was deliberate to conceal identification for any potential investigations into illegal vehicles used by police during protests, a tactic highlighted by Africa Uncensored at the time.

Lastly, Thomas Mukhwana, also a reporter at Africa Uncensored was taken into police custody, this time during the June 2024 anti-Finance Bill protests. This was despite him wearing his press identification. Thomas was released shortly after being taken into custody following the intervention of his colleague, Elijah Kanyi, who informed the officers that Thomas was a journalist and that he had a press card and identification from the Media Council of Kenya to this effect. He was also shot in the foot at close range with a teargas canister on a separate day by police while recording the assault and violent arrest of unarmed peaceful protesters, which was documented in a video recorded during the harassment.

On the same day that Thomas was arrested, NTV journalist Maureen Mureithi was hit by a water cannon deployed by police to control and disperse crowds, and another NTV journalist, Ibrahim Karanja, was captured on video condemning police for their actions targeting protestors. Africa Uncensored cameraman Elijah Kanyi also recorded an incident of police firing teargas directly towards a group of journalists who were gathered at the Supreme Court, disregarding the fact that they were wearing identification that showed they were members of the press.

Similarly, Catherine Wanjeri, a journalist with Mediamax was deliberately shot in the leg by police officers while covering protests in Nakuru. These incidents during the protests highlight a trend of attacks on journalists by police officers who were either directly targeting journalists in some instances, while in others they were indiscriminately carrying out orders to thwart protestors without ensuring that anyone identified as a member of the press would not be targeted – an indication that they were not following standard operating procedure.

Legal tactics: Strategic litigation against public participation lawsuits (SLAPP)

Because of its role in highlighting issues of significant public importance, Kenyan media houses have been targeted with litigation and court cases, often when their coverage touches on public figures and highlights important issues. The use of strategic litigation against public participation (SLAPP) lawsuits to ensure that anyone who would report on these issues is increasingly becoming the go-to strategy to muzzle the press, as these cases carry hefty legal fees, require repeated court appearances and may rely on subjective readings of the laws involved. This is happening at a time when journalism is struggling to stay afloat due to shrinking revenues and growing costs, and the threat of a suit may often be enough to get a story killed.

Before the publication of Fertile Deception, Africa Uncensored received a court injunction from Joe Kariuki, the main character featured in the documentary, following the publication of a trailer showing what the production contained. This injunction aimed to halt the publication of the documentary, and was scheduled for Friday the 8th of March, timed to prevent an appeal as the courts do not sit on weekends.

As a result of this challenge, Africa Uncensored had to take on legal counsel to respond first to the accusation that the documentary was effectively an attack on Joe Kariuki’s character, and secondly, that it would not be in the public interest to release this documentary. In the end, the case was thrown out for lack of merit. But that wasn’t the first time Africa Uncensored faced a Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation case (SLAPP) post-publication.

A case was filed at a Kenyan court in 2023 following the publishing of an episode of Title Deals, a series produced by Africa Uncensored producer and investigative journalist Joy Kirigia. The series exposed historical land corruption in Kenya aided by officials in the Ministry of Land and government officials dating back to post-independence Kenya. One of the characters involved in land fraud, Eric Lugalia, sued for defamation and as a result, the premiere episode was taken down pending a court hearing and decision.

The ‘Ford Foundation’ attack

Amid pro-good governance protests on July 15, 2024, in a speech, President William Ruto accused the Ford Foundation of sponsoring violence. “Shame on them because they are sponsoring violence against our democratic nation,” Ruto said to a cheering crowd.

AI-generated image shared on Facebook blaming Ford Foundation for ‘ruining our country’

AI-generated image shared on Facebook blaming Ford Foundation for ‘ruining our country’

“We ask the Ford Foundation to explain to Kenyans its role in the recent protests. We will call out all those who are bent on rolling back our hard-won democracy,” Ruto doubled down in an X post shortly after. The post shared on X was followed by a letter from the Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs addressing Ford Foundation’s President Darren Walker.

Attacks against other media actors

The Nation Media Group, the largest independent media house in East and Central Africa was also the subject of various attacks, which Africa Uncensored documented extensively.

One attack claimed that the media house was using ink that contained carcinogenic substances. This attack used fabricated notices from the Kenya Bureau of Standards claiming that the Nation Media Group and the Standard Group used carbon black ink in their products. Carbon black is the main pigment in black printing ink, but there are calls for it to be banned because it is considered potentially carcinogenic.

This attack came after the Nation Media Group launched an investigative series, Broken System, shedding light on the challenges Kenyans experience in accessing government services. The series, which started on January 30, 2024, exposed several failings in the system that kept Kenyans from accessing public services, including neglected patients at the Kenyatta National Hospital – Kenya’s largest teaching and referral hospital, officials soliciting bribes for passport issuance, and pensioners begging for their dues to no avail.

The Kenya Bureau of Standards later dismissed the notice as fake, but however, a coordinated campaign had already gained traction online attacking NMG and Standard Group with the hashtags #WhatIsNationHiding, #KEBSPublicAlert and #NMGCancerInk.

Many of the accounts used to promote this campaign were also linked to another campaign targeting Nation Media Group dubbed #DearAgaKhan, as well as another coordinated misinformation campaign alleging that Maryanne Keitany was behind the fake fertilizer scandal exposed by Africa Uncensored.

130 accounts used the #DearAgaKhan hashtag, with over 5,000 mentions in posts and reposts shared within a one hour period on February 1, 2024. One of these accounts, @africmumke_ with over 8,970 followers, was involved in at least five other promotional and political hashtags between April 4 and April 14, 2024 – #KALROSPLaunch24, #ScrambleforGEMA, #UhuruShutUp, #NotAnotherKenyatta, and #FixingUhurusMess.

The strong correlation among these accounts involved in attacking Africa Uncensored, Nation Media Group, and to some extent the Standard Media Group, implies that the goal is to intensify the public’s distrust of media in Kenya, portraying them as being biased and unreliable whenever they publish information in the public interest, and further, potentially making them unattractive to advertisers.

The impact

The main goal of these actors appears to be the erasure of trust in the media as an institution and of specific actors such as Africa Uncensored that have built a reputation as credible media outlets practising investigative journalism by extension.

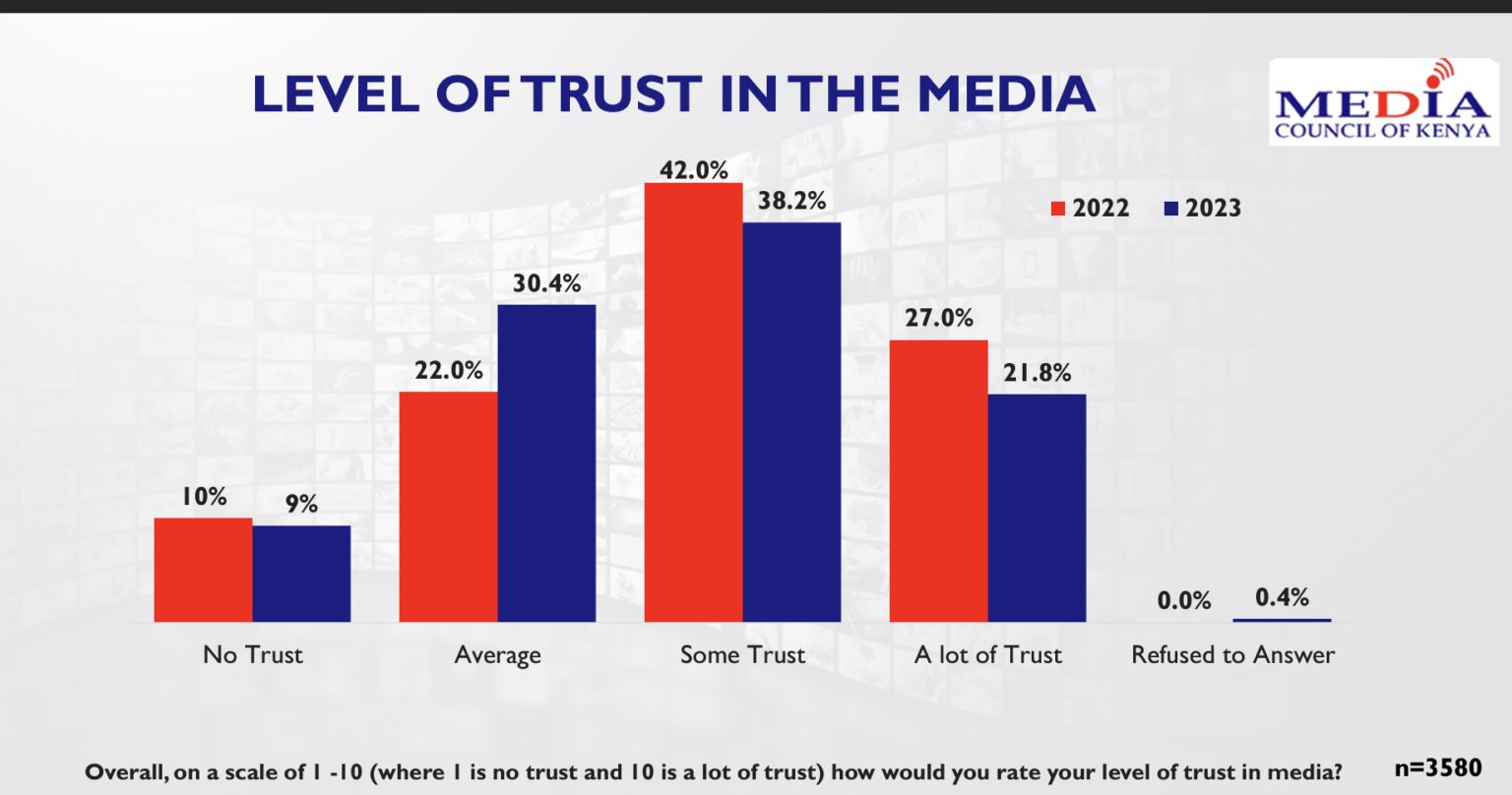

The Media Council’s State of the Media Report 2023 found that 38% of the surveyed respondents expressed some degree of trust in the media, compared to 42% in 2022, while 30% reported an average level of trust, up from 22% recorded in 2022.

Nine per cent of respondents stated they completely distrust the media, contrasting with a notable 22% who indicated a high level of trust in the media. In the 2022 survey, 10% had reported no trust in the media, while 27% had expressed a high level of trust.

Looking at the levels of trust across various media platforms, radio recorded the highest level of trust (at 33%), closely followed by television at 29%. Public distrust of the media overall increased between 2020 and 2022, as the proportion of those with little to no trust in media rose by 19% and 32% respectively.

What this data shows is that mainstream media is losing its audience’s trust, which could be a consequence of the attacks that Kenyan media outlets have experienced. They have repeatedly been accused of bias and false reporting when they cover issues of national importance, often as a way to dismiss unfavourable coverage.

The ‘fake news’ accusations are clearly meant to sow doubt and distrust in the media, effectively weaponising the work they do in order to coerce them to stay silent, and this tactic may be working.

Campaigns such as those attacking media outlets using altered images and false information are aimed at discrediting journalists and the truth they report. While this is not a new tactic, given previous attempts to shift the conversation on reproductive healthcare, fake fertilizer, and how the media covers religious figures, these campaigns often take the air out of important national conversations quickly and shift attention elsewhere.

The weaponization of social media in this way is a clear affront to press freedom, a fact not lost on actors such as Cambridge Analytica, who in the past have been able to develop and implement strategies to influence public perception. These constant attacks are a clear attempt to gag the media indirectly by making them, rather than the subjects they cover, the topic of conversation, and the resulting loss of trust is not just concerning, but a matter that should be treated with utmost concern.

Attacks of this nature can deter journalists from pursuing sensitive topics, especially given the high risk involved. Journalists play a crucial role in informing the public, holding power to account, and advocating for social change. However, this vital work often comes with significant risks. Those who investigate corruption, human rights abuses, and other sensitive issues may face threats, intimidation, and even violence.

Ultimately, what these attacks on the media do is can undermine public trust in the media. As shown in the data from the Media Council, Kenya is experiencing a decline in trust in media institutions and a rise in misinformation and disinformation. As a result, society as a whole suffers, as informed decision-making and civic engagement become more difficult.

When journalists are silenced or intimidated, the public loses access to crucial information and accountability mechanisms. This, compounded with the fear of reprisals, a parallel erosion of trust in the judiciary that is expected to intervene when the freedom of expression is threatened, and the continued weaponisation of social media is leading to self-censorship and a chilling effect on the practice of journalism as a whole.

Recommendations

Kenya’s media landscape has grown significantly since the last major existential crisis the industry faced, during the Moi regime from 1978 to 2002. The country has seen enhanced freedom of expression, improved access to information, and economic growth, as well as technological advancements such as increased access to the internet and a robust online ecosystem that has bolstered the constitutional right to freedom of expression.

The media industry has seen the rise of digital first and digital only platforms that have further diversified the landscape. These are the circumstances that led to the establishment of Africa Uncensored as an independent investigative media platform, and which have enabled it to grow and continue producing impactful content.

However, as has been previously described, there are a number of persistent challenges and setbacks that mean that Africa Uncensored’s story will continue to be the exception rather than the norm.

Africa Uncensored exists as an independent media house that conducts hard hitting investigative journalism, but it is very much an outlier. The case can be made for providing financial support and capacity-building programs for independent media organisations, as these are the ones that end up picking up the slack given the retreat of mainstream media away from these critical spaces where people consume and share information. The effective ‘flattening’ of the media landscape means that there are few diverse voices in the media space, and rather than promoting media pluralism and diversity, social media and online media platforms have led to the consolidation of media platforms, adoption of questionable funding methods, and a loss of talent in the newsrooms due to declining advertising revenue.

One way that the media and journalists in Kenya can support the protection of journalists and freedom of expression is by relying on regulators and regulatory bodies such as the Media Council of Kenya, which needs to be more robust in the way it agitates for the protection of journalists and media houses, and engaging with government in a way that ensures that they are able to call out these abuses in a meaningful way.

One such challenge is the lack of robust protections for journalists. This is crucial for ensuring a free and independent press. To safeguard journalists from harassment and intimidation, existing laws need to be enforced, such as the protection of whistleblowers, the implementation of access to information laws and laws that protect media practitioners and their work.

Further, law enforcement agencies should be trained on how to engage with and identify media practitioners in the field. As has been seen in the incidents shared, the police do not follow standard procedure when engaging with the media during situations of public unrest. As a result, these interactions put journalists at risk, and further compound the risk of misinformation and disinformation. There is a need to establish mechanisms for swift and impartial investigations into attacks on journalists, and journalists need to be trained on safety practices and how to carry their work out in the field. Media houses also need to provide training and support to their journalists, including legal aid and psychological counselling in the event that they are attacked in their line of work.

Given the attacks described on media organizations that involve the use of coordinated inauthentic behaviour, social media platforms need to have a good level of visibility on what conversations are genuine, and which ones are harmful and need to be addressed quickly once reported.

Lastly, there is also a real need to promote media and information literacy and online safety, especially considering how people now consume information primarily through digital platforms. This involves equipping individuals with the skills to critically evaluate information, identify misinformation, and to be able to discern whether the information they are consuming is genuine, thereby ensuring that they can make informed decisions and participate meaningfully in online and offline discourse.

Conclusion

The increasing prevalence of smear campaigns and disinformation targeting journalists and media actors in Kenya presents a significant threat to press freedom, the integrity of public discourse, and the overall democratic fabric of the country. As demonstrated by the case studies of Africa Uncensored’s investigative reporting, media practitioners in Kenya face coordinated attacks that seek to discredit their work, tarnish their reputations, and, in many cases, silence critical voices. These attacks are increasingly sophisticated, often leveraging social media platforms, coordinated inauthentic behaviour, and targeted harassment to distort public debate and deflect attention from issues of national importance.

The online smear campaigns, particularly those amplifying false narratives through fake accounts and fabricated content, not only target individual journalists but also aim to undermine the credibility of the media as an institution. By weaponizing disinformation, these campaigns sow distrust in the media, making it more difficult for the public to discern truth from falsehood. This contributes to a wider erosion of public trust in journalism, as reflected in declining levels of confidence in the media, as shown by the Media Council of Kenya’s 2024 report.

This trend is concerning, as it compromises the ability of the media to perform its core functions – holding power to account, informing the public, and facilitating civic engagement. The increase in online harassment, combined with real-world threats to journalists’ safety, creates an environment where fear and self-censorship can flourish. Journalists and media organizations are increasingly reluctant to pursue sensitive or controversial stories, knowing that they may face not only physical danger but also online campaigns that seek to delegitimize their work.

The disinformation campaigns also undermine public accountability, as they divert attention from critical issues such as corruption, human rights violations, and government accountability. By shifting the focus onto discrediting journalists and media houses, these campaigns distract from the substance of the stories and dilute the impact of investigative journalism. This not only harms the journalists directly involved but also deprives the public of valuable information that is essential for making informed decisions.

In light of these challenges, stakeholders in the media industry, including media houses, the government, and civil society must take proactive steps to protect journalists and strengthen the media ecosystem. Media regulators, such as the Media Council of Kenya, must play a more assertive role in advocating for the protection of journalists and addressing attacks on the media. There is a pressing need for stronger enforcement of existing laws that safeguard press freedom and protect journalists from harassment and intimidation. Additionally, media organizations must provide their journalists with adequate training and support to navigate the risks associated with investigative reporting, including legal aid, security training, and psychological support.

Furthermore, social media platforms must enhance their efforts to identify and mitigate coordinated inauthentic behaviour. By improving transparency and accountability in how disinformation campaigns are flagged and removed, these platforms can help to reduce the weaponization of online spaces. Equally, media literacy initiatives are crucial in empowering the public to critically assess the information they encounter online, thereby reducing the influence of misinformation and strengthening the role of the media as a pillar of democracy.

Ultimately, the protection of press freedom and the integrity of journalism in Kenya hinges on a collective effort to counter the growing tide of disinformation, safeguard journalists from harm, and promote an informed, engaged public. By reinforcing these protections and fostering a more resilient media environment, Africa Uncensored, and Kenyan media by extension, can continue to play a vital role in holding power accountable and driving social change.

This case study was commissioned by the IPI Africa program, with the support of the Government of Canada’s Office of Human Rights, Freedoms and Inclusion (OHRFI)

Top Stories Today