Finding solace in solitude: Forgotten elders of Mji Wa Huruma speak out

They say loneliness had pushed them to the home where they now feel abandoned by family.

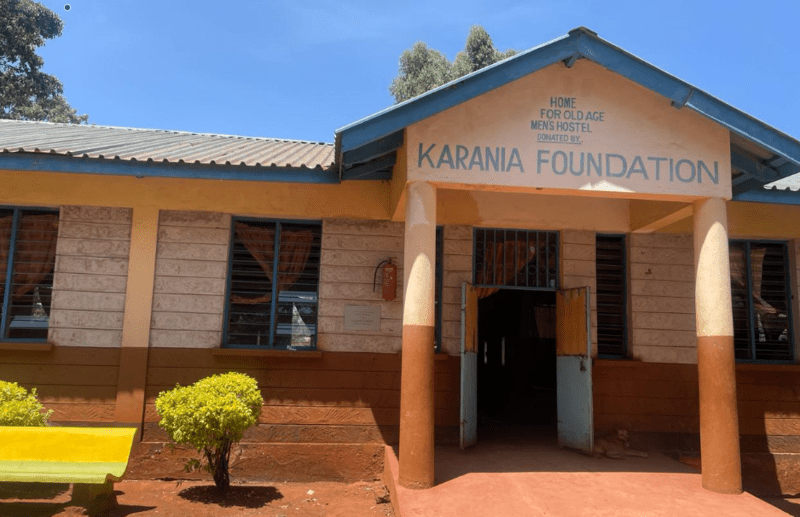

As you stroll along Nairobi's Kiambu Road, the quiet atmosphere is disrupted by the songs of the elderly at Mji Wa Huruma. This tranquil haven, nestled deep into the leafy suburbs, houses abandoned elders seeking solace from a society that seems to have forgotten them.

They say loneliness had pushed them to the home where they now feel abandoned. As you enter the gate, you are welcomed by their smiles, but they claim their hearts are yearning for more.

Located in the thick of Karura Forest and bordering Runda Estate, Mji Wa Huruma, crafted by the late Charles Rubia during the latter years of the 1960s, currently hosts 43 people: 16 women and 27 men.

The name Mji wa Huruma means home of mercy. The home for the elderly in this village was originally meant to be a rehabilitation centre for street children, but the elderly have since found their home here.

For eight years, Margaret, an 85-year-old, has called Mji Wa Huruma her home during her sunset years, where she has cultivated companionship among fellow residents who share a similar narrative of abandonment.

She narrates how she fractured her leg, and having no one to take care of her, she found herself at the home.

"One evening, as I tended to the farm, tragedy struck. I slipped and fell in our mud house, instantly fracturing my leg. The injury necessitated a six-month hospitalisation. After being discharged, I was afraid of being a burden to my family, and having no one to take care of me, I was compelled to seek refuge here, where I have since found peace and belonging," says Margaret.

Margaret explains that even though Mji Wa Huruma may appear destitute at first glance, shifting your gaze to the horizon will make you see a landscape teeming with selfless individuals who tirelessly care for them. She says that amidst the solitude, they find solace in the company of others who, like them, have experienced profound loneliness and have discovered comfort in each other's presence.

Neglected in hospital

Seated majestically, Francis Njoroge Mwaura, a 71-year-old gentleman, peruses a newspaper, his mind wandering back to the moments of despair that led him to his current abode.

"I first arrived here in 2013 after a stint at Kikuyu Hospital, where I was undergoing treatment for a leg injury. I remained at Mji Wa Huruma for five years until I had fully recovered. Afterwards, I spent two years living outside, but circumstances led me back here, this time after undergoing significant surgery at Kenyatta National Hospital," Mwaura says, tracing the arc of his journey through trials and tribulations.

Francis stayed at Kenyatta hospital for seven months with no one by his side. He walked through the cold hospital floors with no sense of identity.

Without any options, he went back to the place he calls home. He feels happy and content holding conversations with his roommates and reminiscing about their youths together.

"We wake up every day, pray together, and eat breakfast before everyone goes about their daily activities. Some would sew, others watch TV, while the rest engage in stories," Francis adds.

John Mwiti, a 78-year-old, speaks of the ache that accompanies the absence of family.

"We share meals and stories, yet I yearn for the sound of my grandchildren's laughter. This home doesn't replace the warmth of family. I wake up every day in the same mundane routine, reminiscing about the past and my family. I cannot remember everything vividly, but having no family around at this age is heartbreaking for me."

John parted ways with his children, with whom he says they never got along. He never saw his grandchildren or his family that often. He was a sickly man who spent his days at the hospital.

"I was always admitted to the hospital because of my bad eyesight, and somehow it became a burden to my family. They took care of me long enough that I cannot fault them for bailing out on me. I would have loved to see my grandsons once more before my time comes to pass," John says.

History of the home

The founder of the home for the elderly in Mji wa Huruma, the late Rubia, the first African mayor of Nairobi, immediately after independence saw the influx of abandoned elderly people all over the streets of Nairobi and sought to bring them together.

"Charles brought all the elderly people from the streets and brought them together in a single room in Bahati Estate. He provided them with all the basic needs they needed at that time. This land was donated to Nairobi city council by the white settlers who went back to their respective countries, and it became the home for the elderly around 1968," says Margaret Ndichu, the manager at Mji wa Huruma.

The home is strictly for the abandoned elders who have been found in the streets and hospitals on their own with no families. The clients are referred by different agencies and most include hospitals, and elders who have been treated and healed, but one year down the line, they are still stuck at the hospital with no one to call family and nowhere to call home.

County social workers also refer them to the home once they note that people within their jurisdiction are needy and abandoned. This also includes the police, area chiefs, different NGOs, and churches. They have to be 65 years old or older to be taken in, unless it is a special case.

While the state allocated Sh38.2 billion in the financial year 2022–23 to safeguard vulnerable groups like the elderly, the reality remains bleak, with many feeling neglected.

Many want society to reevaluate its values, and to ensure that the elderly are not abandoned to face the challenges of ageing alone.

Currently, the proportion of older persons (OPs) is estimated at 6 per cent of the country's total population. According to the 2019 National Census Report, the population of OPs in Kenya was 2,740,515 against a population of 47,564,296.

The elderly population lives in constant fear of disability and impairment, with a recorded 8 per cent suffering from mobility disability, 5 per cent from visual impairment, 3 per cent from cognition, 2.3 er cent from hearing, and 2.1 per cent from failed self-care.

Top Stories Today