Moi era torture survivors want Nyayo House chambers preserved as museum

Patrick Onyango's trauma was exacerbated by the torture of his fiancée who later took her own life.

Three decades ago, 66-year-old Patrick Onyango faced the wrath of Kenya’s second president, the late Daniel Arap Moi, for his opposition to the autocratic regime.

Speaking to The Guardian, Onyango said he spent 56 days in the dark, damp torture chambers of Nyayo House where he faced all sorts of cruelty.

More To Read

- Kenya’s constitutional gains at risk without ethical leadership and integrity - CJ Koome

- Cameroon opposition activist Anicet Ekane dies in custody; party demands accountability

- Kenya’s crackdown on activists spotlighted at AU rights summit

- Kenya on UN radar after ignoring letters on human rights abuses

- Tanzania denies Amnesty report linking government to enforced disappearances, torture

- Pressure mounts on Kenya to permit visit by UN special rapporteur

While vividly recalling how it started, he says, he was busy teaching in Kisumu when suddenly uniformed policemen came and ceased him and transported to him to Nairobi.

Being barely a student activist against the one-party rule in the early 1980s, he said he was detained in various cells before being blindfolded and taken to the notorious Nyayo House torture chambers.

Upon arrival at the chambers, Onyango said he was forced to undress and later beaten, and stabbed. Deprived of food and water for nearly two weeks, he said he resorted to drinking his own urine to survive.

“I was subjected to all kinds of torture – it was very cruel, very inhumane,” Onyango told The Guardian.

Onyango endured nearly two months in the torture chambers before being imprisoned for three years.

He said his trauma was exacerbated by the torture of his fiancée who later took her own life.

He recalls how guards brought his fiancee to the cell, forcing her to watch as they tortured and humiliated him. Afterwards, she was gang-raped in the next room. He found out after his release from prison that she had become pregnant from the abuse and had taken her own life.

He however said he has been mitigated by years of psychological support from a survivors' network.

“She was not part of [the activism for democracy] but paid the ultimate price, Onyango said adding, “The chiefs also sent word to my parents that I was dead; [they] were traumatised. My mum got hypertension after I was taken, and while I was fortunate enough to find her after my release, that’s what killed her.”

Stark reminder

“That is the reason why we want that place to be made a museum. It should be a reminder of what can happen when despotism takes centre stage in a country. We need to pass this story from one generation to another, to the point where we talk of ‘never again’.”

He noted that he and other survivors usually make annual visits to the cells every February to remember the atrocities.

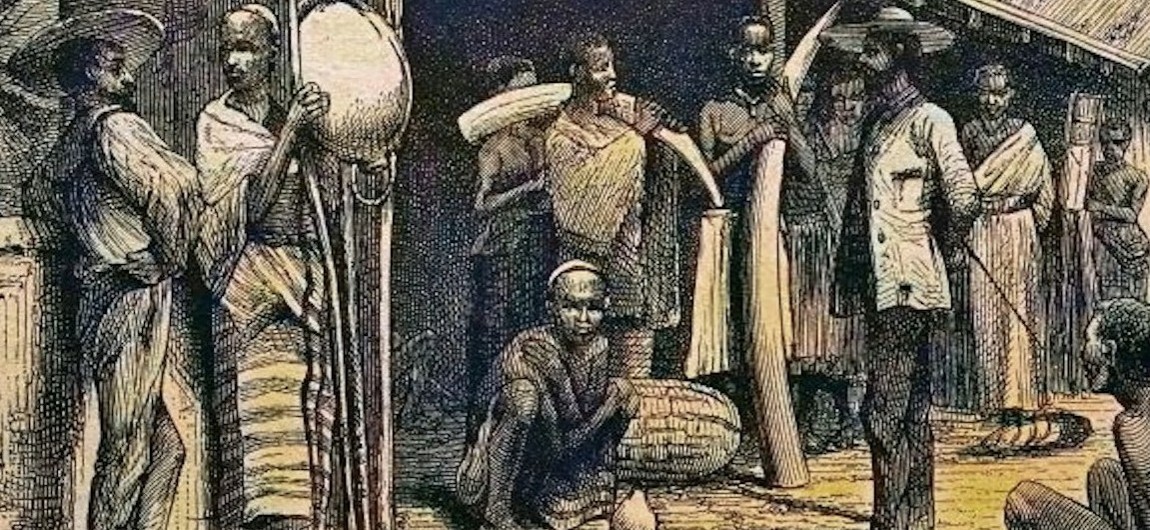

A section of the torture chambers underneath Nyayo House. (Photo: KHRC)

A section of the torture chambers underneath Nyayo House. (Photo: KHRC)

However, this part of Kenya’s history is scarcely taught in schools, and the cells, located in the basement of an immigration centre, are classified as a “protected area,” accessible only with special permission.

President Moi had intensified his crackdown on dissent, following a failed coup attempt by the armed forces in 1982. He introduced severe policing, human rights abuses, and laws to suppress political freedom.

Between 1986 and 1992, over 150 pro-democracy activists were detained and tortured in Nyayo House.

The Guardian notes that last month, survivors of Nyayo House torture, supported by the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) and the Law Society of Kenya (LSK), filed a lawsuit against the government, challenging the restrictions.

They demanded that the site be transformed into a national monument open to the public, as recommended by the country’s Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission in 2011.

No political goodwill

“There is no political goodwill from past and current governments to address historical state violations,” Martin Mavenjina, a senior adviser for transitional justice at KHRC, told The Guardian.

February 18th marks the anniversary of the opening of the Nyayo House torture chambers where illegal detention & torture of many Kenyans took place.

— KHRC (@thekhrc) February 18, 2021

We demand that the Nyayo torture chambers be converted to a human rights meuseum & be open 2 provide redress 4 toture victims. pic.twitter.com/PPHJPUoSqr

So far, the KHRC has documented over 100 torture lawsuits against the state, many of which have been successful, yet numerous victims have not received compensation.

The survivors have also detailed their harrowing experiences in the book titled, “We Lived to Tell”, describing how interrogators drove needles into their nails and inflicted severe genital torture.

Some detainees were killed, while others were coerced into confessions or imprisoned on charges of sedition and treason.

On July 7, 1990, a massive protest was organized in Nairobi’s Kamukunji Grounds, demanding political reforms and the end of the one-party rule.

Despite government warnings and the deployment of security forces to prevent the rally, thousands of Kenyans defied the authorities and gathered to voice their demands for change.

The government, however, responded with force, and the peaceful protest turned violent. Many demonstrators were arrested, including key leaders like Kenneth Matiba, Charles Rubia, Azimio leader Raila Odinga, and Martin Shikuku, who were detained without trial.

Over 20 people were reported to have died, thousands were left injured and others were arrested and charged.

The crackdown, however, did not quell the growing demand for democratic reforms. Instead, it galvanised the movement and drew international attention to Kenya's struggle for democracy.

The events of Saba Saba Day marked a turning point in Kenya's political landscape, as the brutality displayed by the government further fueled the demand for change. International pressure, combined with internal unrest, eventually forced President Moi to concede to some of the demands.

In 1991, Section 2A of the Kenyan Constitution was repealed, effectively ending the single-party rule and allowing for the formation of opposition parties. Kenya had its first multiparty elections in 1992 where about eight political parties participated.

The democratic space was also expanded as Kenyans were allowed to enjoy their freedom of speech and assembly, rights that were previously curtailed.

Top Stories Today