Study shows number of hungry, undernourished people in Kenya still high

The number of Kenyans who cannot afford a healthy diet has grown by about 22 per cent, from 35.1 million in 2017 to 42.8 million in 2022.

With just six years from the 2030 SDG targets 2.1 and 2.2 to end hunger and malnutrition, achieving these goals appears unlikely, especially in developing African countries, a study has shown.

Dubbed the 'The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024’, by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the study report highlights a troubling trend in the pursuit of the goal.

More To Read

- Rain turns deadly in Garissa, killing over 500 livestock

- Humanitarian agency appeals for Sh2.1 billion to aid 2.1 million Kenyans facing floods, drought

- Global food prices ease as East Africa slips deeper into hunger – report

- CS Kagwe says Kenya imports five billion eggs annually, urges farmers to boost local production

- FAO warns of declining youth jobs in agrifood systems despite global demand

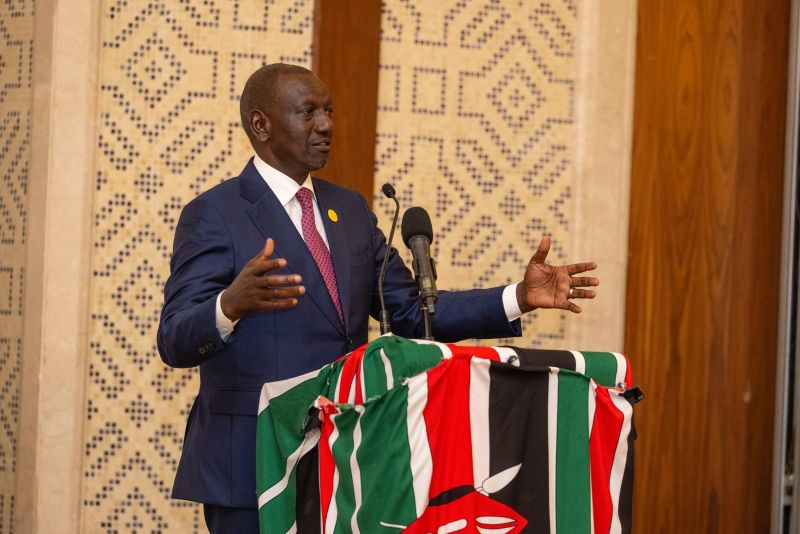

- Ruto declares food security key to Kenya’s sovereignty

"Hunger and food insecurity trends are not yet moving in the right direction to end the crisis by 2030," the report reads.

"The indicators of progress towards nutrition targets similarly show that the world is not on track to eliminate all forms of malnutrition. Billions of people still lack access to nutritious, safe and sufficient food."

In Kenya, the study reveals that the number of hungry and undernourished people has remained stubbornly high despite recent efforts and commitments to end the crisis.

It attributes the prevailing landscape to factors such as climate change, conflict, and economic instability that continue to undermine food systems, making it increasingly difficult for vulnerable populations to secure their basic nutritional needs.

Healthy diet cost

The study reveals that the cost of a healthy diet in Kenya has consequently risen by about 27 per cent in the past five years to 2022.

In other words, the cost of a healthy diet per person per day stood at $3.54 (Sh457 at the current exchange rate) as of 2022, up from $2.79 (Sh360) in 2017.

Consequently, the level of unaffordability of a healthy diet among Kenyans has increased significantly in terms of population size.

FAO says the percentage of the Kenyan population unable to afford a healthy diet has risen steadily over the past five years, climbing from 71.7 per cent in 2017 to 79.2 per cent in 2022.

In absolute numbers, the number of Kenyans who cannot afford a healthy diet has grown by about 22 per cent, from 35.1 million in 2017 to 42.8 million in 2022.

On the other hand, generally, the number of Kenyans facing hunger has also reportedly been on the rise over the years.

For instance, data by the international firm, Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), which specialises in overview research and analysis towards improving food security and nutrition, says its latest data shows a likely unprecedented deterioration in Kenya's food security situation.

"During the projection period (October 2024-January 2025), the food security situation is likely to deteriorate further due to the high likelihood of severe rainfall deficits during the (October-November-December), which may result in below-average harvests, especially across the northern and eastern Kenya (ASALs)," IPC says in its latest update.

"Approximately, 1.7 million people (11 per cent of the population analysed) are classified in IPC Phase 3 or above, including about 98,000 people classified in Phase 4 (emergency) and 1.6 million in Phase 3 (crisis)."

In Africa, FAO says 58.0 per cent of the population was moderately or severely food insecure in 2023, and 21.6 per cent faced severe food insecurity, although the differences between sub-regions were notable.

Middle Africa had the highest prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity (77.7 per cent, or 157 million people), making it the sub-region with the highest level in the world.

The region is made up of Angola, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, DRC, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.

It is followed by Eastern Africa, made up of countries like Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania (64.5 per cent, or 313 million people) and Western Africa; comprising Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo (61.4 per cent, or 270 million people).

"One-quarter of the population of Southern Africa (17.3 million people) and more than one-third of Northern Africans (89.4 million people) were affected by moderate or severe food insecurity in 2023," FAO notes.

"From 2022 to 2023, the proportion of the population experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity increased at least marginally in most sub-regions of Africa, especially in Southern Africa, where it increased by 2.1 percentage points."

Policy action

With the reverse in progress and the persistently high levels of hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition, the organisation is now emphasising the need for countries to strive to attain the scale of actions needed, sufficient levels of and equal access to financing to address the crisis.

It says meeting SDG Targets 2.1 and 2.2 requires increased and more cost-effective financing, but there is currently no clear picture of the financing for food security and nutrition, neither that available nor that additionally needed for meeting these targets.

"Not bridging this gap will result in social, economic and environmental consequences requiring solutions that will also cost several trillions," FAO says.

It adds that innovative, inclusive and equitable solutions are needed to scale up financing for food security and nutrition in countries with high levels of hunger and malnutrition.

"However, many low- and middle-income countries face significant constraints in accessing affordable financing flows."

FAO, therefore, advises that for countries with limited ability to access financing flows, grants and concessional loans are the most suitable options, while countries with moderate ability can increase domestic tax revenues, linking taxation to food security and nutrition outcomes.

Nevertheless, the organisation notes that the current food security and nutrition financing architecture is highly fragmented and needs a shift from a siloed approach to a more holistic perspective.

It reiterates that enhanced coordination among actors is needed on what is essential considering national and local policy priorities.

To that aim, transparency and harmonising data collection are crucial for improving coordination and targeting financing effectively, it adds in part.

"Donors and other international actors need to increase their risk tolerance and be more involved in de-risking activities, while governments must fill the gaps not addressed by private commercial actors by investing in public goods, reducing corruption and tax evasion, increasing food security and nutrition expenditure and considering repurposing policy support."

Top Stories Today