COP29 aftermath: Youth call for manageable goals to meet Africa's climate needs

Even though Africa contributes little to global emissions, it is already facing severe effects of climate change, like more droughts, floods, and rising temperatures.

Developed nations, despite being the main cause of climate change, continue to disadvantage Africa and other developing nations, even though these regions suffer the most from its effects. These countries still rely on wealthier nations for help with adaptation and mitigation, leaving them in a weak position.

Various meetings of the annual Conference of the Parties (COP) – the supreme decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – have been held where world leaders meet to negotiate and discuss ways to reduce the impact of climate change.

More To Read

- African women key to fighting climate change – these are the green skills they will need

- Our oceans are in trouble: how to move beyond the outrage and start taking real action

- Kenya gets Sh16.4 billion loan to tackle rural poverty, climate woes

- Tide of change: Coastal women demand bigger role in blue economy

- Kenya unveils 2024–2030 disaster risk strategy to protect lives and boost resilience

- Kenya cuts environment budget to Sh103.8 billion despite climate change pressures

However, Africa has received very little support from these annual meetings, with many experts and negotiators feeling frustrated over time. This year's COP29, held in Baku, Azerbaijan, brought no significant change.

African leaders have been asking for fairness and support to fight climate change, but the lack of resources keeps them dependent on richer countries, who have been slow to provide the necessary help. This unwillingness makes it even harder for Africa and other developing nations to effectively address climate challenges.

Stalled negotiations and unclear commitments marked COP29, leaving Africa's climate needs unmet. For instance, Kenya presented its ambitious climate goals, focusing on adapting to climate impacts, promoting gender equality, and ensuring sustainable development for its people. However, the key question remained: how much financial support would actually be provided to help achieve these goals?

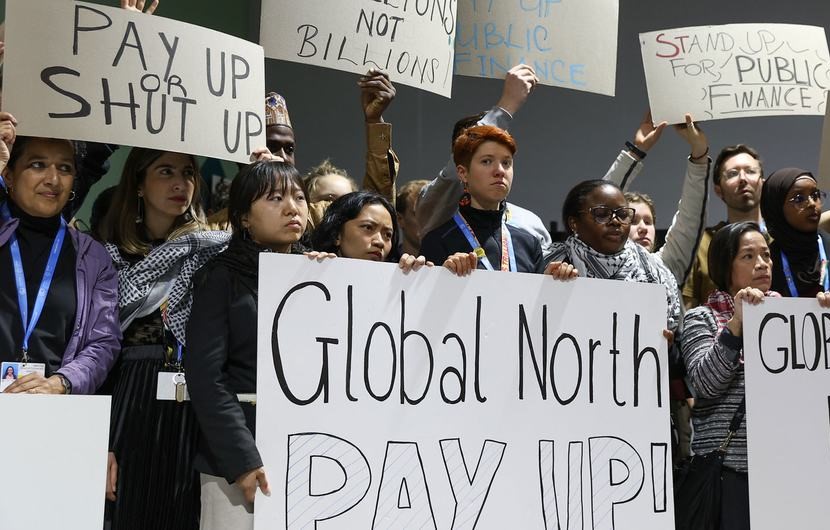

Civil society actors at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, advocate for climate financing initiatives. (Photo: UNFCCC/Kiara Worth)

Civil society actors at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, advocate for climate financing initiatives. (Photo: UNFCCC/Kiara Worth)

Kenya and other African countries have been pushing for climate funding to help with adaptation and cover losses from climate impacts, expecting a budget of $1.3 trillion. But at COP29, developing nations only agreed to raise $300 billion, much less than what Africa and others had asked for.

Even though Africa contributes little to global emissions, it is already facing severe effects of climate change, like more droughts, floods, and rising temperatures.

The continent urgently needs money to cope with these impacts. Wealthy countries in the Global North, which have caused most of the emissions, have promised help, but many have failed to keep their promises and continue to make new ones without following through.

After COP29, on Thursday, December 5th, young people, women, and indigenous groups gathered at the Young Women Christian Association (YWCA) in partnership with Hivos. They met to discuss the conference's outcomes and reflect on the successes and challenges.

Earlier in the year, they had presented a proposal to the climate committee, outlining the changes they wanted to see.

While some participants acknowledged positive outcomes, most expressed frustration with the process. Others had mixed reactions, recognising some wins but stressing that much more needs to be done to ensure developing countries, especially in Africa, receive the support they urgently need.

Merline Achoki, a lead negotiator at COP29, highlighted one of the key agreements: the development of indicators for climate adaptation strategies.

These indicators are meant to help countries track how well they are adapting to climate change, ensuring that efforts are effective and that resources are being used appropriately.

Activists hold a silent protest against the draft agreement, during the COP29 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan November 22, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Murad Sezer)

Activists hold a silent protest against the draft agreement, during the COP29 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan November 22, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Murad Sezer)

Manageable goals

The goal is to create a set of globally applicable, simple indicators that can be used by countries around the world, no more than 100 in total. These indicators will help measure progress, assess how well adaptation plans are being implemented, and ensure accountability, so countries can report on their efforts transparently.

"Countries agree that we need a set of manageable goals, no more than 100 indicators that are globally applicable and can be implemented," Achoki said.

These indicators will allow countries to track the resources allocated for climate action and measure the impact of those resources, making sure that the efforts to adapt to climate change are not only planned but are actually being carried out effectively.

Salome Owunda, a gender specialist, celebrated Kenya's victory in extending the Lima Work Programme for another 10 years.

The Lima Work Programme on Gender (LWPG) is an action plan that aims to advance gender balance and gender-responsive climate action. The LWPG was established in 2014 by UNFCCC.

This programme ensures that gender is considered in climate action, making sure that policies address the different needs of men and women.

Environment CS Aden Duale speaks during climate talks in Baku, Azerbaijan, focused on November 12, 2024. (Photo: Ministry of Environment)

Environment CS Aden Duale speaks during climate talks in Baku, Azerbaijan, focused on November 12, 2024. (Photo: Ministry of Environment)

Gender inclusivity

Owunda emphasised that involving both men and women in climate action can create more effective solutions, as it leads to better decision-making and more holistic approaches. She also stressed the importance of planning climate projects with inclusivity in mind, ensuring that the needs of all community members — regardless of gender, age, or other factors — are taken into account.

"Gender transformation is important in changing norms to influence holistic mitigation action. If both men and women work together, it becomes much more impactful," said Owunda.

She said climate policies should be developed in a way that considers the broader societal impacts, making sure that no one is left behind.

"When thinking of a project, we should have a perspective that everything and everyone in the community will be impacted," she said.

This approach ensures that climate actions are designed to benefit the whole community, with a focus on those who are most vulnerable.

The Lima Work Programme on gender was extended for another decade at COP29, with a new gender action plan expected to be adopted in June 2024. This is a major step forward for developing countries, as it encourages them to continue integrating gender considerations into their climate strategies.

Owunda also emphasised the need for gender-responsive climate finance — funding that specifically addresses the needs of both men and women.

Without such financing, it will be difficult to implement climate projects effectively.

"We need gender-responsive financing because, without it, you can't implement the projects," she said.

In addition to this, Owunda pointed out that men and boys should also be involved in gender-responsive climate initiatives.

"Men and boys can be beneficiaries too, and they should be engaged as partners in gender-responsive action," she explained.

By including men and boys in these efforts, the overall impact of climate action can be greater, as they too have an important role to play in combating climate change.

World leaders attending the United Nations climate change conference, COP29, pose for a photo in Baku, Azerbaijan on November 12, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Murad Sezer)

World leaders attending the United Nations climate change conference, COP29, pose for a photo in Baku, Azerbaijan on November 12, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Murad Sezer)

People with disabilities

Dennis Mwanzia, a person with a disability from Kajiado, highlighted the importance of ensuring continued representation for people with disabilities in climate discussions, particularly at COP.

He argued that those who are most affected by climate change, including people with disabilities, should have a stronger voice in negotiations. He emphasised that people with disabilities are often overlooked in climate action discussions, and solutions must be tailored to the specific needs of these communities.

"It's my desire that more persons with disabilities would be allowed to represent themselves in negotiations because they are better able to articulate their challenges, as they are among the people most affected by these issues," said Mwanzia.

He said that many of the people representing the disability community at COP are not actually disabled themselves, which can lead to a lack of understanding about the real challenges faced by disabled people. He urged that solutions must be designed with the input of those who are directly impacted.

Attendees sit in the negotiation room during the COP29 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan November 23, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov)

Attendees sit in the negotiation room during the COP29 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan November 23, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov)

A win for the youth

Benjamin Okilo, a gender advocate and negotiator, highlighted a major win for young people at COP29, celebrating the improved representation of the youth at the conference.

He noted that youth voices were being amplified more than in previous years.

"To have young people articulate their challenges and amplify their voices at COP29 is a major win for the youth, and we want more representation," Benjamin said. He emphasized that young people are key to driving long-term climate action, and their inclusion in discussions is essential for shaping a more sustainable future.

Okilo also noted that COP29 saw greater involvement of indigenous peoples, especially women, in the discussions around Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) — which are the climate action plans submitted by each country.

"The adoption of indigenous peoples, especially women, who are affected in many ways due to access to health and other issues, was included in the NDCs, so they can raise their issues," he said.

This inclusion is important, as indigenous communities are often among the most vulnerable to climate change, and their voices need to be heard in policy-making.

Protestors during the COP29 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan November 23, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov)

Protestors during the COP29 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan November 23, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov)

Loss and damage fund

One of the major outcomes was the launch of the Fund for Loss and Damage, which will begin distributing funds in 2025. This fund is a significant win for developing countries, especially small island nations, least-developed countries, and African nations that are already facing the devastating effects of climate change. However, many criticised the amount of funding as too small and the timeline as too slow.

They also raised concerns about the potential misuse of carbon markets, which are designed to allow countries to offset their emissions by investing in environmental projects.

Carbon markets are systems where countries or companies can buy and sell carbon credits. These credits represent a certain amount of carbon dioxide emissions that have been reduced or avoided.

The idea is to encourage businesses and countries to reduce their emissions by giving them a way to earn money by cutting down on pollution. If a company produces less carbon than allowed, it can sell its extra credits to another company that needs them.

Prime Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi (centre) with Environment CS Aden Duale (second from left), Environment PS Festus Ng'eno (left) with delegates at COP29 on November 12, 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Handout)

Prime Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi (centre) with Environment CS Aden Duale (second from left), Environment PS Festus Ng'eno (left) with delegates at COP29 on November 12, 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Handout)

The Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice warned that carbon offset schemes, which are often used by major polluters to meet their climate commitments, have not proven effective at reducing emissions. These schemes can also harm vulnerable communities and ecosystems.

"Carbon offset schemes have been shown to fail at reducing emissions while harming frontline communities and ecosystems," they said.

Such schemes can lead to land grabs, deny indigenous peoples access to forests, and result in human rights violations, gender violence, and biodiversity loss.

While COP29 made some important strides, many African and developing nations feel their needs were still not fully addressed.

The conference highlighted the need for more inclusive, gender-sensitive, and community-driven climate action, but the question of adequate funding and real accountability remains.

Developing nations will continue to push for stronger commitments, and the fight for climate justice will go on.

Top Stories Today