Mwongela Kioko: A Nairobi street child’s audacity to beat the odds

His story is one of resilience and offers hope to other members of Nairobi’s street families, whose lives are too often marked by suffering and despair.

Aga Khan Walk, in the heart of the city’s Central Business District, is always busy with human traffic. Its central location makes it a popular meeting point.

Some residents wait for friends, others relax as they pass the time, while many are glued to their smartphones to enjoy the free street internet installed by the government.

More To Read

- Insecurity hits Nairobi CBD as gangs mug, drug and rob residents in broad daylight

- Nairobi book vendors decry City Hall's backstreet relocation directive

- City MCA calls for streetlight policy to address growing insecurity

- Equality Commission condemns Geoffrey Mosiria for 'exploiting vulnerable street child', calls for action

- Government sued for blocking CBD roads during protests, lobby demands removal of barricades

- Nairobi cracks down on littering and spitting in CBD as new dustbins rolled out

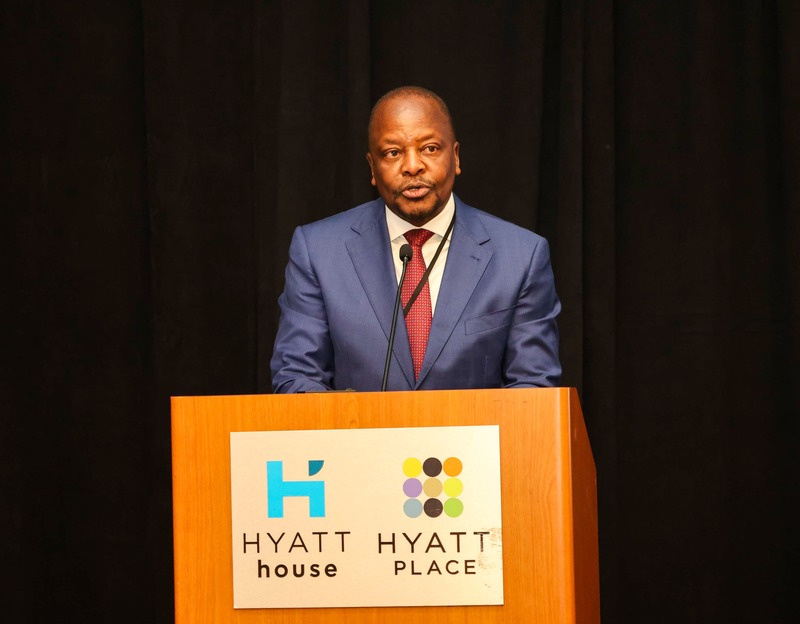

It was here that I noticed Boniface Mwongela Kioko moving purposefully among seated residents, carrying a container of shoe polish and brushes.

At first glance, he could have been just another hawker trying to eke out a living in the city long nicknamed shamba la mawe, a euphemism for the harsh struggles of urban survival. But what stood out was his youthfulness and determination.

When The Eastleigh Voice sat down with Kioko, his was a story of pain, hope, and resilience.

“I was a street child before I began hustling to feed myself. I have even spent time in prison,” he began.

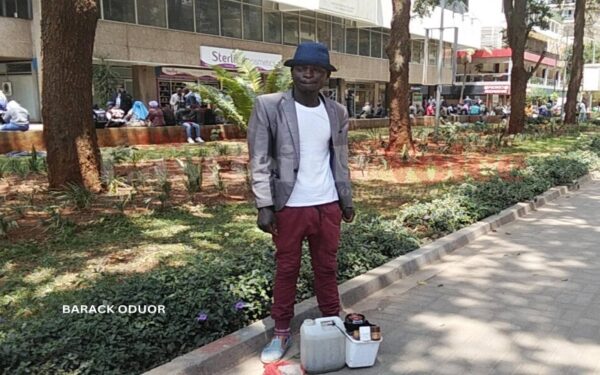

Mwongela Kioko. (Photo: Barack Oduor)

Mwongela Kioko. (Photo: Barack Oduor)

Born 25 years ago in Makueni, Kioko lost his mother at a young age and fled home following irreconcilable family differences with his father. One of six siblings, he ended up on the streets of Nakuru after dropping out of school.

“To survive, I did menial jobs, working in restaurants, washing dishes, even doing laundry for a few shillings. I remember working as a farmhand in Kinangop. It was back-breaking work, harder than what I used to do in Nakuru, like selling charcoal by the roadside,” he recalled.

His darkest moment came in Kerugoya, Kirinyaga County, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Living with a woman who had taken him in, he was accused of defiling her two-year-old child.

“When we fell out, she accused me, and I was arrested. I stayed in remand for nearly four years,” he narrated.

Mwongela Kioko. (Photo: Barack Oduor)

Mwongela Kioko. (Photo: Barack Oduor)

Prison life was a nightmare: long nights, no legal representation and endless delays in court. Eventually, the case collapsed for lack of evidence.

“Being in remand was barbaric. There was never enough food, and the suffering was immense. What saved me was that the case was dismissed, as I knew I was innocent,” he said.

In early 2025, Kioko moved to Nairobi, where he began hawking roasted groundnuts. Though profitable at first, frequent arrests and harassment by city inspectorate officers made the venture unsustainable.

“To sell food in the city, you need clearance licences, and without them, hawkers are constantly in trouble,” he explained. After losing stock in a raid, he decided to switch to mobile shoe-shining.

“Mobile shoe-shining works for me because I go to the customers instead of waiting for them. Every day I start from Muthurwa Market and walk across the city looking for clients,” said Kioko.

Today, he makes up to Sh1,000 a day, enough to pay his rent and keep his business running.

Top Stories Today