Families find safety in Arab 6 camp amid uncertainty in Sudan

Child-friendly spaces provide an opportunity to raise awareness around risks to children as well as somewhere that information can be provided about available services and support.

“There was a lot of gunfire around where I live,” says 17-year-old Remah as she recalls the wave of violence that swept Al Jazirah state in Sudan in late 2024.

“I was really scared. We didn’t know where we were going. We didn’t have a plan. But my family decided we had to leave immediately.”

More To Read

- Refugee youth rewrite their future through film in Dadaab

- Over 30 million people in Sudan in need of humanitarian assistance: UN agencies

- Sudan among countries facing widespread mine and explosive contamination – UN report

- Suicide drones struck Sudan's capital Khartoum, forcing airport closure amid escalating attacks

- IOM urges immediate aid as Khartoum returnees surpass one million

- RSF drone attacks hit Khartoum Airport ahead of planned reopening

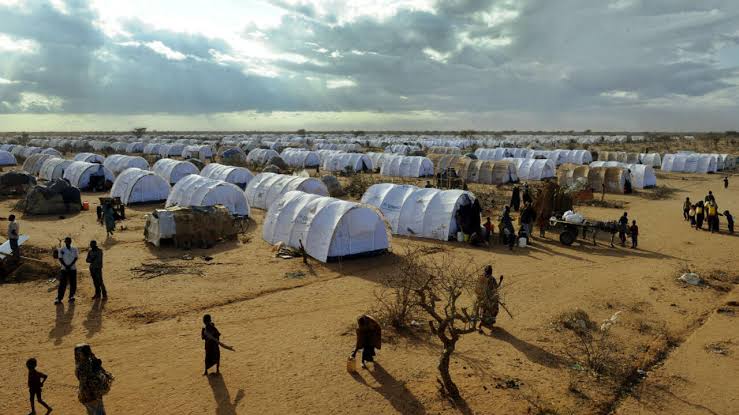

After fleeing on foot, Remah and her family eventually arrived at the recently established Arab 6 camp in Kassala state, eastern Sudan. The camp is home to an estimated 1,600 families, many of whom walked for days to get here as they fled spiralling conflict back home.

Remah is sitting on the floor of a child-friendly space, drawing a young woman with a butterfly fluttering towards her. She sketches the outline of the face and hair quickly, clutching some coloured pencils as she talks. She’s remarkably focused considering the boisterous atmosphere in the tent.

“I’ve liked drawing since I was little,” she says. “I like drawing traditional dresses.”

Chaos, comfort

Salawa, 17, also likes drawing but gets her inspiration from anime characters she saw on TV before she fled her home with her father and brothers. “But there isn’t any TV here,” she says.

One of Salawa’s friends was killed in the fighting and her family house was destroyed. “I don’t know what happened to some of my family,” she says.

Salawa has been at Arab 6 for almost three months, but she isn’t sure how long her family will stay.

“I feel sad. I don’t know where we’ll go next,” she says. “I miss my home and my friends and my cats.”

But she adds that she has made two new friends since she arrived at the site and is happy that she has been able to attend the child-friendly space because she gets a chance to spend some time with people her age.

“And I really like the time we get to draw,” she adds.

Giving children somewhere to play allows them to work through feelings such as pain, fear or the loss of a loved one while being able to still act like a child. Play also gives children a way to express things they are struggling with that they might not yet have the words to fully explain.

Raising awareness

Child-friendly spaces also provide an opportunity to raise awareness around risks to children as well as somewhere that information can be provided about available services and support. At the spaces in Arab 6, there are two social workers and two psychologists on hand to offer support.

Abdullah has been a child-friendly space coordinator here with UNICEF partner CDF since November and has already noticed a difference among the children attending the spaces.

“We’re gradually seeing a positive change in the way the children interact with each other,” Abdullah says. “At first it was difficult with children from so many backgrounds. But now they’re becoming friends.”

One of the most visible examples of that change? What the children are drawing.

“When the children first arrived at the site, most of them were drawing guns, planes, those things,” he says. Now they rarely do.

Out of school

An estimated 17 million children in Sudan are out of school due to the ongoing conflict, exacerbating an already dire learning crisis. Hundreds of schools across the country are serving as shelters for displaced people, further disrupting the education system.

As part of its efforts to help displaced children keep learning, UNICEF-supported learning centres in Arab 6 have enrolled almost 1,600 children in classes. Children attend classes six days a week, typically starting at 7 am, and study the national curriculum.

Taha, 13, has been in Arab 6 since November. He says he has been out of school since the war started but has been excited to be able to take classes at the learning space.

“I like being able to take classes here because I really missed studying,” he says. In fact, he’s taking tests in Arabic and maths tomorrow.

“I really like studying. I even read and study on my days off,” Taha says.

Arabic is his favourite subject, but he says doesn’t like studying English. “It’s so difficult!” he adds with a smile.

There are currently 20 teachers at Arab 6 – 13 women and 7 men – all of whom are themselves internally displaced. UNICEF has provided recreational kits and learning materials for the learning spaces.

Formal and non-formal education

Across the country, UNICEF has worked with partners to provide more than 2.3 million children with formal and non-formal education opportunities. But even as some children have started to return to class, millions more remain out of school.

Access to education is about more than the right to learn – schools protect children from physical dangers around them, including abuse and exploitation.

They can also provide children with lifesaving food, water and healthcare while giving children stability and structure to help them cope with the trauma they are experiencing. Without access to schools, the country’s current learning crisis will become a generational catastrophe.

Taha says being back in classes has given him a chance to make new friends. “I’ve made a lot since I got here,” he says. “They come from different villages.”

But learning is also giving him a chance once again to dream of a better future, and one day to have his own career – one where he can help those around him.

“I want to be a doctor,” Taha says. “I want to make sure people get treatment and help people who need it.”

Top Stories Today