MPs reject proposed media code, cite threats to press freedom

According to Information, Communication and Digital Economy Cabinet Secretary William Kabogo, the proposal was developed with input from key media stakeholders, including owners and newsroom managers.

The introduction of a new media code by the government has sparked strong opposition from Members of Parliament, who argue the proposed rules pose a serious threat to press freedom and could cripple independent journalism in the country.

The government is seeking to replace the current code, operational for 13 years, with a stricter framework that MPs say veers dangerously into censorship.

More To Read

- Four CSs in fresh legal battle over Sh50 e-Citizen fee

- Uproar as CS Duale clashes with reporter over SHA claims

- High Court stops swearing-in of Media Council board members appointed by CS Kabogo

- ICT CS William Kabogo taken to task for failing marginalised areas on connectivity

- Kenya adopts new media code, ushering in stricter AI and child protection rules

- Media stakeholders urge MPs to fast-track approval of new media code of conduct 2025

According to Information, Communication and Digital Economy Cabinet Secretary William Kabogo, the proposal was developed with input from key media stakeholders, including owners and newsroom managers.

“This is a document that we fully own with the media. They were part of the formulation of the rules,” Kabogo told the National Assembly’s Committee on Delegated Legislation.

However, the committee, chaired by Ainabkoi MP Samuel Chepkonga, pushed back, insisting that collaboration with the media does not override the legal protections guaranteed under the Constitution.

“The participation of the media in the generation of the code should not take away your responsibility to abide by the law,” said Chepkonga.

The proposed Code of Conduct for Media Practice 2025 seeks to repeal the existing regulations and expand the number of clauses from 26 to 32. One of the most contentious clauses redefines what constitutes a “claim.”

“Claim means any statement, assertion, or representation of fact, opinion, or belief presented as true in a publication, whether in written, oral, or digital form, that is subject to verification unless derived from a privileged or legally protected document where verification is impracticable,” the draft reads.

MPs questioned the legal basis for such terminology.

“The word ‘claim’ has been assigned a different meaning from the one we know. What provision of the law defines this?” Kilgoris MP Julius Sunkuli posed.

Efforts by Media Council of Kenya CEO David Omwoyo to explain that “protected document” includes court records or official documents legally obtained failed to persuade the committee. Members insisted the term was not grounded in any existing law.

Kathiani MP Robert Mbui accused the government of using the code to covertly suppress press freedom.

“What new ideas are you introducing by repealing the existing code? These are attempts to muzzle the media in subtle ways,” he said, while referencing clauses 4(g) and 4(h).

Clause 4(g) states that, “A journalist shall verify the accuracy of statements and allegations made in public spaces before publication.”

Sub-clause (h) adds that claims must be verified “except where such claims are drawn from privileged or otherwise legally protected documents and their verification is impracticable.”

Chepkonga warned the ICT ministry that the proposed rules carry legal inconsistencies that must be addressed before the committee issues a final recommendation, including the possibility of revoking the code entirely.

“Your Act states that the CS, with the recommendations of MCK, may amend the code. You have not shown evidence supporting this,” he said, referring to Section 45(2) of the Media Council of Kenya Act.

Kigumo MP Joseph Munyoro warned that the verification requirements could hinder real-time reporting and kill the media’s watchdog role.

“This is killing the opinion of a news source. If I have my opinion, why should the media be liable for it? It is akin to banning live broadcasts. Again, what are verifiable sources? If you are on a live show, where does the media get the time to verify what is said?” he posed.

The new code also compels journalists to make reasonable efforts to seek comment from individuals adversely mentioned in editorial content, except where the reference appears in opinion or commentary pieces and the underlying facts are already public.

“A person subject to this Act shall present all material sides of an issue being published fairly and impartially, preserve evidence of unsuccessful attempts to contact persons adversely mentioned in a publication, and clearly distinguish between comment, conjecture, and fact in all reporting,” the code states.

Additional requirements call for headlines to accurately reflect the content and context of stories. Where allegations appear in headlines, they must either name the source or be enclosed in quotation marks.

The draft also calls on newsrooms to avoid deliberate exclusion of any group in news coverage and to remain sensitive to cultural and contextual differences.

In terms of editorial integrity, clause 8(f) demands full disclosure of sponsored editorial content, including identification of the sponsor, and clear separation from independent journalism.

“Before recording or broadcasting a conversation, inform any party to the call of the intent to do so, unless public interest justifies otherwise,” the code adds, while also restricting photography or recording of people in private spaces without their knowledge.

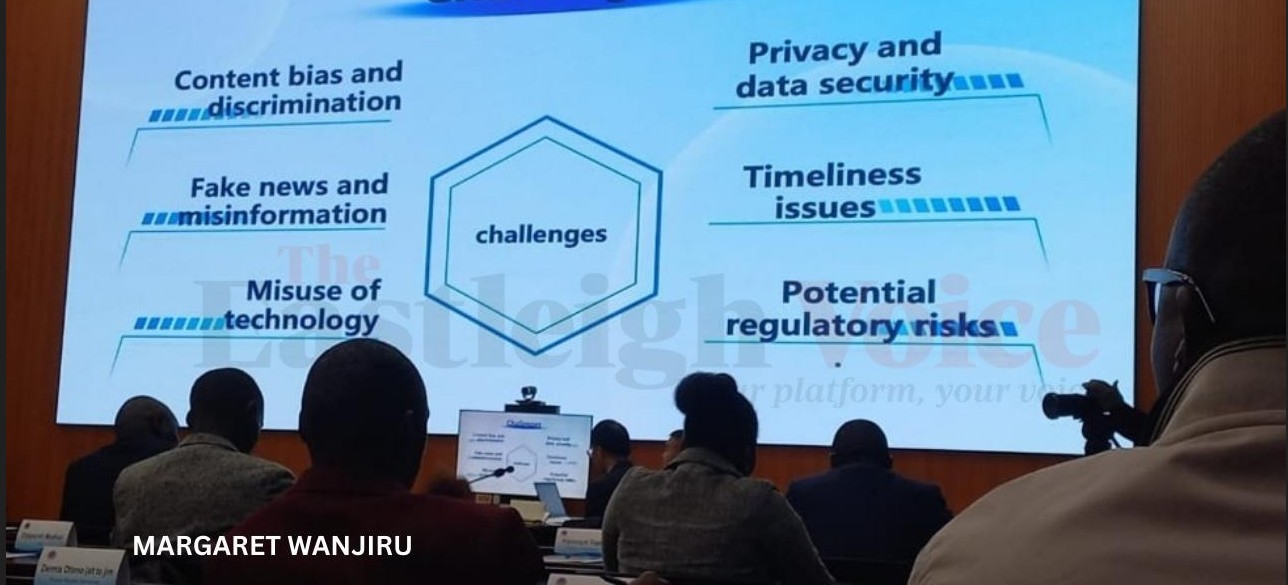

A new section addresses emerging technologies and content creation, requiring disclosure whenever artificial intelligence has been used in producing or modifying editorial content. Such material must undergo review and approval by human editors before publication.

The proposed amendments also introduce live broadcast delays and strict penalties for violations.

Section 11 of the draft law provides that, “A media enterprise shall incorporate a minimum seven-second delay in live broadcasts to prevent the unintended publication of material that violates this code.”

Media Council of Kenya CEO David Omwoyo defended the clause, stating, “Seven seconds is an international standard. In war reporting where the military is involved, 21 seconds to a minute is the minimum. It allows time for the editor to make a decision.”

The proposed law also holds platforms accountable for content circulated through them.

“A person subject to this Act shall be responsible for hate speech published or disseminated on their platform.”

Violations will attract hefty penalties. Individuals found guilty will face a fine ranging between Sh200,000 and Sh1 million, or imprisonment for a term between six months and one year. Media owners and managers will also be personally liable under similar terms.

As debate over the code intensifies, MPs have warned that unless major revisions are made to align with constitutional guarantees, they will push for its revocation.

Top Stories Today