Moroccan Ties: How Kenya quietly abandoned the Sahrawi cause

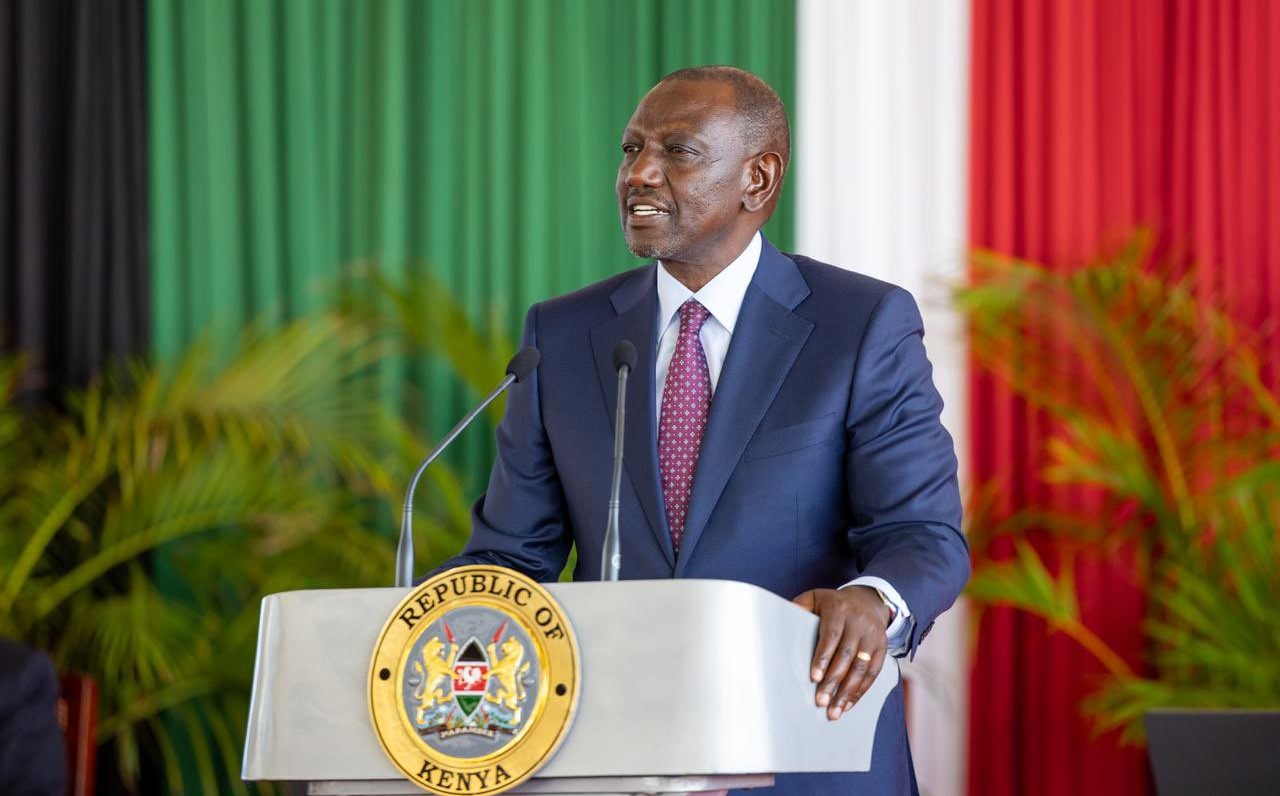

This article traces the chronological and political moments behind Nairobi's dramatic turn on the Sahrawi cause—a founding member of the African Union—and how a seemingly quiet 2021 meeting between then-Deputy President William Ruto and Morocco's former envoy to Kenya, Mokhtar Ghambou, helped reshape Kenya's foreign policy trajectory.

For decades, Kenya stood firmly in support of Western Sahara's pursuit of statehood, aligning itself with Pan-African ideals and the right to self-determination. That legacy came to a quiet but seismic shift last week, when Kenya officially opened its first embassy in Rabat and named an inaugural ambassador to Morocco, effectively throwing the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) under the bus.

The timing could not have been more symbolic. The announcement came during the United Nations' week of solidarity with Non-Self-Governing Territories (NSGT), observed between May 25–31. It was also the same week Kenya's top diplomat, Prime Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi, declared Morocco's autonomy plan "the only credible and realistic solution" to the Western Sahara conflict during his visit to Rabat.

More To Read

- Morocco charges 2,480 in Gen-Z protests over poor governance, health and education

- Kenyan quartet selected to officiate at 2025 Africa Cup of Nations in Morocco

- Morocco's Gen Z protests: What you need to know

- Kenya deepens ties with Morocco, hold first joint cooperation commission

- Morocco: Gen Z protests turn violent, two killed

- Morocco: Police detain dozens in Gen Z protests

This article traces the chronological and political moments behind Nairobi's dramatic turn on the Sahrawi cause—a founding member of the African Union—and how a seemingly quiet 2021 meeting between then-Deputy President William Ruto and Morocco's former envoy to Kenya, Mokhtar Ghambou, helped reshape Kenya's foreign policy trajectory.

1963–1984: Pan-African Roots

Kenya's support for Western Sahara dates back to independence. In 1963, Nairobi joined the UN Special Committee on Decolonisation and endorsed Spanish Sahara's classification as a non-self-governing territory "awaiting the free and genuine expression of the wishes of its people."

This stance was reaffirmed in 1975, when Foreign Minister Dr. Munyua Waiyaki declared at the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) Council of Ministers that "Kenya stands with all Africans still under colonial rule, including the Sahrawi people whose right to choose their destiny is beyond question."

After Spain withdrew from the territory, Morocco annexed the northern two-thirds, and Mauritania took the rest. By 1979, with Mauritania pulling out, Kenya voted for UN Resolution 34/37, rejecting partition and affirming Sahrawi self-determination. Ambassador Joseph Odero-Jowi stated clearly, "Self-determination, not partition, is the only acceptable outcome."

President Daniel Arap Moi played a central mediation role during his tenure as OAU chair. In 1981, at the OAU Summit in Nairobi, Morocco's King Hassan II agreed in principle to a referendum. However, a declassified CIA memo later revealed Rabat's behind-the-scenes efforts to manipulate the process. Moi objected, writing to King Hassan in October 1981: "This action does not contribute to progress... Africa's demand is clear: adherence to OAU decisions and a peaceful settlement for Western Sahara."

In 1984, Kenya voted in favour of SADR's admission to the OAU, prompting Morocco to walk out in protest. "Africa cannot preach decolonisation while denying Western Sahara its seat," said Foreign Minister Elijah Mwangale.

2005–2017: Diplomatic Oscillation

In 2005, President Mwai Kibaki formally recognised SADR and approved ambassadorial exchanges. Morocco retaliated. In 2006, Foreign Minister Raphael Tuju closed SADR's mission in Nairobi, citing "procedural lapses" but denying any shift in Kenya's official position.

Although recognition was held, Kenya refrained from fully operationalising relations. It wasn't until May 2022 that Kenya's envoy, Peter Katana Angore, presented credentials to Sahrawi President Brahim Ghali in exile.

Soon after, Nairobi recalled Angore and revoked his accreditation, a move PS for Foreign Affairs, Korir Sing'oei, justified on strategic grounds. "There is little commercial value in maintaining an envoy to a refugee-based government," he told this outlet.

In 2014, under Foreign Minister Amina Mohamed, the SADR embassy in Nairobi was quietly reopened. "Kenya reaffirms the Sahrawi people's inalienable right to decide their political future," she said.

At the UN General Assembly in 2017, Kenya's UN envoy, Macharia Kamau, echoed that sentiment: "Decolonisation remains unfinished in Western Sahara. The referendum promised in 1991 must proceed."

Other Topics To Read

By then, however, Rabat's influence in African Union politics was growing. Morocco, one of the AU's top financiers, rejoined the organisation in 2017 after decades of absence, launching a subtle but effective campaign against dissenting voices.

One casualty of this campaign was Kenya's Amina Mohamed, who sought to become the AU Commission Chair in 2017. Her candidacy was opposed by Morocco, widely interpreted as retribution for her open support for the Sahrawi cause, including a high-profile visit to Ghali in Algeria's Tindouf region.

Kenya on Monday officially inaugurated its first embassy in Rabat, marking a quiet yet significant shift in its Maghreb diplomacy. (X/Musalia Mudavadi)

Kenya on Monday officially inaugurated its first embassy in Rabat, marking a quiet yet significant shift in its Maghreb diplomacy. (X/Musalia Mudavadi)

2021–2022: Ruto's stand

A year before Kenya's 2022 general election, divisions emerged within the top leadership. President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy—turned-political nemesis, William Ruto, held contrasting views on Western Sahara.

In March 2021, Kenya chaired the AU Peace and Security Council. Then-AU envoy Jean Kamau, now the UN Resident Coordinator in Guyana, cited "military escalation between Morocco and the Sahrawi Republic" as a priority issue. Kenyatta convened a virtual PSC meeting on March 9, calling for "an immediate ceasefire."

Later, Kenya's UN Ambassador Martin Kimani echoed the stance, supporting Resolution 2602 for MINURSO renewal and calling for "an expedited, UN-conducted referendum so the Sahrawi people may exercise self-determination."

Ruto, meanwhile, charted a different course. On March 23, 2021, during a meeting with Ambassador Ghambou in Gigiri, he said: "The autonomy plan under Moroccan sovereignty is the best solution to the Sahara issue." It was a glaring contradiction to official Kenyan policy and, in hindsight, the beginning of a diplomatic pivot.

2022–2023: From tweeting to retraction

Barely a day after being sworn in as President in September 2022, Ruto stunned observers with a tweet announcing Kenya's withdrawal of SADR recognition. The announcement came after an overnight meeting with Moroccan Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita, even as Sahrawi leader Brahim Ghali remained on Kenyan soil for the inauguration.

The tweet was deleted within 11 hours after a domestic and international outcry. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs clarified: "Kenya's long-standing position on Sahrawi self-determination is unchanged. Foreign policy is not conducted on Twitter"—a veiled critique of the incoming Ruto administration by holdovers from the Kenyatta era.

In October 2022, Kenya abstained from voting on UN Resolution 2654 on Western Sahara. Ambassador Kimani diplomatically dissented: "The resolution tilts toward an autonomy outcome without securing the consent of the people concerned. Kenya cannot endorse that."

In September 2023, Ghali returned to Nairobi for the Africa Climate Summit, where he was received with red carpet honours. His presence reignited tensions with Rabat but revealed Kenya's indecision: pivoting diplomatically, yet not entirely severing historical ties.

2024–2025: A quiet, full pivot

Despite Morocco's displeasure, Ghali continued to appear in Kenya's diplomatic orbit. At the 2025 AU Assembly, during the traditional family photo, Ruto stood beside him. At the inauguration of Namibia's first female president, another SADR ally, Ruto sat next to Ghali. "It wasn't a coincidence," an African diplomat told this outlet.

But the real pivot came in May 2025. During the inauguration of Kenya's first diplomatic mission in Rabat, Mudavadi issued a joint statement endorsing Morocco's autonomy plan as "the only credible and serious" solution.

The announcement marked the end of Kenya's historical support for SADR, without any public explanation. Neither Mudavadi nor PS Sing'oei have responded to repeated requests for comment on the shift's rationale or consequences.

A senior Kenyan diplomat who spoke off the record summed it up bluntly: "This is flip-flopping foreign policy. It will provide a case study in international relations classes for years to come."

Top Stories Today