Reexamining the overlooked role of the Asian community in Kenya's development

Lawyers like A.R. Kapila and journalists like Pio Gama Pinto were vocal in articulating the African aspirations

During the recent Makhan Sigh exhibition at the Nairobi Gallery, there was a debate about the claim that the contribution of Asians to Kenya’s independence and socio-economic development is being understated and unappreciated.

The main question at the exhibition was why the writers of Kenya’s independence struggle downplayed the contribution of the Asian community to the independence struggle.

More To Read

- Explainer: All you need to know about the prestigious 'Senior Counsel' title

- Lawyers petition state over killing of advocate Kyalo Mbobu

- Kenya School of Law sets October 31 deadline for training applications

- New Bill could allow president to award 'Senior Counsel' title to politicians, civil servants

- Ethiopian Airlines executive views new Urumqi cargo route as crucial corridor linking Africa-Asia

- Only 26 institutions are licensed to teach law in Kenya, says CLE

The Eastleigh Voice spoke to several people on this matter.

Zaid Rajan, the organiser of the exhibition that showcased heroes from the Asian community such as Pio Gama Pinto and Makhan Singh, argued that the community's contribution has not been well documented and made part of history to be studied.

“I believe the contribution of Makhan Singh and Pio Gama Pinto to Kenya’s independence struggle has not been recorded in equal measures like their native African counterparts,” said Rajan.

To illustrate his point, Rajan questioned why Asians who have contributed positively to political and economic struggles in the country have not been honoured with street names.

“For a street to be named after Pio Gama Pinto, we had to lobby for a very long time. Our quest to have Park Road named after Makhan Singh has however not bore fruits,” says Rajan.

Rajan is the husband of the late Zarina Patel, Singh’s biographer, who was known for dedicating her life to documenting the struggles of the Asian community in independent Kenya.

Former chairman of the Kenya Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board and prominent lawyer Sharad Rao said in an interview recently that many people lack a good understanding of the roles Asians played in Kenya’s independence struggle. Rao told The Eastleigh Voice that despite being few in the country, the community has touched thousands of lives in their humanitarian endeavours and philanthropic deeds.

“Indeed, the Asian community contributed significantly to the independence of the country and its economic emancipation after unchaining itself from the yoke of colonialism,” said Rao.

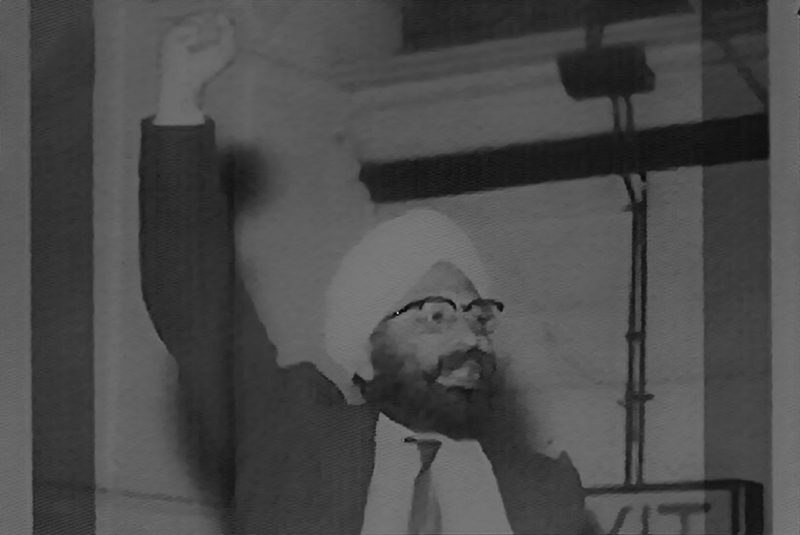

Former chairman of the Kenya Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board and prominent lawyer Sharad Rao. (Photo: Handout)

Former chairman of the Kenya Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board and prominent lawyer Sharad Rao. (Photo: Handout)Former chairman of the Kenya Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board and prominent lawyer Sharad Rao

Rao said that Asian participation in Kenya's struggle for independence during the late colonial period has come mainly through institutions. Political organisations, newspapers, and the trade union movement provided the lines of communication between the Africans, the Asians, and the British colonial government.

In the struggle for independence, many Asians contributed to the African cause. Lawyers such as Friiz de Souza and A.R. Kapila, among others, played key roles in defending Mau Mau suspects and the Kapenguria Six who included Mzee Jomo Kenyatta. Journalists such as Pio Gama Pinto and the trade unionist Makhan Singh were also vocal in articulating African aspirations.

However, after independence, Asians’ political role was severely diminished, partly because the new post-independence government did not encourage this minority community to play a big role in politics.

Furthermore, Mzee Kenyatta’s government introduced an Africanisation policy that barred Asians from applying for civil service jobs and confined their businesses to urban areas (the latter a throwback to the colonial land policy) ostensibly to level the playing field for African participation in the economy. Thousands of Asians with British passports left for the United Kingdom after Kenyatta’s government issued them with “quit notices” and denied them trade licences and work permits.

Those Asians who were left behind, many of whom opted for Kenyan citizenship, began to feel under siege. Their fear that they might also be targeted for expulsion was reinforced in August 1972 when President Idi Amin expelled more than 70,000 Asians from Uganda and when an aborted coup attempt in Kenya, exactly 10 years later, resulted in the looting and destruction of Asian-owned shops by rowdy mobs in Nairobi’s central business district.

Due to the way the colonial state was constructed, some groups enjoyed more privileges than others, a practice that continued even after independence. The state decides who is an “insider” and who is an “outsider”, and which spaces they should occupy. This has led to the politics of exclusion based on tribe or geographical boundaries.

Kenyan Asians also became targets of scapegoating. In the 1980s, politician Martin Shikuku often derided Asians for being mere “paper citizens” who were only interested in exploiting the country economically and whose loyalty and allegiance lay elsewhere.

These statements were echoed by other prominent politicians, such as opposition leader Kenneth Matiba, who in 1996 controversially asked Kenyan Asians to “peacefully pack up and go”, accusing them of racism and of dominating the economy. Since then Asians have largely kept a low political profile, though in recent years many have joined mainstream political parties and even vied for electoral seats, some quite successfully.

The 1960s were a turbulent time for Kenya’s South Asian community. As the decade dawned, the emergency had ended and Kenya was fast moving to independence.

The Asians were apprehensive of their future in Kenya. In 1965, the imposition of exchange controls hit the community hard as many had their savings in British banks, or were educating their children in Britain or the US.

In 1967, the government passed the Immigration Bill requiring all non-citizens to get work permits. British Asians now had to decide whether to take Kenya citizenship or emigrate to Britain.

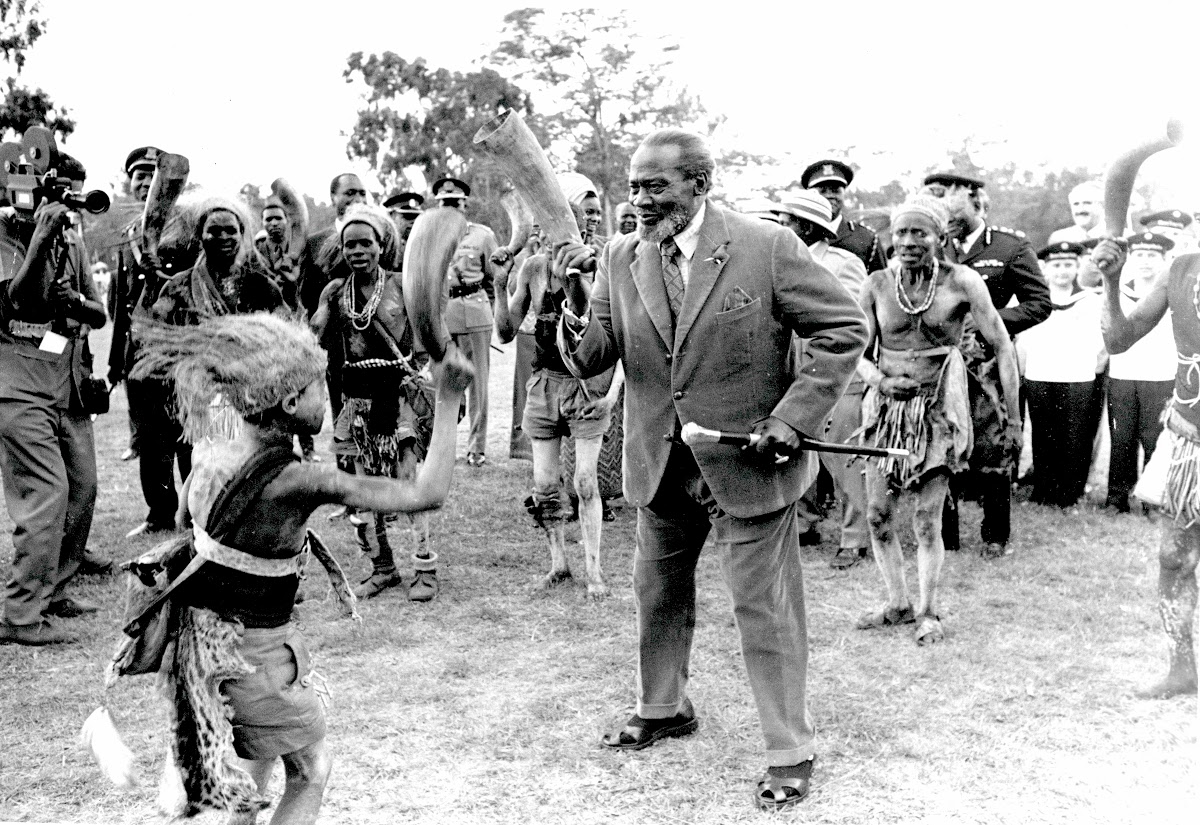

Kenya's first President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta joins traditional dance in a dance. (Photo: Mohamed 'Mo' Amin)

Kenya's first President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta joins traditional dance in a dance. (Photo: Mohamed 'Mo' Amin)

In 2017, the government officially recognised members of the Asian community as a tribe, supposedly as part of an effort to integrate them into mainstream society and to secure their rights in the country’s social and political fabric.

The government said that the move to declare Asians as the East African nation’s 44th indigenous group allowed them to finally become part and parcel of “Kenya’s great family”.

Historian Kenneth Okumu disagrees that the contribution of the community has not been felt. He says that it is the historical happenings that have not been open to their existence in post-independent Kenya.

“For a community that had been categorised in the national census as the ‘other, their acknowledgement was welcomed as long overdue, a progressive gesture that has been pushing the country towards a dream of inclusivity and equality,” says Okumu.

If not properly acknowledged, Okumu warns that the recognition of Asians as a tribe could be seen as an extension of the warped and divisive reality of tribal politics in Kenya.

According to writer Rasna Warah, instead of assigning a tribal identity, Kenyans should be striving “to create a nation where everyone’s rights are respected, regardless of tribe, race, or ethnic group”.

Top Stories Today