Delayed GMO rollout cost Kenya Sh4.1 billion yearly - study

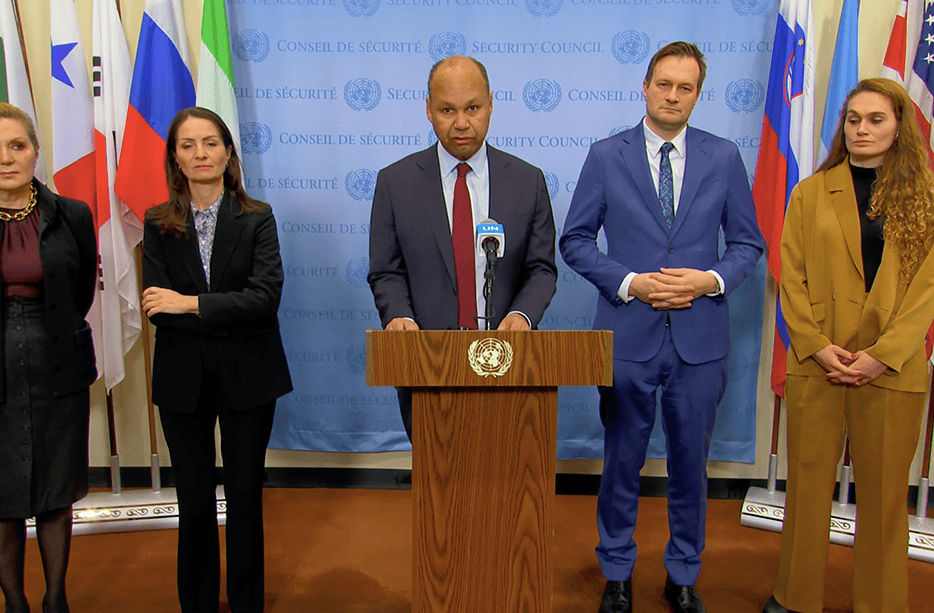

In March this year, the Court of Appeal issued a status quo order that specifically restrained the government from allowing GMO imports or advancing the 2022 cabinet decision.

Kenya technically and institutionally has a functional biotechnology regulatory regime, yet commercialisation of genetically modified (GM) crops has been delayed for years.

This is the reckoning of the experts, who warn that the prolonged delay is costing the country dearly, through lost revenue, missed gains in food security, and stalled efforts to improve farmer livelihoods.

More To Read

- Experts push for food fortification as Kenya’s nutrition crisis deepens

- We decoded the oldest genetic data from an Egyptian, a man buried around 4,500 years ago – what it told us

- Court of Appeal bars importation of GMO foods

- Mutahi Kagwe: Only locally developed GMOs will be allowed in Kenya

- State invites public input on proposed release of GMO maize

- Battle to stop GMO foods in Kenya lands in Court of Appeal

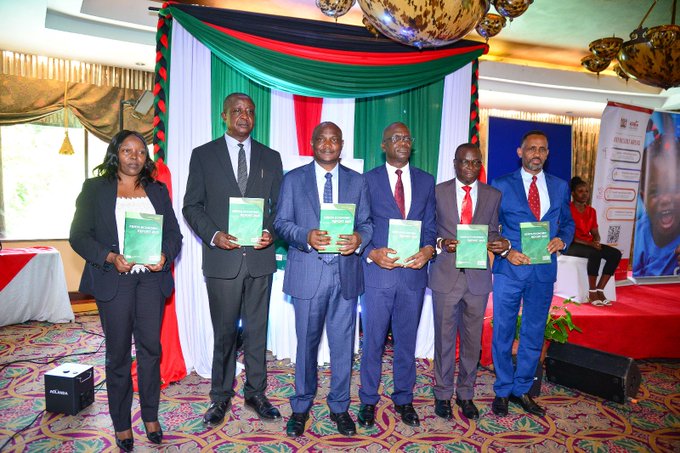

In a joint study led by the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF), they reveal that prolonged regulatory and political delays in the rollout of three genetically modified (GM) crops have cost the country about $157 million (Sh20.3 billion) over the past five years.

This translates to a yearly average of about Sh4.06 billion.

The crops in question are Bt maize, Bt cotton, and the late blight disease-resistant potato.

The history of GM crops in Kenya dates back over 20 years ago when research on Bt cotton started.

It became the first GM crop available to Kenyan farmers in 2020, making the country’s cotton crop less vulnerable to the bollworm pest.

Shortly after, three varieties of Bt maize became ready for commercialisation in 2021, which were said could protect farmers’ crops from maize stem borer and fall armyworm damage, but are still awaiting cabinet approval for commercialisation.

Kenyan scientists are also developing disease-resistant GM varieties of cassava and potato.

Though Bt cotton has been commercialised, the approval and commercialisation processes for both Bt cotton and Bt maize have faced significant delays due to a ten-year ban on the importation of GM crops (2012–2022) and subsequent court cases challenging the lifting of the ban in 2022 by the cabinet.

In March this year, the Court of Appeal issued a status quo order that specifically restrained the government from allowing GMO imports or advancing the 2022 cabinet decision.

The ruling definitively upheld the ban and the original conservatory order issued in November 2022, immediately after the ban was lifted in October.

According to the Foundation, these delays have had notable economic repercussions and have hindered progress in agricultural innovation.

Categorically, the study estimates that five years of delays in adopting Bt maize have cost Kenya's farmers and consumers about $67 million (Sh8.6 billion).

“This loss is largely due to the continued need for expensive pesticides with traditional crops. Had we adopted earlier, farmers could have produced an additional 194,000 tonnes of maize, equivalent to about 25 per cent of Kenya's 2022 maize imports,” the study says.

AATF estimates this forgone production to be 14 times higher than the total maize food aid from the UN World Food Programme (WFP) to Kenya in the year 2023, for instance.

Looking ahead, the Foundation projects that by 2030, the total economic benefits of Bt maize without delay in release could have reached $218 million (Sh28.2 billion).

“The increase in domestic production could also strengthen the country’s crop yields compared to Tanzania, its closest competitor in East Africa.”

Delay in the release of Bt cotton is estimated to have cost farmers and consumers close to $1.2 million (Sh155 million) in the last five years.

“Without the delay, Bt cotton could have been released in Kenya in 2015 rather than 2020 and could have benefited Kenyan farmers and consumers by a total of $ 2.6 million (Sh336.7 million) by 2028.”

Sharing his experience, Joseph Migwi, a farmer from Malindi, says cultivating Bt cotton yields him 1,000kg per acre, earning him around Sh72,000.

In contrast, when he grew conventional cotton, she harvested only 300kg, earning about Sh21,600.

On the other hand, the report estimates that the release and commercialisation of the late blight disease-resistant 3R-gene Shangi potato variety would benefit Kenyan farmers and consumers by $163 million (Sh21.1 billion) and $84 million (Sh10.8 billion), respectively, over a period of 30 years.

“This would significantly strengthen our food security by boosting domestic production of Kenya's second-most important food crop after maize,” the report reads in part.

“A 5-year lag in the release of the 3R-gene Shangi would reduce the benefits to farmers and consumers by $59 million (Sh7.6 billion) and $30 million (Sh3.9 billion), respectively.”

Notably, the battles behind the delayed rollout are a result of the widespread concerns about GMOs, including their potential impact on health, the environment and farmers’ economic independence.

The long-term health effects of GMO consumption, for instance, remain a subject of debate.

Some studies suggest potential links between GMOs and allergic reactions, antibiotic resistance, prevalence in different types of cancer and other health complications, which then means that introducing GMOs into the country’s food system could pose unforeseen risks to public health.

Top Stories Today