Why anchoring Dishi na County in law could transform Nairobi’s children’s futures

Nairobi’s Dishi na County school feeding programme now serves over 300,000 children. Experts warn it must be anchored in law to survive political shifts and protect vulnerable learners’ nutrition.

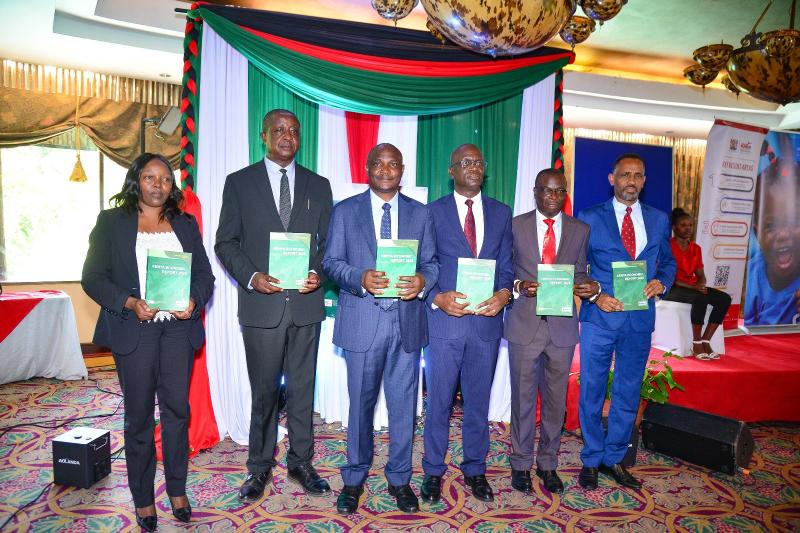

According to the 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS), conducted in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, much remains unaccomplished in tackling the triple burden of malnutrition—undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and rising obesity. The report shows that children from the poorest households are far more likely to be stunted than those from wealthier families.

To minimise the impact, the Ministry of Health has rolled out a range of policies under the Kenya Nutrition Action Plan (2018–2022), Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) guidelines, the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding (which reached 60 per cent in 2022), nutrition-sensitive cash transfers, and school feeding programmes. However, experts warn that unless these initiatives are anchored in law, the gains may remain fragile and easily reversed by political changes or budget cuts.

More To Read

- 10 counties in critical need of urgent food, water as government seeks Sh13 billion to avert hunger

- Kamukunji MP Yusuf Hassan launches free skills courses as over 600 youth turn up to register

- Maternal and newborn health in crisis as millions born in conflict zones, Save the Children warns

- South Sudan health system on brink as conflict and cholera spread, MSF warns

- Parents lead the fight against malnutrition as Turkana’s ACCEPT project shows big results

- MSF raises alarm over extreme malnutrition as Sudan crisis deepens

A mother’s struggle in Huruma

In Nairobi’s Huruma informal settlement, where poverty and food insecurity are daily realities due to ongoing economic hardship, these statistics translate into lived suffering. Abigael Mulwa, a mother of three, hawks fruit to feed her family. She often manages only one meal a day, and rarely a balanced one. Before Dishi na County, her eldest daughter frequently missed school because of hunger.

“Now that schools have closed, they keep asking me, ‘Mum, when are we going back to school so that we can eat?’” she says.

At home, her children usually get one meal a day, two on a lucky day. This has been the situation even during her pregnancies. To the naked eye, it is clear that the children lack essential nutrients. Abigael acknowledges this, but says that given her economic circumstances, there is only so much she can do.

For the past two years, her two eldest daughters have benefited from the programme, bringing her a sense of real relief.

“I only have to think of what they will eat when they come home in the evening.”

For her, the programme is more than just food; it is a lifeline. It keeps her daughters in school, provides them with essential nutrients, and gives them a real chance to grow cognitively strong enough to compete socially and economically.

“I can’t wait for the younger one to join school too. That way, when I go hawking, I can go as far as I can, knowing we will meet later in the evening and they won’t be as hungry.”

Nutrition and brain development

Nutritionist Pamella Nyongesa stresses that brain development begins even before birth.

“The process starts when a woman discovers she is pregnant,” she explains.

Yet women in informal settlements often lack adequate nutrition during pregnancy, setting children back from the very start.

Proper nutrition in early childhood is a fundamental foundation of lifelong health. Chronically hungry children suffer from weakened immunity, reduced cognitive function and poor educational performance.

Other Topics To Read

Globally, UNICEF reports that at least one in three children under five is not growing well due to stunting, wasting or being overweight, while one in two suffers hidden hunger caused by micronutrient deficiencies.

Only one in five children aged six to 23 months in the poorest households receives the minimum recommended diverse diet for healthy growth and brain development.

Without intervention, these children face diminished mental capacity, limiting their ability to thrive in school and beyond.

Why county programmes matter—and why law matters even more

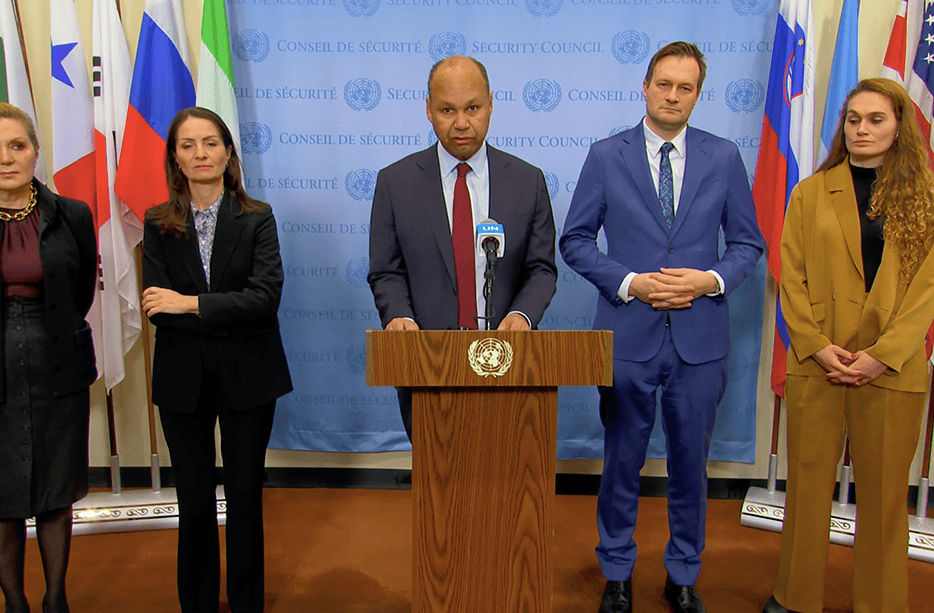

The Dishi na County initiative demonstrates how targeted interventions can help break this cycle. It feeds more than 300,000 children across Nairobi through centralised cooking and Near Field Communication technology that tracks real-time data.

The meals are rich in essential nutrients. Beyond improving nutrition, the programme boosts school attendance and retention, giving marginalised children a fair chance at education.

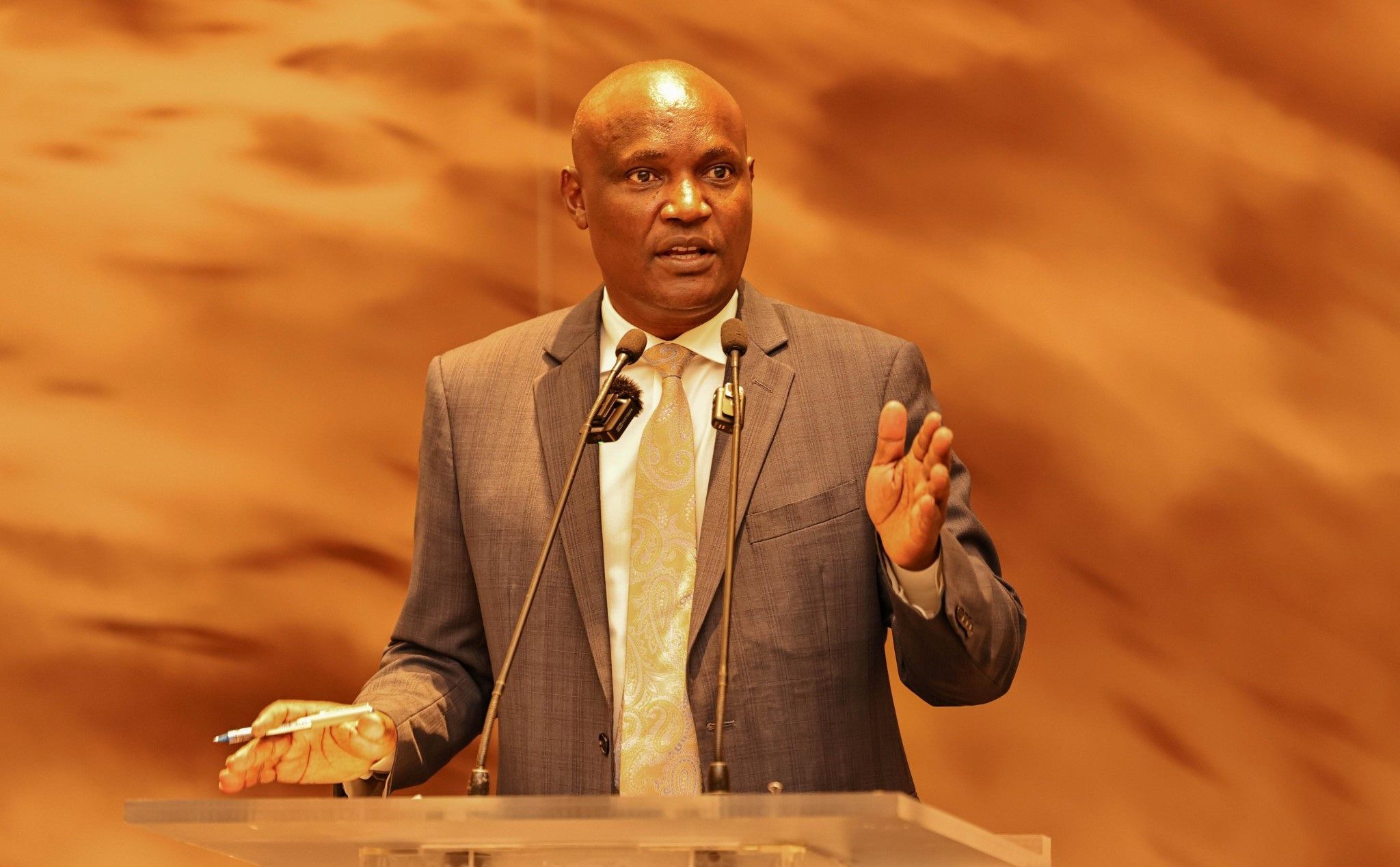

Pamella argues that anchoring such programmes in law is critical. Informal settlements make up nearly 60 per cent of Nairobi’s population, yet children living there are often excluded from consistent support.

By embedding feeding programmes into county policy—and ideally into national law—governments can guarantee sustainability, protect initiatives from political shifts, and expand their reach, perhaps by adding a morning snack or an afternoon meal to further support learning and brain development.

Drought makes legal protection urgent

The October to December short rains have underperformed, exposing an estimated 2.1 million people across 32 counties to food and nutritional insecurity. The Kenya Meteorological Department predicts that these counties will require food, nutrition and health interventions for both humans and livestock over the next six months, until the March to May long rains harvest is ready.

Pamella insists the time for action is now. “Nutrition is not just about providing food for children. It is about building brains, shaping futures, and breaking cycles of poverty.”

For mothers like Abigael, the availability of Dishi na County offers hope that their daughters will not only stay in school, but also grow into healthy, capable adults.

Top Stories Today