Rotavirus: The silent danger threatening toddlers and why early vaccination is key

While handwashing, proper sanitation, and breastfeeding can help reduce the risk of infection, experts agree that vaccination offers the most effective protection.

For parents of young children, few things are more heartbreaking than watching their toddler lie down, feverish and unable to keep down even a sip of water.

As a mom or dad, you feel helpless, pacing between the bed and the phone, hoping they will feel better, yet terrified they will not. This is exactly what rotavirus can do, and shockingly, nearly every child will face it before their fifth birthday, as health experts say.

More To Read

- Your washing machine is not self-cleaning: Here’s how to keep it fresh and odour free

- New study links smartphone use on the toilet to rising haemorrhoid cases

- Why camel milk is gaining ground and why experts urge safer consumption

- Clean hands, safe bites: Why everyday food habits matter more than you think

- Cost of neglect: How poor sanitation is fueling cholera risk in informal settlements

- South Sudan launches lifesaving vaccines to fight pneumonia, diarrhoea in children

Rotavirus is not just a bad stomach bug that you think may cause small diarrhoea that goes away. It strikes fast and hard, often causing severe diarrhoea, vomiting, high fever and dehydration, all in tiny bodies that have very little reserve.

“It felt like it came out of nowhere,” one parent told The Eastleigh Voice.

“One day she was laughing and playing, and the next, we were rushing to the ER because she couldn’t even lift her head.”

For Miriam, she got a phone call from her nanny that her child had been vomiting since morning, after just taking a cup of uji.

“My nanny told me she could not keep anything down, even water. In the evening, when I was coming from work, I noticed she just wanted to lie down; she looked so weak and only wanted to be held,” Miriam recounts.

The good news is that it is preventable, and a safe and effective vaccine exists, which is part of the recommended routine immunisations for infants.

But timing is everything; the first dose needs to be given as early as six weeks old, and the next dose is given at 6 months. The third dose may be administered depending on the brand of vaccine.

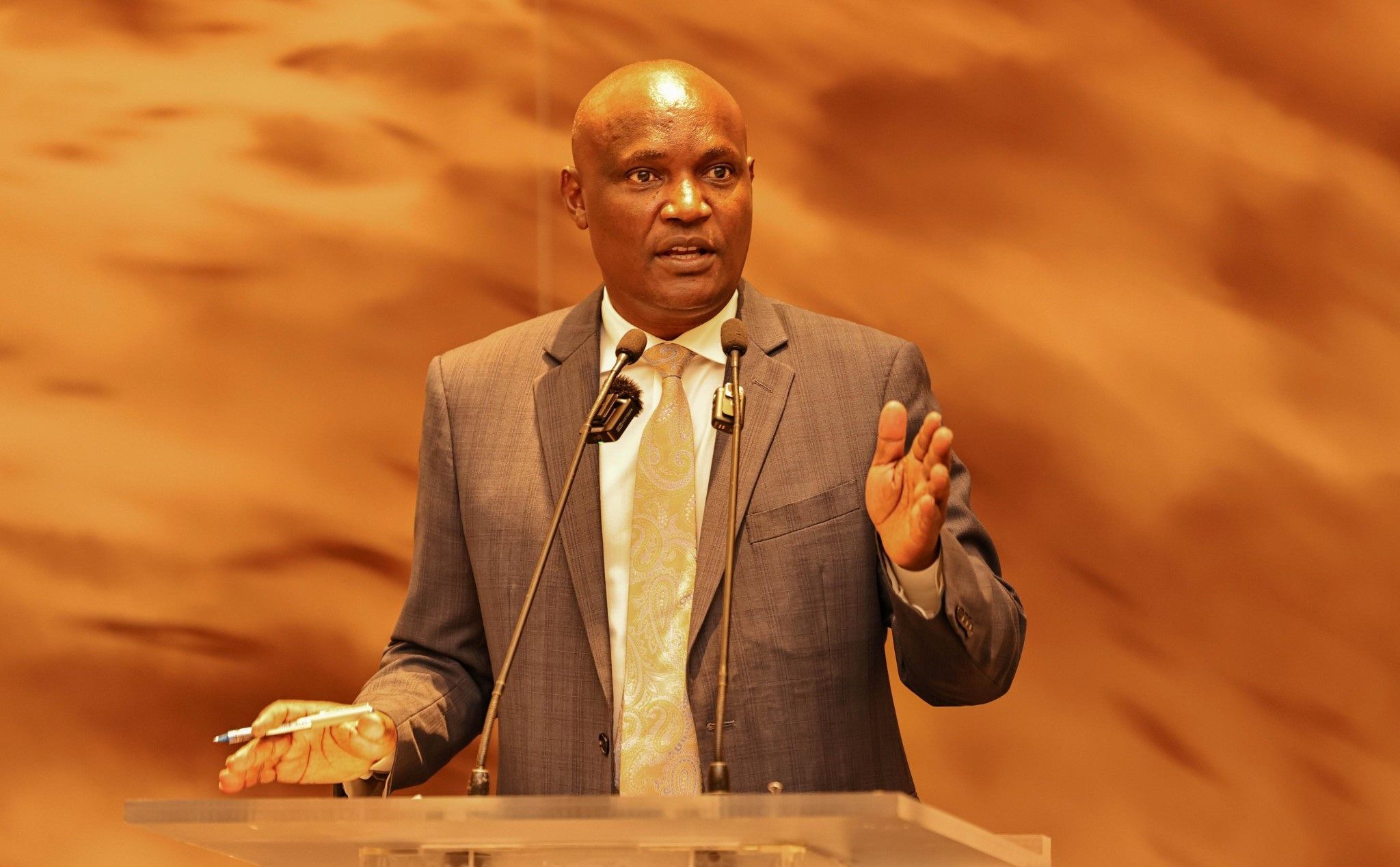

“Rotavirus is a highly contagious virus that causes severe diarrhoea and vomiting in young children. It spreads through unwashed hands, contaminated surfaces, and even shared toys,” explains Dr Jacinta Wangari, a Nairobi-based paediatric consultant.

“This virus is often mistaken for a regular stomach bug, but it is far more aggressive and far more dangerous, especially for infants and toddlers. What makes it so serious isn't just the vomiting and diarrhoea, but how quickly it leads to dehydration in such small bodies.”

Wangari explains that inside your child’s stomach, the rotavirus attacks the lining of the small intestines, the very place where nutrients and fluids are absorbed.

As the virus multiplies, it damages these delicate cells, leading to inflammation, cramping, and a sharp or twisting stomach pain that even toddlers will try to describe with tears or by curling up in discomfort.

Their belly may feel bloated, tender to the touch, or rumble with constant gas and movement.

This is not just a bad day; it is a medical emergency waiting to happen if not treated quickly. And it happens fast, because the intestines can’t absorb fluids properly, even mild vomiting or diarrhoea can lead to rapid dehydration, which is why doctors urge parents to watch for warning signs like dry lips, sunken eyes, no tears when crying, or fewer wet diapers.

“The disease usually starts with a sudden fever, followed by vomiting and watery diarrhoea. For some children, especially those under two years old, this can escalate quickly into severe dehydration, which may require hospitalisation,” says Wangari.

Why are toddlers especially susceptible?

Toddlers are natural explorers; they crawl, touch everything and put their hands in their mouths constantly. That is part of normal development, but it also puts them at risk.

“Children at that age have not yet built strong immunity, and if they haven’t been vaccinated, they are even more vulnerable. And since it’s a viral infection, antibiotics won’t help as much, but doctors may give the dose if they suspect a secondary bacterial infection,” she adds.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), rotavirus is the leading cause of acute diarrhoea in children globally, responsible for hospitalising hundreds of thousands of children every year, especially in low-resource areas.

In Kenya, paediatric units report spikes in rotavirus-related cases during the cold seasons, further straining healthcare systems.

"The ORS (oral rehydration solution) is the most important part of treating rotavirus because it prevents and treats dehydration, which is the main danger of the illness; it helps replace lost fluids and electrolytes, supports recovery, and can save lives."

The virus can remain in a child’s body and continue to be shed in the stool for 10 days or even longer, even after symptoms improve.

Wangari notes that during this time, the child can still infect others, especially through unwashed hands or contaminated surfaces; that is why good hygiene and handwashing are also very important to prevent the spread to family members or other children.

The hidden costs

Aside from the obvious toll on a child’s health, the virus carries heavy economic and emotional costs for families.

“Parents are forced to take time off work, some pay out-of-pocket for hospital stays and medication, and the emotional stress of watching your child suffer is immense,” Wangari notes.

On average, hospital stays linked to rotavirus last about three days, and many cases require follow-up visits to check if it has fully cleared.

Vaccination: the best defence

While handwashing, proper sanitation, and breastfeeding can help reduce the risk of infection, experts agree that vaccination offers the most effective protection.

“The rotavirus vaccine stimulates the baby’s immune system to fight off the virus before it causes serious illness. It’s given orally in two or three doses, depending on the brand, and should ideally be completed before a child is six months old,” says Wangari.

In Kenya, the rotavirus vaccine is available free of charge under the Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI), although some hospitals may charge for the routine.

“Talk to your paediatrician or go to your local health facility, the earlier the vaccination is completed, the better the child’s chances of avoiding a severe infection,” she advises.

Know the warning signs

Rotavirus is a common illness, but with the right care, it does not have to be dangerous.

"With timely vaccination, good hygiene practices, and quick action when symptoms appear, parents can protect their toddlers from the worst effects of this stubborn virus," says Wangari.

Parents should watch out for signs of dehydration, such as dry mouth, sunken eyes, lack of tears when crying, decreased urination, or lethargy (feeling of vomiting).

"If your child has diarrhoea and is not keeping fluids down, do not wait. Get medical help immediately," warns Wangari.

Symptoms of rotavirus typically last between 2 to 8 days, and in some cases, children may also exhibit respiratory symptoms like coughing or neurological signs such as irritability or drowsiness. However, it does not affect the lungs directly since it affects the gut, but the child can have both a viral infection affecting the respiratory system and have the rotavirus affecting the gut, since they are both common during the cold season.

Although symptoms may subside, the virus can remain in the body for up to 10 days or longer, shedding in faeces and making the child contagious.

"A child may appear better but can still be spreading the virus," Wangari notes.

Diagnosis is usually confirmed with a stool test, and blood tests may show normal white blood cell levels, which is typical of viral infections, but she or he may still be sick.

Treatment for rotavirus is mainly supportive, focusing on maintaining hydration through fluids and electrolytes, as there is no specific antiviral treatment.

"The best protection remains prevention through vaccination and rehydration through ORS if sick," Wangari emphasises.

Top Stories Today