Mist and metal: Coltan grab in eastern DR Congo

According to United Nations estimates, Rubaya alone accounts for more than 15 per cent of the world's tantalum supply.

In the mist-veiled highlands of Masisi territory, a silent war for control over one of the world's most strategic minerals is raging. Rubaya, a remote town in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), has once again found itself at the heart of a global supply chain entangled in armed conflict and rebel rule.

Since April 2024, the March 23 Movement (M23) rebel group has maintained control over Rubaya's lucrative coltan mining sites. The ore, columbite-tantalite, commonly known as coltan, yields tantalum, a rare metal essential for manufacturing smartphones, fighter jets, medical implants, and advanced electronics. According to United Nations estimates, Rubaya alone accounts for more than 15 per cent of the world's tantalum supply.

More To Read

- M23 rebels capture eastern DR Congo city of Uvira as thousands flee to Burundi

- UN warns human rights face growing threats worldwide in 2025 as funding for activists falls

- UN hails DR Congo-Rwanda peace deal amid ongoing hostilities in the east

- Scepticism grows over DR Congo-Rwanda peace deal

- African leaders hail historic peace agreement between Rwanda and DRC

- DR Congo, Rwanda leaders to sign peace deal in US

Clinging to the steep slopes of Masisi's fractured hills, the Rubaya mine spills downward like a staircase carved into weathered soil.

Sitting at an altitude of about 2,000 meters, Rubaya is not only a vertical economy but also a test of physical endurance. During a recent field visit, granted after weeks of negotiations with M23 rebels, Xinhua reporters had to lean on tree branches fashioned into walking sticks, guided step by step by local miners.

Each stride up the crumbling ore mounds left one gasping for air, as thin oxygen and unstable footing drained strength. In contrast, Congolese miners, long accustomed to the terrain, moved with effortless agility, like antelopes scaling the hillside.

Across the slopes, narrow mine shafts plunge into the earth – dark, vertical tunnels that vanish into silence, save for the sounds of breath and beating hearts. Inside, teams of 60 to 70 miners descend daily, navigating each claustrophobic shaft with headlamps and pickaxes. They chip away at the ore by hand, passing the minerals upward in an improvised relay system. The deeper the descent, the heavier the air. To prevent suffocation, oxygen pumps hum steadily at the entrances, serving as lifelines for those toiling for minerals down below.

Higher up, the ridgelines are buzzing with activity. The mountaintop hosts a bazaar where traders peddle water sachets, fresh local pastries, flashlights, and boots. Women balance crates on their heads. Boys shout as they drag sacks of gravel. The slopes tremble with movement, a human anthill driven by a hierarchy called the yearning for life.

Overlooking it all are M23 fighters, stationed in scattered outposts or patrolling the trails. They monitor operations, occasionally stopping workers to check permits or update registries.

An M23 official said around 10,000 miners are now "registered", although the actual number, given the vast hillside and transient labour force, could be much higher.

"On good days, we can dig up to 70 kg of minerals. Choosing where to dig and building a shaft is a bit of a gamble. But in Rubaya, with years of experience, it's hard to lose," said one supervisor.

Throughout the escorted visit, Xinhua reporters were allowed to use cameras, but interviews were closely monitored.

M23 officials said pregnant women and minors are banned from working in the mines, but teenage boys and women were visibly present on the slope.

"Guns are not allowed inside the mining zone. That's part of the manifesto of reforms under the M23 administration," said an M23 officer.

According to one trader who asked not to be named, almost every child in Rubaya spends half their life working in this mine. "The minerals here are not even buried deep like in other places," said the trader, who earns a minimum of 47 U.S. dollars per bag of minerals on the local market.

Contaminated supply chains

The M23 takeover has turned Rubaya into the epicentre of what UN reports describe as "the largest contamination of mineral supply chains in the Great Lakes region in a decade."

Under the M23, Rubaya's miners have been offered higher wages than under state oversight, part of what observers see as a dual strategy of incentives and coercion.

Before the M23 seized Rubaya, artisanal miners earned less than 3 dollars a day. Now, as the rebel group encourages them to stay, their salaries have at least doubled, many miners told Xinhua.

"I get paid daily, and our wage depends on how much we extract. Honestly, we've been paid better since they (M23) took over," said a miner interviewed on site. He also requested anonymity.

According to multiple UN Groups of Experts' reports released in 2024, the M23 has created a de facto "mining ministry" that controls all local output, restricts trade to approved buyers, and monopolises export routes as the ore moves through neighbouring countries to the global market.

The rebels have imposed taxes on minerals extracted from the region, such as 7 dollars per kg of coltan and 4 dollars per kg of tin, generating estimated revenues of over 800,000 dollars per month from the trade and transport of 120 tonnes of coltan in Rubaya, according to UN reports.

"The actual number should be much higher," said a villager who requested anonymity.

UN reports noted that in addition to financial extortion, civilians are being subjected to forced labour, with many compelled to build roads and transport ore under duress.

Local communities were also coerced into "salongo," a term once used to describe voluntary community labour but now repurposed to mean unpaid, mandatory work for the repair and maintenance of roads essential for ore transport.

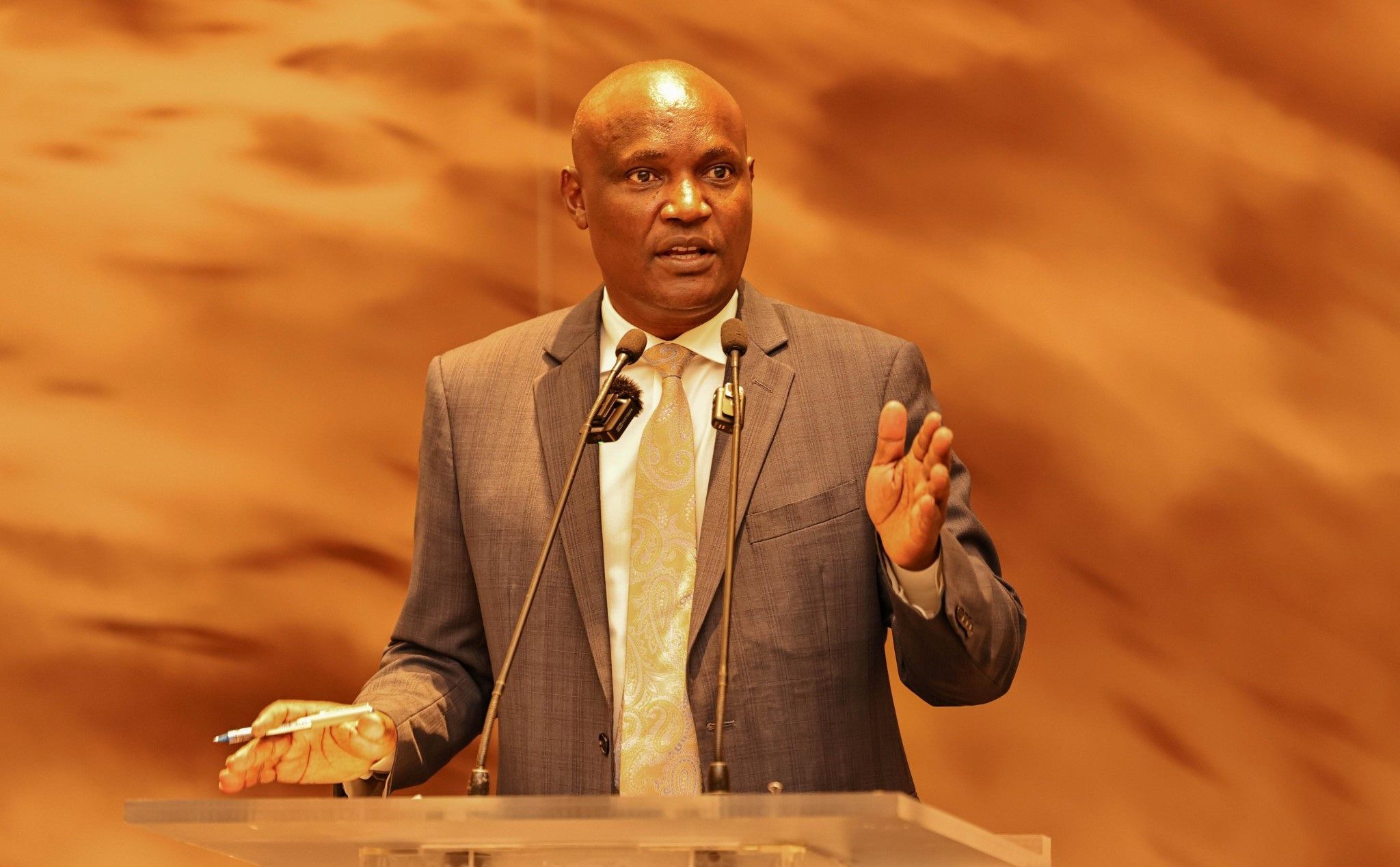

During a formal briefing for the UN Security Council in 2024, Bintou Keita, a special representative of the UN Secretary-General in the DRC, said the revenue stream was fuelling the strength of the rebel group, enabling it to sustain military operations while exploiting civilians and undermining peace efforts in the region.

Keita also expressed concern that the M23 has established a "parallel administration" in Rubaya, appointing positions such as governors and mining officials and managing the extraction and sale of minerals through de facto rebel ministries.

"This undermines state authority and erodes national sovereignty in the eastern DRC," she said.

Top Stories Today