Rwanda, DRC sign Washington Peace Accord amid visible hostility

Rwanda’s Paul Kagame and DRC’s Félix Tshisekedi signed a US-brokered peace deal in Washington while barely acknowledging each other, underscoring unresolved tensions and the mineral-fuelled conflicts still destabilising eastern Congo.

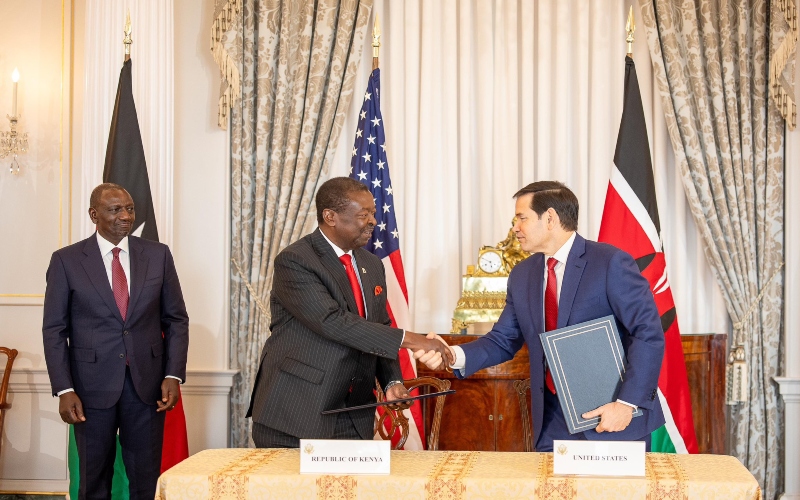

What unfolded in Washington was not merely a diplomatic ceremony but a study in cold peace: an accord signed by two presidents who could barely acknowledge each other across the table.

The leaders of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Paul Kagame and Félix Tshisekedi, arrived to ink a US-brokered peace agreement, yet spent the entire event refusing eye contact, exchanging no words and projecting the unmistakable hostility that has defined their decade-long standoff.

More To Read

- Explainer: Why DR Congo-Rwanda peace deal faces tough reality

- US sanctions armed group, companies profiting from illegal mining in DRC

- Rwanda Parliament dismisses 'unfounded allegations' by Congo house speaker

- President Kagame casts doubt on US-brokered peace deal with DR Congo

- IOM welcomes Rwanda–DRC peace deal, urges tangible impact for displaced communities

The choreography itself betrayed the tension. When Tshisekedi finished signing his copy, he could not bring himself to pass it to Kagame.

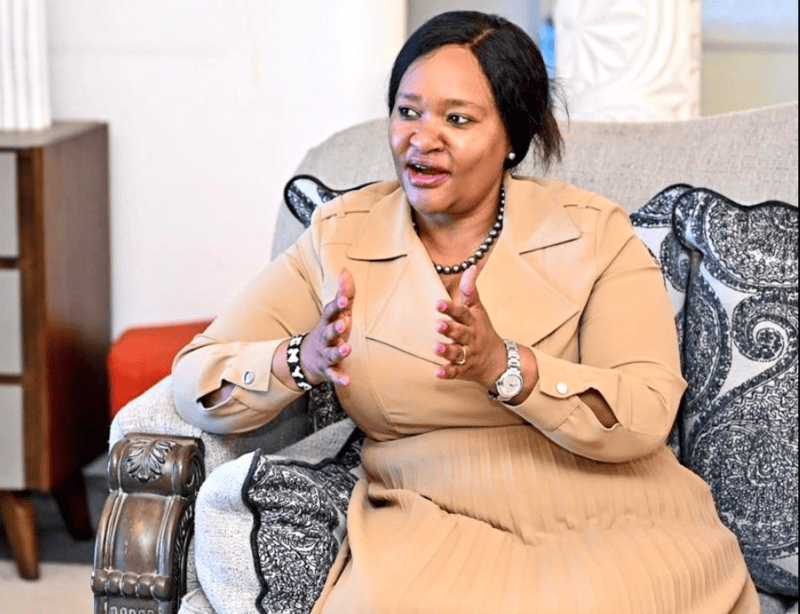

The task fell to the US Chief of Protocol, Monica Crowley, who shuttled documents between the two men like a mediator in a high-stakes divorce. Kagame reciprocated the snub moments later.

Their speeches did little to soften the frost. Kagame, who spoke first, framed the dispute as a 30-year failure of African mediation, lauding President Donald Trump for introducing "a new and effective dynamism... even-handed, never taking sides."

He added - with an unmistakable edge - that "Rwanda will not be found wanting".

Tshisekedi ignored Kagame entirely. Instead, he congratulated Angola's João Lourenço and Kenya's former president Uhuru Kenyatta for earlier mediation efforts, pointedly erasing Rwanda's leader from the diplomatic picture.

Trump, for his part, oscillated between jest and geopolitical theatre. Mispronouncing both leaders' names, he quipped that Kagame and Tshisekedi had "spent a lot of time killing each other" and would now "spend a lot of time hugging... and taking advantage of the United States economically".

Kagame laughed; Tshisekedi did not.

Washington's intervention was, in geopolitical terms, a forced modus vivendi, the kind of externally imposed settlement familiar across Africa when regional mechanisms falter, and the principals cannot stand each other.

This was not without precedent. When Sudan and South Sudan signed the 2012 Addis Ababa agreement, Omar al-Bashir and Salva Kiir refused to interact and fled the room moments after signing.

When Ethiopia and Eritrea concluded the Algiers Agreement in 2000, Meles Zenawi and Isaias Afwerki avoided each other entirely.

The African Union Commission (AUC) nonetheless hailed the Washington deal as a "significant milestone" for the Great Lakes Region.

Yet the structural drivers remain unaddressed.

Since 1998, eastern Congo has been consumed by a revolving cast of rebel groups, militias, foreign backers and a fatigued UN peacekeeping mission.

Other Topics To Read

At the centre of it all lies the paradox of plenty: the DRC's extraordinary mineral wealth - cobalt, coltan, copper and gold - which should have financed development but instead financed war.

Top Stories Today