From wheelchair to walking: The miracle of dialysis that fuels a nurse’s passion in Eastleigh

As a nephrology nurse, commonly known as a dialysis nurse, Kalima specialises in treating patients with chronic kidney disease and kidney failure.

Watching patients arrive in wheelchairs—some barely conscious, others clinging to life—and later walk out unaided after just four hours of dialysis is what fuels Julius Kalima’s passion for nephrology.

It is a powerful, transformative moment he witnesses regularly at Health Gate Hospital in Eastleigh, where he serves as a renal nurse. For Kalima, these are not just medical successes—they are deeply personal triumphs.

More To Read

- Residents of Eastleigh’s Seventh Street demand urgent road repairs

- KNH clarifies failed kidney transplant amid patient’s police report

- Study finds patients quickly regain weight after coming off Ozempic

- Court hears how police surveillance systems tracked suspects in Ahmed Rashid murder case

- Residents demand action as borehole drilling company renders Yusuf Haji Avenue impassable

- Safaricom’s Ndoto Zetu initiative elevates maternal health in Kamukunji's Eastleigh with bed donation

“It’s incredible. A patient comes in unable to move or speak, and after one dialysis session, they’re up, alert, and even walking. That’s why I do this work,” says Kalima.

As a nephrology nurse, commonly known as a dialysis nurse, Kalima specialises in treating patients with chronic kidney disease and kidney failure. These are individuals whose kidneys can no longer perform essential functions, such as removing waste, excess fluid, or toxins from the body. For them, dialysis is not merely a treatment option—it is a lifeline.

As the number of people diagnosed with chronic kidney disease continues to rise across the country, Kalima is increasingly concerned about the root causes, particularly the late detection of hypertension and diabetes. These ‘silent killers’ often go unnoticed until irreversible damage has already been done to the kidneys.

“There’s a huge delay in diagnosis. If more people had regular check-ups and managed conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes early, we could prevent many cases of kidney failure.”

Kalima advocates for greater awareness, regular health screenings, and consistent adherence to medication. He believes that proactive care can help many individuals avoid the need for dialysis altogether. “If someone keeps their blood pressure under control, they may never have to step into a dialysis unit.”

He was drawn to renal nursing because of the immediacy of its impact. “In nephrology, you see the results of your care almost instantly.”

That sense of urgency and reward has shaped his approach to nursing and keeps him going, even during the most demanding shifts.

He manages up to eight patients per session, with each dialysis treatment lasting around four hours. The work demands both emotional resilience and technical precision.

Dialysis machines must be closely monitored, and even minor patient movements can trigger alarms that require immediate intervention.

“For some people, this job is exhausting. But for me, knowing that showing up today means someone gets to live to see tomorrow—that’s all the motivation I need,” Kalima admits.

He recalls a particular night when he was called in at 2 am to attend to a patient in a coma who needed urgent dialysis. “After treatment, they woke up. A few days later, they were walking. That moment still stays with me—it reminded me why this work matters.”

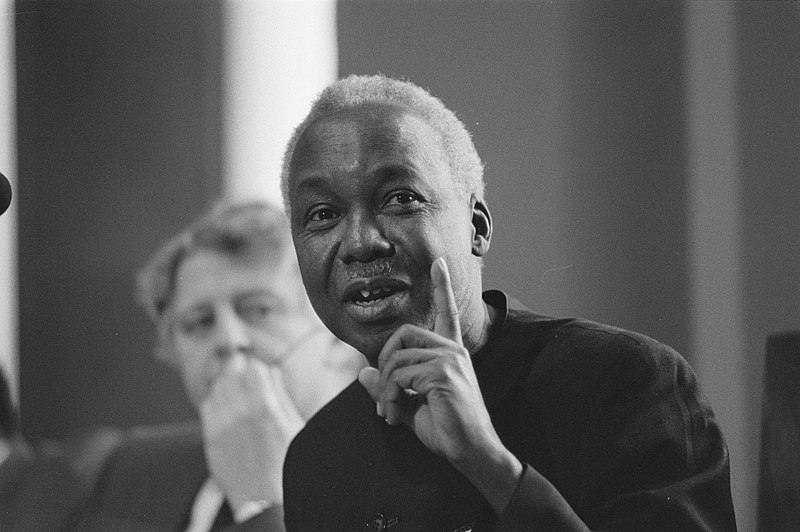

Julius Kalima, a nurse at Health Gate Hospital in Eastleigh, prepares equipment ahead of patient admission on May 12, 2025. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Julius Kalima, a nurse at Health Gate Hospital in Eastleigh, prepares equipment ahead of patient admission on May 12, 2025. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Kidney failure

In its advanced stages, kidney failure affects nearly every system in the body. Without functioning kidneys, harmful substances like urea and creatinine build up in the blood, leading to severe fluid retention and swelling, breathing difficulties caused by fluid in the lungs, fatigue, nausea, loss of appetite and anaemia due to decreased red blood cell production.

“Most people don’t realise they have kidney problems until it’s too late. By the time symptoms appear, both kidneys are often already compromised,” he says.

This reality reinforces his commitment to creating awareness and early intervention, key pillars in reducing the long-term burden of kidney disease in Kenya and beyond.

In addition to providing direct patient care, Kalima is also responsible for operating and maintaining the dialysis machines—a task that demands accuracy and constant vigilance.

“I see every treatment as a chance to give someone one more day,” he says. “And sometimes, that one extra day means everything.”

Kalima takes a moment not only to reflect on the joy and fulfilment his work brings but also to encourage his fellow nurses.

“Nursing is a calling that requires so much of us,” he says. “But in giving to others, we must not forget ourselves. I urge my colleagues to prioritise their well-being too—to make time for rest, renewal, and self-care.”

For Kalima, renal nursing is far more than a profession—it is a purpose. In the steady rhythm of dialysis machines and the small victories of patient recovery, he finds meaning, hope, and the drive to carry on. His work is a quiet but powerful reminder that compassion, commitment, and clinical excellence can restore life—one patient, one session at a time.

In Kenya, the Kenya Renal Association estimates that over 4 million people are currently living with kidney disease, a number projected to rise to 4.8 million by 2030. This alarming trend highlights the urgent need for more trained nephrology and renal nurses to meet the growing demand for kidney care services, including dialysis.

Kidney dialysis is not only life-sustaining for patients—it is also highly demanding on nurses. Each dialysis session can last up to four hours, during which nurses must closely monitor the patient’s vital signs, operate complex dialysis machines, and respond swiftly to any complications.

Managing multiple patients per shift, often with varying degrees of illness, adds to the physical and emotional intensity of the role.

Renal nurses must also ensure infection control, manage fluid balance, and support patients who are often coping with anxiety, chronic fatigue, or end-stage disease. The job requires not just clinical expertise, but empathy, stamina, and constant attentiveness.

As the chronic kidney disease patient population grows, the pressure on these nurses is mounting—making it critical to invest in training, staffing, and support systems to prevent burnout and maintain high-quality care.

Top Stories Today