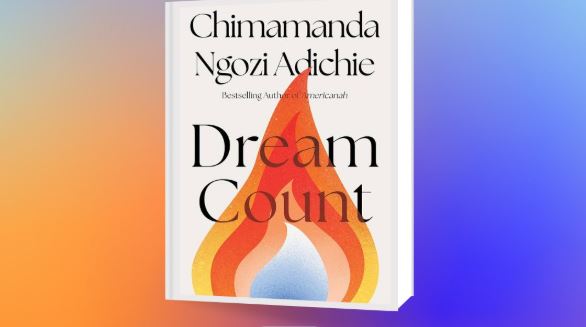

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s new book Dream Count explores love in all its complicated messiness

Dream Count also broadens Adichie’s artistic range – for example, the novel features drug-taking scenes in Abuja, which constitute largely uncharted territory in the author’s work.

By Daria Tunca

Award-winning Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s new novel Dream Count has landed. It’s been over a decade since Adichie published her previous novel, Americanah, following on global successes of Half of a Yellow Sun and Purple Hibiscus.

Adichie’s work is widely studied by academics, not least African literature scholar Daria Tunca. She told us what Dream Count is about and whether it’s worth reading.

***

What’s the story about?

Dream Count tells the intersecting stories of four African women. The novel recounts the characters’ hopes, dreams and struggles, interweaving flashbacks from their childhood and earlier adulthood with episodes set in the narrative present, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The first woman is Chiamaka, a US-based travel writer from a wealthy Nigerian family. She spends much of her adult life looking for the ideal romantic partner.

Chiamaka’s narrative is followed by the story of her friend Zikora, a Nigerian lawyer who also lives in the US. She gives birth to a baby boy after her boyfriend has left her.

The third section is devoted to Kadiatou, Chiamaka’s Guinean housekeeper. Kadiatou is sexually assaulted by a powerful guest in the hotel where she works as a cleaner – a story inspired by the real-life case of Nafissatou Diallo and Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

The book ends with the story of Chiamaka’s cousin Omelogor, a banker in Nigeria’s capital city, Abuja. In addition to her banking job, Omelogor maintains a website giving life advice to men, and she spends a short time in a US university researching pornography.

The novel presents an engaging, occasionally humorous, and deeply moving portrait of these women as they negotiate social expectations, especially when it comes to marriage and motherhood.

How does it add to Adichie’s literary output?

Adichie’s fiction has always given pride of place to the experiences of Nigerian women.

Some of her most memorable characters have included the teenage Kambili in Purple Hibiscus (2003), who is caught between conservative and progressive views of Catholicism. Another is the blogger Ifemelu in Americanah (2013), who spends years in the US without ever forgetting her first love, Obinze, whom she left behind in Nigeria.

Dream Count tackles some aspects of the female experience far more explicitly than Adichie’s previous work. For example, the book discusses physical issues related to women’s bodies (from fibroids to the pain of childbirth). It extensively explores misogyny, which is perpetuated in different forms by both men and women.

Above all, Dream Count is about human connections. Much of the novel depicts romantic relationships, friendships between women, and mother-daughter interactions.

Despite life’s challenges, the novel suggests, our loved ones are sometimes more attuned to our emotions than we might be ourselves.

Dream Count also broadens Adichie’s artistic range – for example, the novel features drug-taking scenes in Abuja, which constitute largely uncharted territory in the author’s work.

Was it worth the 12-year wait?

Emphatically, yes.

Dream Count rewards the attentive reader who is willing to let the book slowly add layers of nuance. The novel recounts the women’s lives one by one, revisits narrative episodes from different perspectives, and gradually pieces together the puzzle of the characters’ emotional journeys.

While Dream Count features Adichie’s trademark humour and biting satire, it mostly stands out for its unfiltered portrayal of women who are in turn passionate, vulnerable, infuriating, resilient, and dignified.

There’s a growing body of African work about love and relationships. Why is this important?

Quite simply, it is important because love matters; well-crafted love stories help us grow.

In the African literary context, books like this are all the more important as they show that, in the past few years, African writers have assertively pushed back against the “single story” – the stereotypical portrayal of the continent as plagued by poverty and violence – that Adichie so eloquently condemned in her 2009 TED talk.

Indeed, many western publishers have favoured work by African authors that fits racist prejudices about the continent. Writers have been pressured to produce “poverty porn” that presents a clichéd image of Africa as riddled by war, disease and corruption.

In recent years, creative African fiction published globally has offered more nuanced perspectives and tackled broader themes – starting with love.

However, Dream Count makes the point that western literary gatekeepers have not entirely relented. In the novel, Chiamaka pitches her idea for a travelogue about restaurants and nightclubs to a white editor, only to be asked to write a book about rape in the Congo instead. The twist is that this episode occurs in a commercially published African novel whose central theme is … love, explored in all its complicated messiness.

Let this be a reason for cautious optimism.

Daria Tunca is a professor of English Literature, Université de Liège

Top Stories Today