Africa’s refugee camps are plagued by flooding: We looked into drainage systems that can withstand local conditions

Our research found that both engineered wetlands (wetlands created by humans) and pilot-scaled gravity filters (a filter that uses gravity to draw water in and remove pollution) would be able to control floods and improve the quality of floodwater in camps.

Kiran Tota-Maharaj, Royal Agricultural University and Upaka Rathnayake, Atlantic Technological University

More To Read

- South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir tasks new army chief with sweeping military reforms

- South Sudan confirms arrival of eight immigrants deported from US

- Somalia at 65: What’s needed to address its dismal social development indicators

- WFP resumes emergency food airdrops in South Sudan’s Upper Nile State

- From displacement to dignity: Somali IDPs turn coconut waste into livelihoods

- Ethiopia accuses Eritrea, TPLF faction and armed groups of plotting ‘major offensive’

Almost one million people live in 24 camps for refugees and internally displaced people in Ethiopia. They have fled wars and massacres in South Sudan and Somalia, and forced conscription and government oppression in Eritrea.

Life in these camps is difficult. One of the challenges is drainage. The region experiences very intense, short storms. The camps don’t have proper water drainage systems, which means the stormwater causes flash flooding and mudslides. This results in:

- contaminated water flooding out of latrines, waste disposal sites and other unsanitary areas

- damage to clean water points, toilets and sewage disposal systems

- mosquitoes that breed in the stagnant water left behind by floods, increasing the risk of malaria and other illnesses

- severe erosion of roads, preventing aid from being delivered.

This makes an already vulnerable community worse off.

As a group of engineers with about 80 years of collective experience in water, wastewater, environmental engineering, waste management and sustainable engineering practices, we set out to see how we could build something that would drain stormwater into the ground and prevent flash floods.

We built a few different sustainable drainage system models in a laboratory, simulating conditions found in the Lietchuor refugee camp in the Gambella region of Ethiopia.

Our research found that both engineered wetlands (wetlands created by humans) and pilot-scaled gravity filters (a filter that uses gravity to draw water in and remove pollution) would be able to control floods and improve the quality of floodwater in camps.

To move forward, these projects should be set up in the camps and tested fully.

What sustainable drainage systems can do

Sustainable drainage systems are designed to mimic nature’s way of absorbing stormwater when it rains. They all have one thing in common: they slow down and reduce the volume of water that flows rapidly across the surface during a storm.

They often use plants to absorb rainwater, helping recharge the groundwater in the earth. This is crucial in arid and semi-arid regions where people need to rely on wells in times of drought.

Sustainable drainage systems also create green spaces. In refugee camps and humanitarian settlements, green spaces provide shade, improve air quality, and beautify the camp. Greening the camps also creates opportunities for community involvement in their construction and maintenance, fostering a sense of ownership and empowerment.

Many towns and cities worldwide already use sustainable drainage such as green roofs and rain gardens to soak up extreme rain. In Denmark, Copenhagen’s “Cloudburst Management Plan” set up green areas designed to become flood zones when it rains and protect homes in the safe zones nearby. In Taiwan, the Xinhai human-made wetland purifies water and prevents floods.

Research has already found that in Ethiopia, capturing rainwater reduces the amount of stormwater that can cause floods.

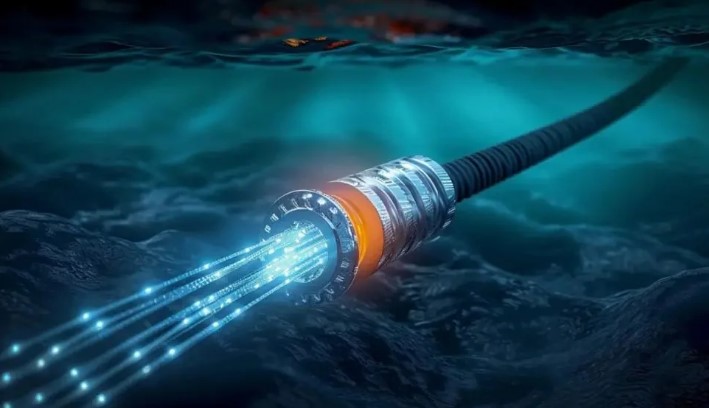

All of the sustainable drainage systems operate in gravity filtration mode – in other words, they use gravity to draw water through a filter. These are some of the sustainable drainage systems that could be built:

Infiltration trenches: these are shallow trenches lined with geotextile membrane, a fabric that can be placed in the ground and filled with rocks, gravel or old pieces of concrete. This allows stormwater to drain gradually into the ground.

Swales: dents or hollows in the ground that absorb stormwater when it rains.

Bioswales: swales that have been planted with bushes to absorb stormwater.

Biofilters: these use different organisms that clean water.

Engineered or constructed wetlands: a perforated drainpipe is inserted into a layer of the coarse sand that is used in concrete mixes. A layer of coal or limestone or gravel is placed over this. Topsoil and plants are added on top.

The leaves and stems of the plants intercept some of the rainfall, slowing down the flow. Rainwater then soaks into the topsoil, keeping the soil moist and helping more plants to grow. The coarse sand helps filter contaminants out of the water, while the gravel at the bottom helps the water seep into the ground.

Constructed wetland models for Ethiopia

We chose to build engineered wetlands and gravity bio-filters because they are effective at absorbing stormwater naturally. They need minimal energy to set up and little maintenance, which is important for refugee camps.

Using inexpensive materials that are available across Africa, we built several engineered wetland models and pilot-scaled gravity filters at the University of Greenwich Medway Campus, School of Engineering laboratories.

We planted the model wetlands with Golden Sweet Flag, a plant which is found in natural wetlands in Ethiopia. Its roots and leaves are able to thrive in consistently wet soil.

Our aim was to find the best way for the wetland to absorb the highest quantity of stormwater so that it did not flood through the camp and to remove the most pollution from the stormwater.

We found that carefully designed constructed wetlands, using locally sourced materials and indigenous plants, effectively absorbed contaminants in the stormwater and significantly reduced pollution.

Next steps

There are practical challenges in implementing sustainable drainage systems in refugee camps, such as limited resources to set them up. However, an initial investment will reduce flood damage and improve water quality over the long term. This is important because refugee camps can be home to people for decades. One Ethiopian refugee camp has existed for over 30 years.

Non-governmental organisations and humanitarian agencies should start exploring all options for using locally available resources and community-based construction techniques.

Refugee communities must be engaged in the planning, construction and maintenance of sustainable drainage systems. Community participation will improve the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of these systems.

Humanitarian organisations, government agencies and research institutions should find more ways of collaborating around systems that will improve life in refugee camps. They also need to run larger-scale pilot projects in refugee camps to see how sustainable drainage systems perform in the rain in the real world.

The Conversation

Kiran Tota-Maharaj, Professor of Water Resources Management & Infrastructure, Royal Agricultural University and Upaka Rathnayake, Professor of Civil Engineering, Atlantic Technological University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Top Stories Today