Expired drugs pile up in county hospitals as patients go without medicine

The Health CS attributed the situation to budget constraints, logistical challenges, and poor prioritisation of pharmaceutical waste management at the county level.

County-level facilities have become hotspots for expired drug stockpiles, with a growing number of hospitals found to be holding unusable medication worth millions, as patients continue to suffer due to a lack of essential supplies.

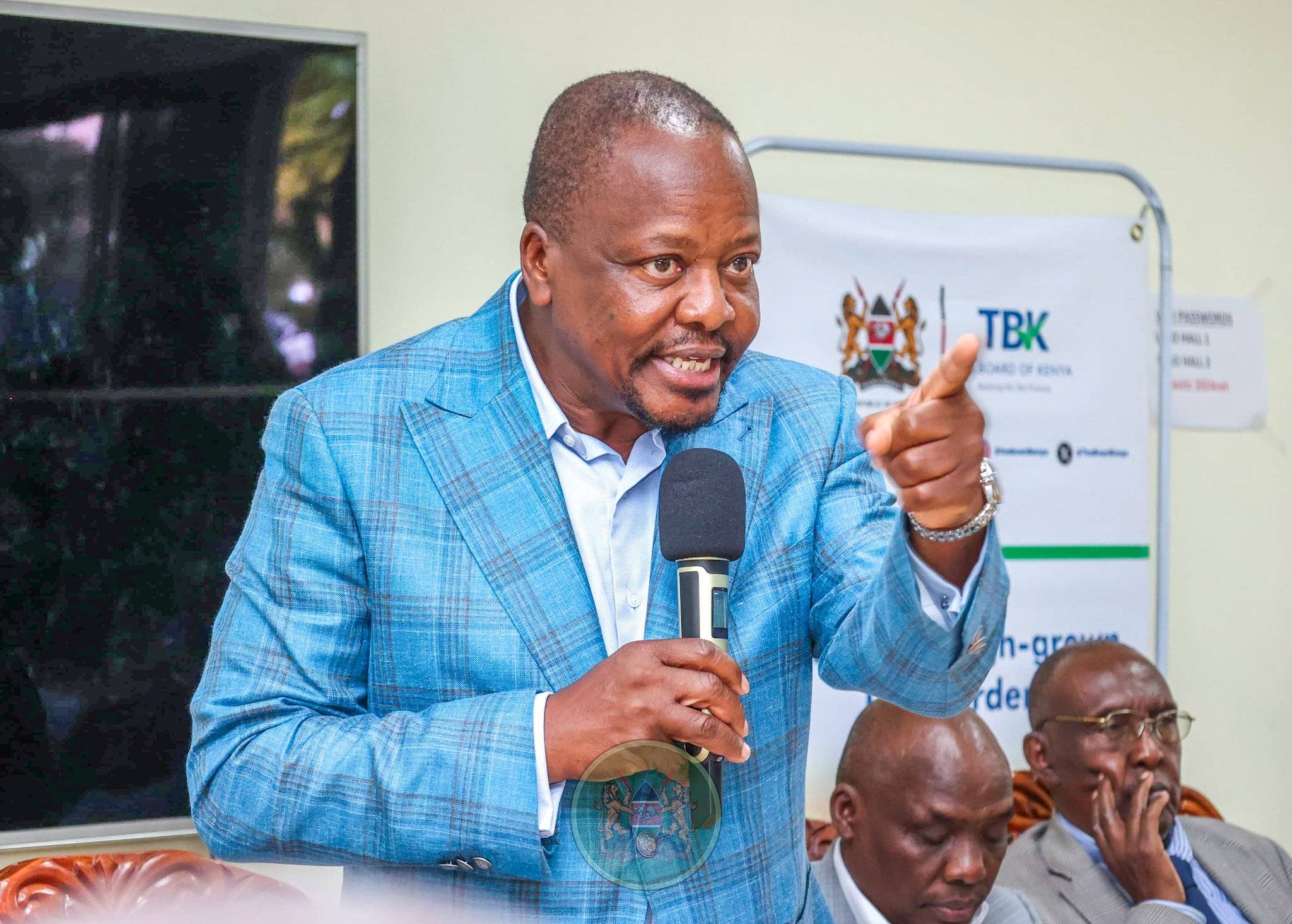

Appearing before the Senate this week, Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale said routine inspections carried out in over 300 public hospital pharmacies, including six national referral hospitals and ten Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA) depots, revealed widespread stockpiling of expired medicine.

More To Read

- Health CS Duale says he will unveil list of fraudulent health facilities on June 14

- Over 900 healthcare workers killed across 36 countries in 2024 - report

- Nurses demand urgent action on poor working conditions as government says it has no money

- Public health facilities to pay KEMSA directly under new SHA system

- Kenya to receive BCG, polio vaccines next month - Health CS Duale

- Kenya invests Sh2.06 billion in vaccine storage to safeguard child health

“A significant number of public health facilities, particularly at the county level, continue to retain large volumes of expired medicines—often beyond the allowable disposal period,” he said.

The Health CS attributed the situation to budget constraints, logistical challenges, and poor prioritisation of pharmaceutical waste management at the county level.

Similar issues were also discovered in several counties, including Nakuru, Trans Nzoia, Kilifi, and Lamu. In many instances, drugs worth millions of shillings are gathering dust in storage rooms while patients are turned away or forced to buy medicine from private chemists.

In Trans Nzoia County, Health Chief Officer Dr Judith Simiyu acknowledged the challenge, saying most of the expired drugs were donated and lacked proper disposal guidance from responsible agencies.

“The bulk of the expired drugs is a result of a change in management guidelines that are usually implemented immediately,” Simiyu told Nation, noting that the county cannot safely dispose of the medication in accordance with regulations.

In Kilifi County, Executive Committee Member for Health Peter Mwarogo said the problem has persisted since before the advent of devolution, especially with drugs received from national programmes targeting tuberculosis, HIV/Aids, malaria, family planning, and neglected tropical diseases.

“Yes, there are expired drugs in the facilities, and many are from national programmes and campaigns, particularly for tuberculosis, HIV/Aids, malaria, family planning, and neglected tropical diseases. The national programmes keep changing the arrangements. When they change, we get a new consignment, and the drugs in the facilities are not used,” he said.

Mwarogo explained that the county is preparing to use a newly constructed incinerator for drug disposal but is awaiting a Sh5 million three-phase power connection and environmental approvals before it becomes operational.

He added that drug usage in the county’s health facilities declined significantly during the Covid-19 pandemic, worsening the stockpiling issue.

“Previously, the Senate Committee on Health found the problem, and the recommendation was that we get rid of the drugs. It is only that we have not been able to do that,” he said, citing the lack of a functional incinerator.

In Lamu County, Deputy Governor and Health Executive Mbarak Bahjaj confirmed that expired drugs remain in storage due to bureaucratic delays.

“We have several boxes of expired drugs still in stores awaiting disposal in facilities like the Mpeketoni Sub-County Hospital in Lamu West,” he said.

The revelations have further exposed loopholes in the pharmaceutical supply chain oversight. Duale told the Senate that his ministry had observed a troubling trend of private pharmacies clustering near public health facilities. He warned that the proximity creates opportunities for unethical practices and systematic theft of drugs.

“This practice creates opportunities for illicit activities, encouraging county staff to steal fresh drugs meant for patients and divert them to private facilities, thereby denying Kenyans access to free medication in public hospitals,” Duale said.

In Nakuru County, an audit by Auditor General Nancy Gathungu found that Nakuru Level Five Hospital had stored expired medicines and medical supplies valued at Sh1.8 million. The hospital, the largest referral facility in the South Rift region, serves Nakuru and six neighbouring counties—Baringo, Nyandarua, Kericho, Narok, Laikipia, and Samburu.

The expired stock, discovered during a physical inspection on October 8, 2024, consisted mostly of antiretrovirals and tuberculosis treatments supplied by international donors. Medical Superintendent James Waweru defended the hospital’s actions.

“We destroyed part of the drugs, but we are still waiting for authorisation to destroy the remaining supplies,” he said, adding that approval from the Global Fund was still pending.

Gathungu faulted the hospital for failing to establish strong internal controls, warning that inefficient procurement planning had led to the acquisition of drugs close to expiry.

“Procurement of drugs that are likely to expire in a short while leads to loss of public resources and, if used, exposes patients in public hospitals to risks,” the audit report stated.

Despite the widespread crisis, some facilities are managing to keep their systems in check. At Coast General Teaching and Referral Hospital in Mombasa, Chief Administrator Dr Iqbal Khandwalla said the hospital maintains strict procurement standards

“We have systems in place to ensure we only procure quality medicines with long shelf lives,” he said.

To address the growing concern, Duale said KEMSA has rolled out several reforms. These include blocking the dispatch of drugs with less than six months’ shelf life unless formally cleared, implementing the First Expiry, First Out (FEFO) protocol to ensure drugs with the earliest expiry dates are used first, and developing tracking systems for timely drug recall and disposal.

Top Stories Today