Between belief and medicine: How traditional remedies shape healthcare choices in Kenya

Traditional medicine is deeply rooted in Kenyan culture, and for good reason. Many herbal remedies offer genuine therapeutic benefits, with modern pharmaceuticals often originating from plant-based compounds.

It’s mid-morning in Digo Majengo, Nairobi, and the neighbourhood is alive with its usual rhythm - pedestrians pass by steadily as local businesses hum with activity.

Ali Ouma, a calm and composed egg vendor, sits beside neatly arranged trays under a canvas shade. He greets passersby with quiet nods and chats occasionally with regular customers.

As he adjusts his eggs, his hand instinctively touches a swelling on his upper gum, a lingering toothache that has caused discomfort for months.

More To Read

- Uganda proposes Bill to regulate medicines, supplements and cosmetics

- Mónica’s story: The woman shipped from Ghana to Portugal in 1556 to stand trial for using traditional medicine

- Why ginger and cloves deserve a daily spot in your kitchen

- Sweet but dangerous: How junk food hooks kids’ brains and fuels lifelong cravings

- Parliament moves to regulate, integrate herbal medicine under proposed KEMRI Bill

- Hold up, humans. Ants figured out medicine, farming and engineering long before we did

Though the inflammation has lessened slightly, the pain remains persistent. Despite this, Ali has not sought hospital care, trusting instead the traditional remedies he has relied on for years.

“I’ve never gone to the hospital,” he says steadily. “I’m my own doctor. I believe in traditional medicine; it works better for me.”

The swelling on his jaw is clearly visible, causing slight facial asymmetry. Ali winces at times but remains firm in his belief. Like many in his neighbourhood, his first choice of treatment is not a clinic or pharmacy but herbal concoctions sold by local vendors or brewed at home from roots, barks and leaves.

Ali swears by mwarubaini, the Swahili name for the neem tree, which he boils into a bitter tea every few days. The tree grows near his neighbour’s compound, and he has used it for years. To him, it is not just medicine but a shield against many illnesses.

“I boil the leaves, drink it, and the pain reduces. Sometimes I feel weak, but after I take it, I feel cleansed,” he explains.

He also prefers dawa ya Maasai, a popular herbal mixture sold in plastic bottles around Nairobi’s settlements. Marketed as a cure-all for stomach upsets, ulcers, H. pylori and chronic fatigue, its ingredients are largely unknown but widely believed to be effective by users.

As we talk, a herbal medicine vendor approaches, carrying a jerrican and small plastic cups. Curious, we ask what its ingredients are. He names a local plant believed to treat stomach aches, ulcers, worms, H. pylori and fatigue.

Ali Ouma, a vendor in Digo Majengo, relies on traditional medication for his health. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Ali Ouma, a vendor in Digo Majengo, relies on traditional medication for his health. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Ali, feeling tired and dizzy recently, requests a serving. A full cup costs Sh50, but having only 20, he receives a smaller portion. Upon drinking it, he winces at the bitterness.

“It’s very bitter,” he whispers, “but it washes all the sicknesses away, including diarrhoea. When you have diarrhoea, it means your body is cleansing itself. That’s why I like it.”

He does not know what the concoction contains, but years of use convince him of its power. “Yes, it causes diarrhoea. That’s normal. But the more you take it, the more it washes the body.”

Traditional medicine is deeply rooted in Kenyan culture, and for good reason. Many herbal remedies have real therapeutic value, with modern pharmaceuticals often derived from plant-based compounds.

But Dr Esther Mwaura, a Nairobi-based health practitioner, warns that not all traditional remedies are safe, especially when used without professional guidance.

“The problem isn’t always the herbs themselves. It’s the lack of regulation. There is no proper dosage, no instructions, and no awareness of possible side effects or interactions,” she told The Eastleigh Voice.

Mwaura cautioned against assuming diarrhoea is always a sign of healing.

“People think it’s cleansing, but it actually strips the body of vital nutrients – vitamins, minerals and fluids. Excessive use can lead to dehydration, weakness or even damage to the gastrointestinal tract,” she said.

She highlighted risks such as internal tears, piles (haemorrhoids) and chronic inflammation caused by repeated forced bowel movements from some herbal mixtures.

“Some patients don’t realise they have blood in their stool or ignore it, thinking it’s normal. But this can indicate serious issues like ulcers or gastrointestinal cancer.”

Mwaura said patients often present only after months or years of herbal treatment, when symptoms have worsened and medical care becomes more complex and expensive.

According to Mwaura, unregulated herbal medicine use can mask serious illnesses, delaying diagnosis and increasing risks of complications. To prevent this, she urged patients to seek medical testing and screening for persistent symptoms.

Not everyone, however, turns to traditional medicine out of ignorance or stubbornness. For many, it is a last resort after the formal healthcare system fails them.

A few years ago, Nassim Hassan developed a painful abdominal growth. She visited hospitals, underwent numerous tests, and followed treatments, but nothing worked.

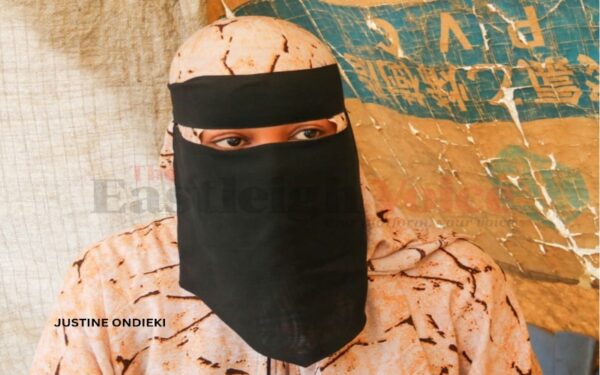

Nassim Hassan shares her recovery after traditional medication led to the disappearance of a painful growth. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Nassim Hassan shares her recovery after traditional medication led to the disappearance of a painful growth. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

“I didn’t know what else to do. I was scared. But nothing helped, until a friend told me about a herbal medicine called 'star',” Nassim recalled.

Reluctantly, she tried it. After a few weeks, her condition improved, and a follow-up scan showed the growth had disappeared. “That’s when I truly believed that when modern medicine fails, traditional medicine can still help.”

Still, Nassim is cautious. She dislikes harsh side effects from some herbal treatments, especially intense stomach upsets, but admits some remedies work even if their mechanisms are unclear. “Everyone just wants to feel better. That’s all we want.”

What concerns experts, however, is that these remedies can mask serious conditions. Someone with persistent ulcers or H. pylori infection may feel temporary relief yet risk worsening illness without proper care.

A study, Understanding Diagnostic Delays for Kaposi Sarcoma in Kenya, involving interviews with 20 HIV-associated Kaposi Sarcoma patients, found that many first sought traditional or herbal treatments before visiting hospitals.

Lack of awareness of disease symptoms, fear of HIV and cancer stigma, and anxiety about invasive procedures delayed diagnosis. Most patients were diagnosed late, limiting treatment options and worsening prognoses.

Similar patterns appear in illnesses such as measles, tuberculosis, stomach conditions, and HIV, where formal medical care is often sought only after symptoms worsen.

Top Stories Today