Unmasking hepatitis: The five types, their causes and treatment

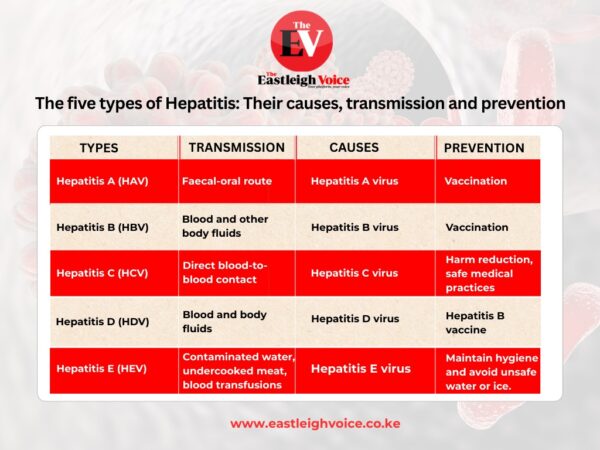

Each type of viral hepatitis differs in terms of how it spreads, the severity of illness, treatment options, and prevention strategies.

Hepatitis, the inflammation of the liver, a vital organ responsible for filtering toxins, processing nutrients and supporting immune function, is often misunderstood as a single disease.

It actually refers to a group of five distinct viruses: Hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Each type varies in its mode of transmission, severity of illness, treatment options and prevention strategies.

More To Read

- Kenya's HIV statistics (2024)

- German researchers find highly effective HIV antibody

- Zambia approves injectable HIV prevention drug

- Viral infections linked to higher risk of heart attacks and strokes

- Male circumcision is made easier by a clever South African invention - we trained healthcare workers to use it

- 'We feel forgotten': People living with HIV decry stigma as US aid cuts bite

While various factors can cause hepatitis, including alcohol use, toxins, and autoimmune conditions, the five viruses are the most common. Here’s a comprehensive look at each:

Hepatitis A (HAV)

Hepatitis A is caused by the hepatitis A virus and is mainly transmitted through the faecal-oral route, often by consuming contaminated food or water, or through close contact with an infected person.

Unlike some other forms, hepatitis A causes only acute infection and does not become chronic. Most people recover completely, although in rare cases it can lead to sudden liver failure, particularly in older adults or individuals with underlying liver conditions.

Hepatitis A is preventable through vaccination, which provides long-lasting protection. Improved sanitation, food safety, and personal hygiene are also key to reducing transmission, especially in areas with inadequate water and waste infrastructure.

Hepatitis B (HBV)

Caused by the hepatitis B virus, HBV spreads through blood and other body fluids.

Common routes include sexual contact, sharing needles, unsafe medical practices, and from mother to child during childbirth (perinatal transmission). The infection can be acute, lasting a short time or chronic, which can lead to long-term complications such as cirrhosis, liver cancer, and liver failure.

Hepatitis B is vaccine-preventable, and the vaccine is widely regarded as safe and effective. The WHO recommends administering the first dose within 24 hours of birth, particularly in areas where perinatal transmission is common.

Hepatitis B is a major global health challenge, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia. Early vaccination, particularly the birth dose, is essential to interrupt transmission and reduce long-term health burdens.

Hepatitis C (HCV)

Hepatitis C is caused by the hepatitis C virus and is primarily transmitted through direct blood-to-blood contact.

Common sources of infection include injection drug use, unscreened blood transfusions, and unsafe healthcare procedures. It can also be transmitted during childbirth and, less frequently, through sexual contact.

Unlike hepatitis A and E, hepatitis C often becomes a chronic infection, and many people remain asymptomatic for years until significant liver damage occurs.

If left untreated, it can progress to cirrhosis and liver cancer. However, modern antiviral therapies can now cure over 95percent of cases, making it one of the few chronic viral infections with a definitive cure.

There is currently no vaccine for hepatitis C, so prevention relies on harm reduction, safe medical practices, and screening programs.

Hepatitis D (HDV)

Hepatitis D, or delta hepatitis, is caused by the hepatitis D virus, which is unique in that it only occurs in individuals already infected with hepatitis B.

It is transmitted through blood and body fluids, and infection can occur simultaneously with HBV (coinfection) or in someone who already has chronic hepatitis B (superinfection).

HDV leads to more severe liver disease than HBV alone, with faster progression to cirrhosis and liver failure.

There is no standalone vaccine for hepatitis D, but it is effectively prevented by the hepatitis B vaccine, since HDV cannot exist without HBV.

Hepatitis E (HEV)

Hepatitis E is caused by the hepatitis E virus and is mainly spread through contaminated drinking water, though transmission can also occur via undercooked meat, blood transfusions, or from animals to humans (zoonosis).

The disease is typically acute and self-limiting, but it can be severe or fatal in pregnant women, particularly during the third trimester. Individuals with pre-existing liver disease are also at greater risk of complications.

According to the WHO, Hepatitis E is a leading cause of waterborne outbreaks in low-resource settings. Its disproportionate impact on maternal health underscores the need for targeted prevention in vulnerable populations.

Hepatitis B, in particular, mirrors HIV in both transmission and treatment. Yet while HIV care is globally prioritised, people living with hepatitis B, over 250 million worldwide

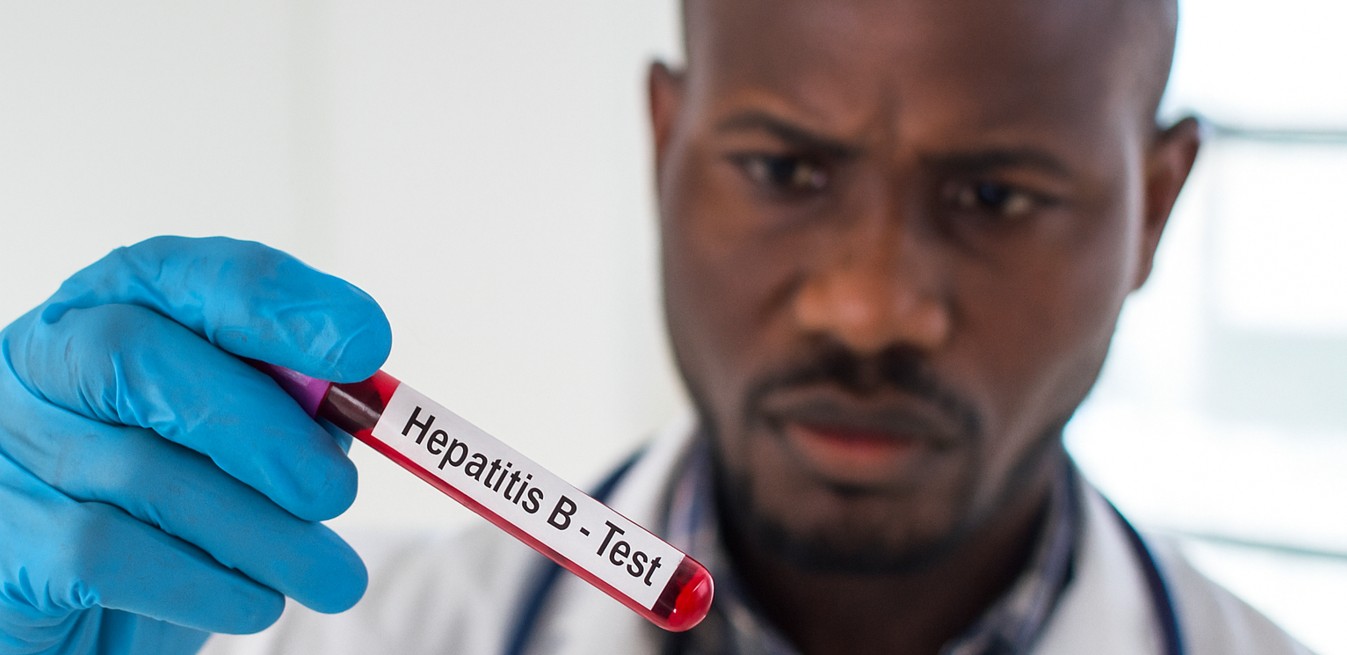

According to Dr Herry Mapesi, a physician and lead medical researcher for Africa at Roche Diagnostics, Hepatitis B and D remain among the most dangerous viral infections due to their strong link to liver cancer.

Dr Mapesi noted that Hepatitis D cannot occur without Hepatitis B; therefore, controlling Hepatitis B through vaccination not only prevents it directly but also eliminates the risk of Hepatitis D infection.

“Many people live with these viruses for years without knowing it,” he explained. “They often show no symptoms until the disease has already caused significant liver damage. The only way to catch it early is through screening. Without it, we risk discovering it too late”

Despite the availability of effective vaccines that can protect individuals for many years, screening and early diagnosis, said Dr Mapesi, remain a significant challenge across much of Africa.

“There is a glaring lack of awareness. Stigma and misinformation are major barriers. Most people don’t know their status. Mothers and children often go unscreened, even during routine care like antenatal visits. While we have made HIV screening standard, hepatitis is often ignored, even though it kills more people annually than HIV/AIDS," said Dr Mapesi.

He emphasised that early diagnosis can prevent mother-to-child transmission during childbirth, stressing the need for greater integration of Hepatitis B screening into routine care, especially during antenatal visits.

“If we can identify Hepatitis B early in pregnancy, we can intervene. Medication in the final trimester can drastically reduce viral load, and birth-dose vaccination for the infant can break the cycle of transmission,” said Dr Mapesi.

He added, “If a pregnant woman is screened and found to have Hepatitis B, we can give her treatment during the third trimester to suppress the viral load. With proper medication, the virus can be controlled, and if the baby receives the first dose of the Hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth, the risk of transmission is virtually eliminated.”

The physician underscored the urgency of the birth-dose vaccine, pointing out that up to 90 per cent of children infected with Hepatitis B at birth may go on to develop chronic liver disease or liver cancer later in life. “Hepatitis B can remain in the body for decades without symptoms. That’s what makes it so dangerous, it’s silent until it becomes deadly.”

Dr Mapesi, however, lamented the lack of public awareness and policy prioritisation, highlighting a critical gap in access despite the disease’s severity.

Dr Herry Mapesi. (Photo: Handout)

Dr Herry Mapesi. (Photo: Handout)

“Hepatitis kills millions every year, yet it doesn’t receive the same spotlight as HIV or tuberculosis. What’s worse is that some of the same medications used to treat HIV, such as tenofovir, are also effective against Hepatitis B. But they remain inaccessible for many patients who do not have HIV but have hepatitis B.”

He went on, “In some countries like Kenya, people living with both HIV and Hepatitis B receive free treatment. However, those who are HIV-negative but have Hepatitis B often have to pay out-of-pocket, even when the drugs are available and already subsidised. This creates an unnecessary and harmful inequality.”

According to Dr Mapesi, there is a difference between HIV and Hepatitis B, despite some shared modes of transmission.

“HIV weakens the immune system, making the body vulnerable to infections, while Hepatitis B primarily attacks the liver, leading to inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, or even cancer if untreated. Both can be transmitted through blood, sexual contact, or from mother to child, but the long-term effects are organ-specific and distinct.”

In terms of treatment, he explained that some antiretroviral drugs used in HIV therapy are also effective against Hepatitis B. This includes tenofovir; TDF (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) and TAF (tenofovir alafenamide). Both are highly effective at suppressing both viruses, though TAF is often preferred for its improved safety profile regarding kidney and bone health.

“We have vaccines that can protect for life. We have effective treatments. What we lack is awareness and equitable access. If we can close those gaps, we can prevent millions of unnecessary deaths and eliminate Hepatitis B as a public health threat.”

Globally, more than 300 million people live with hepatitis, and 1.5 million die every year, most in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. In Kenya, 1.5-2 million people (3-4 per cent of the population) are infected, many unknowingly.

Top Stories Today