Ngaremara mothers rely on goat and cow blood to prevent postpartum haemorrhage

Drinking goat or cow’s blood to control excessive bleeding during childbirth may sound foreign—or even alarming—to many.

But for the Turkana community in Ngaremara, Isiolo County, it is not only a trusted remedy—it is often believed to be the difference between life and death.

More To Read

- How to keep fresh herbs flavourful longer

- Postpartum haemorrhage: How Kenya’s Roaming Blood Bank initiative is saving mothers' lives

- Kenyan mothers turn to herbal remedies to boost breast milk

- How to keep fresh herbs alive and flavourful for longer

- New study reveals why young mothers in Kenya are at higher risk of preterm births

- New hope for mothers as WHO unveils life-saving guidelines to tackle postpartum haemorrhage deaths

Here, where the nearest hospital is hours away, blood banks are often empty, and ambulances are rare, people rely on what is available: a goat or a cow.

In just a few weeks, 20-year-old Paulina Mbayen will welcome her fourth child. Unlike many mothers in urban areas who schedule births around hospitals, Mbayen’s delivery will take place in her manyatta—a small, rounded hut made of sticks, mud, and tin, surrounded by goats and the dry winds of Ngaremara.

There will be no prenatal checkups, no ultrasound scans, no sterile delivery room. Her preparations are simple and rooted in tradition.

Traditional birth attendant

A traditional birth attendant—an elder woman trained by experience rather than textbooks—visits often, gently massaging her belly to assess the baby’s position. After several visits, she gives her verdict: “The baby is facing down. It’s ready.”

But readiness here is about more than the baby’s position. It also involves preparations for what might go wrong.

One of the most important steps is choosing a goat or cow—not for celebration, but for sacrifice. If a mother bleeds heavily during or after birth, the animal will be slaughtered on the spot. Its warm blood, sometimes mixed with fresh milk, is given to the mother to drink. It is believed to restore strength and stop the bleeding—vital in a place where medical help may arrive too late.

At the heart of this tradition is 45-year-old Erupe Ekomoly, one of Ngaremara’s most respected traditional birth attendants. She learned the practice from her mother, who also assisted women at home, and continues the tradition today. Erupe has helped deliver countless children—three of them Mbayen’s—and is ready for the fourth.

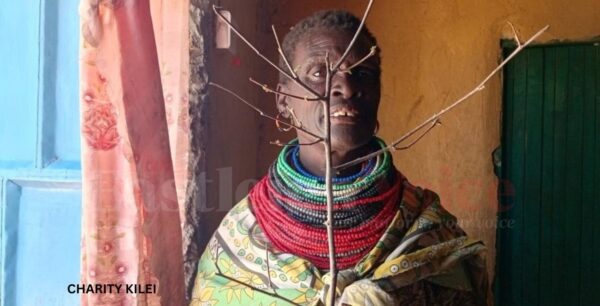

Sabina Amuria Areman, 61, who assist in home deliveries. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Sabina Amuria Areman, 61, who assist in home deliveries. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

“I’ve been doing this since I was a young girl,” she says. “I watched my mother deliver babies. When she passed, the women started calling me.”

Every mother brings a different challenge.

“Some are strong and push with courage. Others are shy, hesitant, or afraid. The ones who fear pushing, we refer them to the hospital. But not all of them can get there in time,” she explains.

Act immediately

Erupe monitors everything—from the baby’s position to the mother’s emotional strength. If bleeding starts, she and other women act immediately: “We tie the mother’s hands and thighs tightly to slow the blood. We give her blood to drink. We boil herbs known by the elders. If nothing works, we call a motorbike. Sometimes it gets here. Sometimes it’s too late.”

Without medical gloves, many now use plastic bags to protect themselves from infections. Yet Erupe always responds when called.

“I don’t ask for money,” she says. “My only prayer is that no woman dies in my hands.”

In Ngaremara, childbirth is sacred—but also harsh. Pain is expected. Fear is kept quiet.

Women in labour are often surrounded not by doctors, but by other women—neighbours, relatives, fellow mothers—who massage, command, and support.

Erupe Ekomoly, a traditional birth attendant. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Erupe Ekomoly, a traditional birth attendant. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Many women feel fortunate when there are no complications, but sometimes the baby is stuck or in the wrong position. If attempts to turn the baby fail, the birth attendant decides whether the mother must be taken to a hospital.

Angata Abenyo, 39, a mother of five, recalls her youngest child’s birth a year ago. As her contractions intensified, blood gushed from her body.

“I had never seen anything like it,” she says, panicked.

Instead of rushing to the hospital, she called the trusted traditional birth attendant, who calmly reassured her: “Everything will be fine.” The baby was delivered safely.

Angata drank goat’s blood, while her upper arms and mid-thighs were tied with herbs—a practice believed to stop bleeding.

“It was scary,” she admits, “but the reassurance and the practice made it bearable.” Having seen the method work before, she trusted it to save her.

Prefers home births

Angata gave birth to her first child in a hospital, but the rest at home. She now prefers home births.

“Here, women hold you. They help you breathe. They press your belly. They help the baby come.”

In Sebra Manyatta, 61-year-old Sabina Amuria Areman has spent most of her life assisting women during childbirth—not as a trained midwife, but as a sister, mother, and friend.

“I can’t sit while another woman suffers,” she says.

She doesn’t deliver the babies, but she boils water, massages backs, fetches herbs, encourages women, and helps tie limbs when bleeding starts. When the situation worsens, she runs for help.

“We’ve had many cases where we had to carry bleeding women to the road just to reach a vehicle. Many times, we had to carry a woman ourselves,” Sabina recalls. “Access to transport during emergencies is a huge challenge. We rely on those with vehicles, but when none are available, we’re doomed.”

More than tradition

For Sabina, these acts are about more than tradition—they are about duty and love.

“We rise for each other,” she says. “Because if we don’t, who will?”

When labour begins, the village moves quietly into action. Women from neighbouring manyattas arrive with pots and firewood. Some boil porridge, others massage the mother’s back, hold her shoulders, and breathe with her. Men are excluded from the birthing space unless a life-threatening emergency requires transport.

“Some women are strong,” says Sabina. “Others are afraid. That fear changes everything.”

In cases of severe bleeding, the steps are immediate: tie limbs, press the stomach, offer blood and herbs, and if all else fails, call for transport to Isiolo General Hospital. But getting there in time is never guaranteed.

Ingesting raw blood

They believe ingesting raw blood helps until the woman reaches a facility. If she dies, they hope it will at least happen at the hospital.

The women of Ngaremara face immense barriers. There is no emergency transport, limited clean delivery equipment, scarce blood for transfusions, and hospital beds are often out of reach. The risk of maternal death is high.

Yet they persist. They deliver each other’s children, carry the bleeding, pray over the trembling, and do what they must with what they have. Birth here is a collective act of courage.

“If we wait, she dies,” one woman says. “She’s losing blood, so we give her blood. We don’t wait. We act. Because if we wait, she dies.”

While these practices are deeply rooted and culturally significant, they are not supported by medical science.

According to Dr Simon Kigondu, President of the Kenya Medical Association, such methods, though well-intentioned, may delay access to the emergency care that truly saves lives.

“When postpartum haemorrhage occurs, it’s critical to understand what is causing the bleeding,” Dr Kigondu explains. “That’s often beyond the scope of most traditional birth attendants, who may lack both the training and the equipment to manage such a condition effectively.”

Pastoralist areas

He acknowledges the realities of pastoralist areas like Ngaremara, where traditional attendants fill gaps left by limited health services, but cautions that relying on unproven remedies such as raw animal blood can be dangerous, especially if it delays hospital care.

“The issue is not just cultural,” he says. “Many rural health facilities lack basic resources—blood, trained staff, transport. This is a national problem, not one unique to Isiolo or Turkana regions.”

He advocates for greater community awareness and education, encouraging more women to seek skilled care during delivery and understand the risks of complications like postpartum haemorrhage (PPH).

Maternal mortality refers to a woman’s death during pregnancy or within 42 days of childbirth due to pregnancy-related causes.

In Kenya, the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) stands at 355 deaths per 100,000 live births—far above the global Sustainable Development Goal target of 70 per 100,000 by 2030. Leading causes include severe bleeding (PPH), infections, high blood pressure disorders, obstructed labour, ruptured uterus, unsafe abortions, and complications from pre-existing conditions such as HIV.

“When postpartum haemorrhage occurs, it’s not enough to simply try to stop the bleeding,” Dr Kigondu says. “You must identify the cause—whether it’s uterine atony, retained placenta, or a tear.”

Herbal treatments

Traditional remedies for PPH, common in rural areas, include herbal treatments, manual techniques, and cultural rituals. Herbs such as bitter leaf, lemongrass, and shatavari are believed to help the uterus contract and reduce bleeding, though scientific evidence is limited.

Manual techniques like uterine massage and placenta removal carry significant risks if not performed correctly.

There are no scientific studies supporting the consumption of blood to reduce PPH.

Current medical guidelines focus on proven methods such as uterotonics (oxytocin, carbetocin, misoprostol), active management of the third stage of labour, and skilled birth attendants to prevent and treat PPH.

Top Stories Today