Woman’s agony of waiting in vain for monthly periods despite having children

![Woman’s agony of waiting in vain for monthly periods despite having children - Abshiro Madina during an interview with The Eastleigh Voice. [Photos: Farhiya Hussein, EV]](https://publish.eastleighvoice.co.ke/mugera_lock/uploads/2024/07/Abshiro-Madina.jpeg)

Madina hopes one day she will get the medical intervention necessary to understand and possibly rectify her condition.

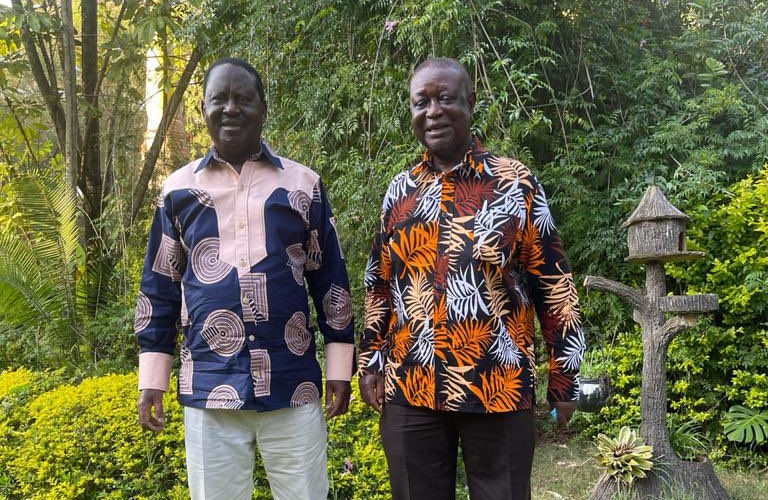

For most women, menstruation is a regular, sometimes inconvenient, part of life. But for 33-year-old Abshiro Madina, the absence of her monthly period for over two decades has been a source of confusion and anguish.

Her story, marked by uncertainty and frustration, reveals the complex interplay between cultural practices, health, and personal identity.

More To Read

- Nowhere to run: How girls escaping harm still find themselves in unsafe spaces

- Male circumcision is made easier by a clever South African invention - we trained healthcare workers to use it

- Unmasked: The truth behind child marriages

- Wajir leaders sound alarm on FGM crisis, call for cultural shift to protect girls

- Scars, blood and silence: The human cost of childbirth in Kenya’s forgotten regions

- Why you should always wash your towels separately from clothes

Madina, a mother of seven, first became aware of her difference in Class Six when her classmates began menstruating. By the time she sat her Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) exams, all her peers had experienced their periods, except her.

She became worried. But she hoped that, like her peers, she would one day experience it.

Nothing happened, and as she proceeded to high school, her worry grew. She confided in a teacher about her lack of menstruation at the age of 16, but was advised to be patient.

"I asked my teacher why at 16 years old I was not having my period. She told me that maybe my time was not due and that I should give it time. By then, all girls I knew had sanitary towels in their bags with. I wanted the same," she said.

Despite her patience, Madina's period never came. This unusual condition made to fear discussing it with other girls, lest they consider her abnormal and distance themselves from her.

In conversations about menstruation, she would contribute based on her knowledge from class, masking her personal confusion and longing.

"I would hear women complain about how expensive sanitary towels were and how girls would stay away from school when they are on their period. I wished I could just wake up and see that blood on my dress. I would walk in that dress with a lot of joy," she said, her voice heavy with emotion.

Madina's condition has also complicated her interactions with medical professionals, particularly during antenatal visits. Without a menstrual cycle, determining her pregnancy stages becomes guesswork for doctors.

"I never know when I’m pregnant. I just start feeling heavy, and when I walk to the hospital after tests, the first question they ask is when I last had my period. They are shocked when I tell them I have never experienced anything like that. They think I don’t even know what they are talking about," she said.

Her quest for a solution has led her to numerous herbalists and traditional masseuses, all to no avail. Madina believes her condition might be linked to the female genital mutilation (FGM) procedure she underwent that went wrong.

Kenneth Miriti, the Reproductive, Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Coordinator at Kilifi General Hospital. (Photo: Handout)

Kenneth Miriti, the Reproductive, Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Coordinator at Kilifi General Hospital. (Photo: Handout)Kenneth Miriti, the Reproductive, Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Coordinator at Kilifi General Hospital. (Photo: Handout)

"Maybe they interfered with some nerves or something happened during that time that caused all this. I have a lot of questions in my mind, but all I want is the experience of menstruating like other women," she said.

Interestingly, Madina sometimes experiences symptoms akin to menstruation, such as a red face, fatigue, tender breasts, bloating, mood swings, and headaches. However, these symptoms dissipate without the onset of a period.

Now a teacher to over 100 children, Madina finds herself in the unique position of educating others about menstrual hygiene and cycles she has never personally experienced. Her hope remains that one day she will get the medical intervention necessary to understand and possibly rectify her condition.

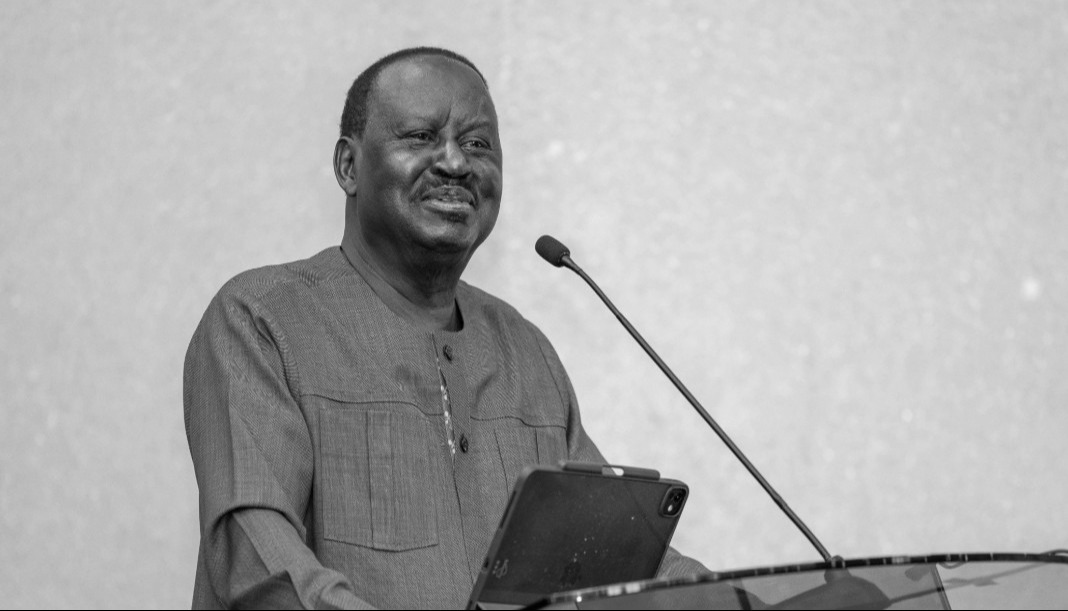

Kenneth Miriti, a reproductive, maternal, child, and adolescent health coordinator at Kilifi General Hospital, acknowledged that Madina's condition requires proper evaluation.

"FGM is not an internal issue that it can cause amenorrhea unless the procedure was very severe and affected the entire vagina, which could be very serious," he said.

He noted that such cases might occur with type three FGM, where the vaginal introitus is closed, necessitating complex surgical procedures like vaginoplasty and mega urethra plication for reconstruction.

Miriti described Madina's case as one that demands scientific research to understand her ovulation and determine the appropriate medical assistance. However, he warned that such operations can be costly due to their complexity.

He said the challenges of underreporting in communities practising FGM, complicate the gathering of reliable data.

“Communities that practice FGM are very secretive. Most times they don’t even deliver in hospitals. They prefer home delivery carried out by the traditional surgeons who most likely circumcised them," he said.

This secrecy means many women suffer in silence, making rapid sensitisation and outreach programmes essential.

He said Madina’s story underscores the importance of addressing hidden health issues within marginalised communities, providing them with the support and medical care they need.

For Madina, the hope of one day experiencing a menstrual cycle remains a distant, but deeply held wish.

Top Stories Today