Unmasked: The truth behind child marriages

Globally, the numbers are staggering: over 640 million women alive today were married as children, and 12 million girls are still married each year - that's one girl every three seconds.

In March 2025, the tragic case of Gaala Aden Abdi, a 17-year-old girl from Wajir County, shocked the nation.

Gaala was reportedly killed for resisting a forced marriage to a 55-year-old man. She was buried under suspicious circumstances, and her remains were burned beyond recognition.

More To Read

- Parliament to debate Bill ending private settlements in SGBV cases

- KNCHR raises alarm as over 100 femicide cases recorded in three months

- 16 days of activism: Strengthening protection against gender-based violence

- Violence against women and children is deeply connected. Three ways to break the patterns

- Man charged with schoolgirl’s murder shocks court, seeks plea deal

- Why a woman is killed every 10 minutes; the rising wave of global femicide

The case is in court, but her story has become a symbol of the deadly cost of child marriage in Kenya, a practice that, despite legal bans, continues to steal girls’ futures and, in some cases, their lives.

For the tradition’s custodians, the birth of a girl is met with quiet satisfaction, not from love or pride, but because she represents future wealth.

To them, she symbolises cattle, land, or money - assets to be exchanged once she reaches puberty.

But for mothers cradling their newborn daughters, it is a moment tinged with sorrow and fear. They know what lies ahead.

Milcah Cherotich remembers the day it happened, one moment laughing with her best friend, the next her world was shattered.

Without warning, warriors appeared. In a blur of violence, her friend was grabbed, screaming and kicking, thrown over the shoulder like cargo, and not a child.

The most terrifying part? No one acted. No one resisted. It was as if everyone accepted this was just how things were.

Cherotich, a frightened schoolgirl, was frozen in disbelief. Her friend, who dreamed of finishing school and a future, was torn away, never to return.

Desperate, Cherotich ran to relatives for help, expecting outrage, but, instead, met quiet acceptance.

“Why are you upset? She’s starting her own family,” they said, as if her abduction was cause for celebration.

She realised that in Turkana County, like many pastoralist communities, child marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM) are not seen as abuses, but tradition.

Her friend’s pain was invisible to those who had walked the same path. This was just how things had always been. She often asked herself: “Why should a 12-year-old girl be seen as a bride?”

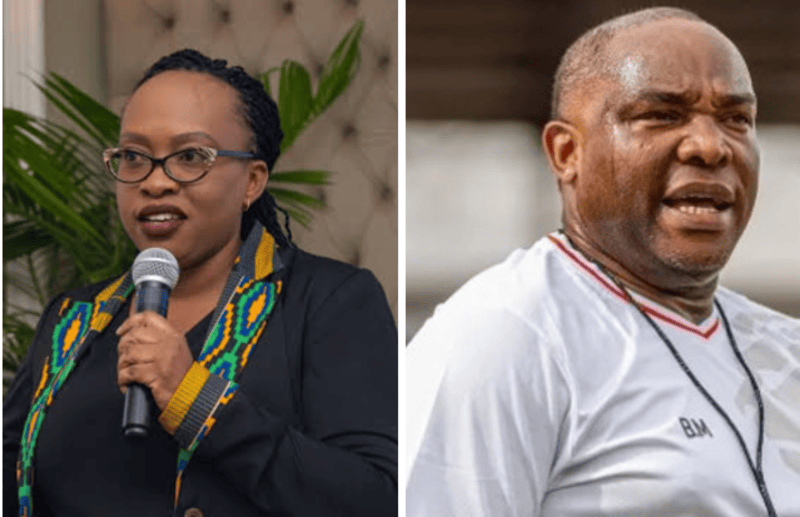

Milka Cherotich speaks during the screening of 'Nawi'. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Milka Cherotich speaks during the screening of 'Nawi'. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Other Topics To Read

To her, it was never culture; it was pedophilia disguised as tradition. Yet when she spoke out, she met silence, resistance, and the heavy hand of custom. “It could have been me,” she thought, her voice trembling.

That day, something inside her broke... and something else awoke, a fierce will to fight back.

Years later, she visited that friend again. The hopeful girl was gone. In her place stood a mother of three, her spirit crushed, her eyes dimmed. “She was happy I made it, but I saw the pain behind her smile. She had lost hope. That broke me.”

In that moment, Cherotich made a vow - she might not save her friend, but she would fight for the daughters. For every girl waiting to be heard, protected, and free.

From that pain, the story of Nawi was born. The film tells the story of a 14-year-old forced into marriage who died giving birth, a tragedy repeated too often in Kenya.

Inspired by real girls and true events, Nawi, which is now screening in counties across Kenya, symbolises countless stolen lives. It reminds us why the fight matters: girls deserve childhoods, not brideships. They should never be punished for being born female.

“Pedophiles are hiding behind culture. What tradition teaches a man to desire a 12-year-old? That’s abuse, not culture,” said Cherotich. “It’s time the government acts, not with words, but with real accountability.”

In an effort to stir change, Cherotich has begun community screenings of Nawi, targeting men, through a partnership with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and government agencies, among others.

Speaking to The Eastleigh Voice, she recalled a man who married off his daughter, who, after watching Nawi, asked, “Is this what really happens in our community?”

The man saw his daughter reflected in Nawi, and something changed in him.

These moments fuel her resolve. But the work is far from done. Many girls flee FGM and forced marriages, but lack safe spaces and support.

“People know FGM leads to marriage. Girls run to save their lives, but where can they go?” posed Cherotich.

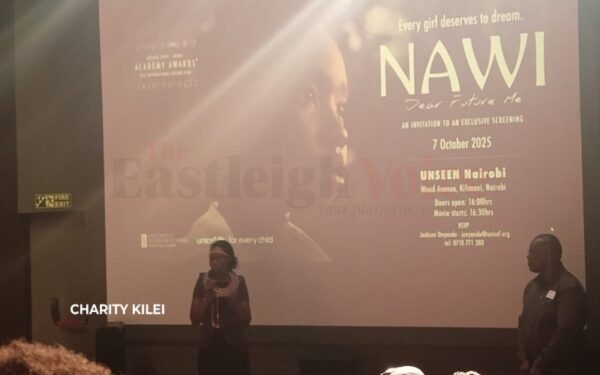

Ahead of the International Day of the Girl on 11 October 2025, UNICEF and the Children's Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) jointly hosted a screening of “NAWI: Dear Future Me” in Nairobi. This event was organized to reinforce the collective commitment of various partners to this year’s theme: “The girl I am, the change I lead: Girls on the frontlines of crisis.”

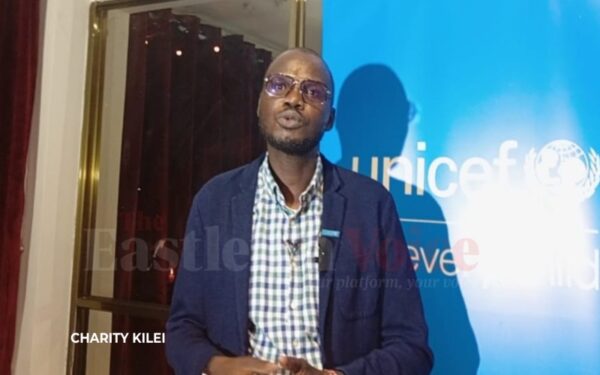

According to Jackson Onyando, UNICEF-Kenya child protection specialist, progress exists, but regional disparities show a complex reality.

Nationally, 13 per cent of women aged 20 to 24 were married as children, down from 23 per cent. Yet in Turkana County, where Nawi was filmed, rates reach 26 per cent, and in northern regions even 40 per cent, with many married before 18.

Child specialist with UNICEF, Jackson Onyando. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Child specialist with UNICEF, Jackson Onyando. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

“Progress must be understood in local contexts,” Onyando explained.

Onyando stressed the need for county-level programs tailored to unique challenges. In pastoralist areas, child marriage persists openly and secretly, driven by poverty, harmful gender norms, and crises like drought.

Kenya’s laws against child marriage are strong but inconsistently enforced. Many communities remain unaware of or ignore the laws, and enforcement is weak.

“Child marriage has always been illegal, but laws alone aren’t enough,” Onyando said. “Enforcement alone leads communities to hide the practice, silencing the girls.”

He noted that changing deep-rooted norms will take time and inclusive efforts, and men must be part of the conversation, not just participants, but decision-makers.

“We need programs targeting boys and men, they often decide when and whom a girl marries,” Onyando added.

He warned that without addressing economic shocks and gender inequality together, the cycle will continue. During hardship, families see daughters as assets for survival when livestock is lost.

To mitigate, UNICEF promotes education to keep girls in school, reducing early marriage. Girls dropping out are far more likely to marry young, making retention crucial.

Its programs support families with cash transfers and social protection during crises, providing alternatives to harmful practices.

Top Stories Today