Risks of high-fiber diets for young children -Expert

When it comes to introducing new diets, parents often adopt different methods depending on their lifestyles. Many make these choices without thoroughly researching their potential effects, and only a few seek advice from nutritionists about suitable foods.

In today’s busy schedules and long days at school and home, many families choose a hearty breakfast, typically rich in processed fibre and often including cereal, as a practical and popular solution.

More To Read

- Parents lead the fight against malnutrition as Turkana’s ACCEPT project shows big results

- MSF raises alarm over extreme malnutrition as Sudan crisis deepens

- 5.7 million people face food insecurity in Haiti

- WFP warns of rising hunger among refugees in Ethiopia

- Child malnutrition in Kenya: AI model can forecast rates six months before they become critical

- Nairobi Trade Fair puts spotlight on innovation as Kenya braces for rising hunger fears

While cereals can be beneficial, young children process high amounts of processed fibre differently than adults. Without proper monitoring, this may lead to various health issues.

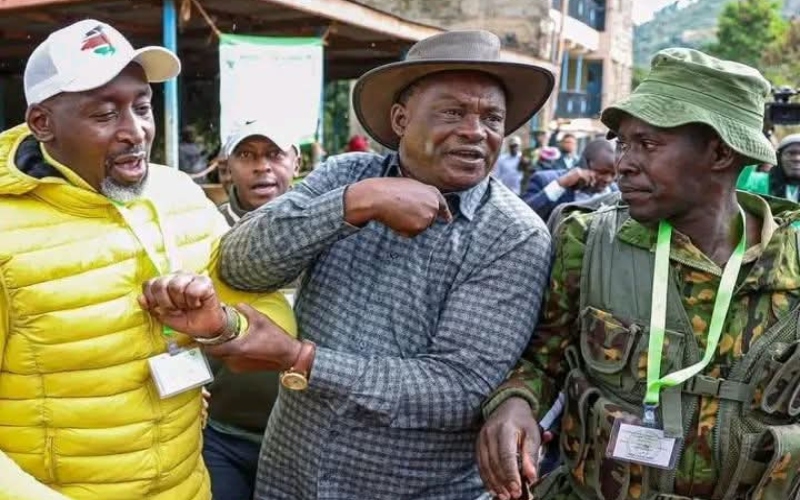

Micah Mwangi, a nutritionist in Nairobi, warns about the rising concern of mismatched weight and height among young children. “We are seeing cases where children's weights do not align with their heights, which can be an indicator of potential issues.”

Mwangi points out that introducing high-fibre foods to children, especially those under three years old, can lead to malnutrition and underweight problems. “When children are given too much fibre too early, it can affect their ability to process food and reduce their appetite. This can result in them not feeling hungry and potentially becoming underweight.”

It's important to be cautious if you notice your child becomes grumpy or rejects meals after eating cereals or processed foods high in fibre.

“Fibre may help adults feel full longer, but applying the same principle to children by giving them excessive fibre can be counterproductive. It can lead to them eating less and possibly becoming underweight.”

Mwangi warns that if a child eats less food during mealtimes or becomes fussy after consuming fibre-rich foods, it could indicate the need to adjust their diet to ensure proper nourishment and growth.

"When you notice that a child's weight does not align with their height, it may indicate either overweight or underweight conditions. Both extremes are problematic: being overweight can increase the risk of diabetes while being underweight can make the child more susceptible to various illnesses."

When a child does not receive a balanced diet, they are at risk of undernutrition, which is characterised by an inadequate intake of energy and nutrients necessary for maintaining good health.

Malnutrition occurs when the body lacks essential nutrients. This can result from a poor diet, digestive disorders, or other illnesses. While refined products can provide a quick source of energy for children, they may contribute to obesity.

The World Health Organisation explains that weight-for-age measures a child's body mass relative to age. If a child is deemed underweight for their age, it indicates they have either not gained enough weight or have lost weight. This measure considers both weight and height, reflecting both past (chronic) and present (acute) malnutrition. It also helps assess overall health and nutritional risk within a population.

Undernutrition encompasses four primary forms: wasting, stunting, being underweight, and deficiencies in vitamins and minerals. It notably increases the risk of disease and death, particularly among children.

Wasting, identified by low weight-for-height, typically indicates recent and severe weight loss due to inadequate food intake or illness, such as diarrhea. Children who are moderately or severely wasted are at a higher risk of death, but treatment options are available.

Stunting, identified by low height-for-age, results from chronic or recurrent malnutrition. This condition is often linked to poor socioeconomic conditions, inadequate maternal health and nutrition, frequent illnesses, and improper feeding and care practices during early childhood. Stunting can impede a child’s physical and cognitive development.

Other Topics To Read

Underweight children have a weight-for-age that is lower than expected. An undernourished child may also be stunted, wasted, or experience both conditions.

Globally, malnutrition is responsible for 52.5% of deaths among young children, with this percentage varying by cause. For instance, it accounts for 44.8% of deaths related to measles and 60.7% of those related to diarrhoea.

According to UNICEF, over a quarter of children under the age of five in Kenya—approximately two million children—experience stunted growth, the most prevalent form of undernutrition in this age group. If not addressed, stunting can have severe, long-term impacts on both mental and physical development. Additionally, 11% of children are underweight, and 4% are wasted. Both wasting and severe wasting are linked to an increased risk of preventable deaths among young children.

Top Stories Today