Kamukunji's quiet triumph: How community effort revitalised a historic Nairobi space

For now, though, Kamukunji Grounds stands as a quiet triumph—a model of what happens when a community decides to reclaim and reshape its own spaces.

At 55 years old, Tom Mboya Rapudo has witnessed the transformation of Kamukunji Grounds with his own eyes—literally from the ground up.

Living in Shauri Moyo, a densely populated part of Nairobi near Majengo, Rapudo recalls when Kamukunji Grounds was nothing more than an overgrown patch of land.

More To Read

- Rising stray dog population in Kamukunji spark public health and safety concerns

- Kamukunji faces vaccine crisis as over 12,000 children miss routine immunisation

- Residents of Eastleigh’s Seventh Street demand urgent road repairs

- 175 Kamukunji youth receive business equipment from President Ruto to boost employment and income

- Safaricom’s Ndoto Zetu initiative elevates maternal health in Kamukunji's Eastleigh with bed donation

- Creativity in crisis: Kitui village artisans fight to save Nairobi’s craft heritage after market fire

"For the longest time, it was just a bushy thicket," he says. "It wasn't a park. It was a dangerous no-man's land where only the desperate dared to rest."

Despite its overgrown and neglected appearance, Kamukunji Grounds always attracted people, mainly men and children. Men came seeking a brief escape from cramped homes or strenuous work, and children came to play on open stretches of grass. But there was always a sense of danger hanging in the air. Muggings were frequent, and many who closed their eyes for a nap often woke up without their phones or wallets.

That grim history began to change around 2020, when local community groups, in partnership with Nairobi County authorities, launched a major revitalisation initiative. Today, Kamukunji Grounds is nearly unrecognisable from the untamed space it once was.

The area is now divided into two distinct sections: a fenced, well-maintained park adorned with trees, benches, and walkways, complete with security guards and regular cleaning. and an open, unfenced area, still frequented by many homeless individuals and those unable to pay the modest entry fee.

Rapudo, who once used to nap in the unsafe open areas, now finds peace inside the fenced section. For just Sh20 a day—less than a cup of tea—he gets access to a clean, secure environment.

"I come here almost every day after work," he says. "Sometimes, there's no plumbing work, and staying home alone in that heat makes you feel worse. But here, I can breathe, I can rest, and I can watch life go by."

His bond with the park grew even stronger after a personal tragedy, after he lost his wife. The grief, he says, left a void he couldn't fill. Choosing not to remarry, he found himself drifting into isolation.

"Sitting in that house alone was too much," he confesses. "But here in the park, even if I'm not talking to anyone, I don't feel alone. Children are laughing, people playing checkers, the rustle of trees... It reminds you that life goes on."

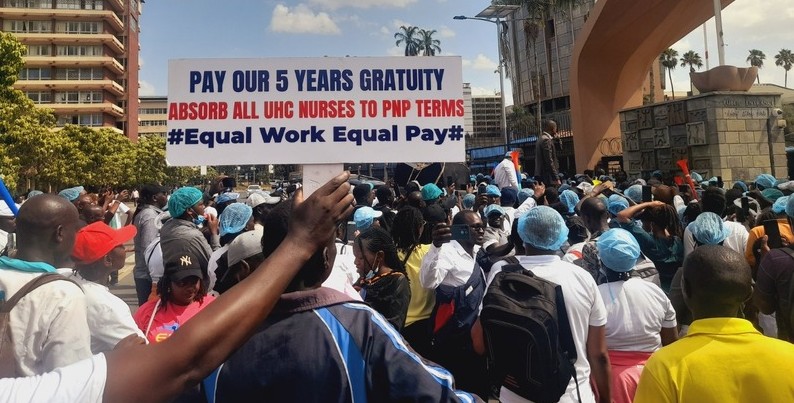

People relaxing at the historic Kamukunji Grounds. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

People relaxing at the historic Kamukunji Grounds. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

For Rapudo, Kamukunji Grounds is more than a park—it's a space for emotional healing, for mental rest, and for rebuilding a sense of belonging. Over time, the park attendants have come to know him well. Sometimes, they even waive the Sh20 fee, recognising him as one of their own. "It's like a second home now," he smiles.

Rapudo isn't the only one who treasures the park. John Munene, a young man in his 20s, works as a loader at the nearby Gikomba Market. His day begins well before sunrise—at 3 am, to be precise. By 7 am, his shift is over, and he's often physically exhausted. Instead of going back to his cramped one-room house, he heads to Kamukunji Grounds.

"This park has changed everything for 20 bob, you get peace, you get trees, you get safety. That's all a man really wants after a long shift."

He adds that the space isn't just for sleep or rest. On many days, you'll find children running about, hawkers selling tea and snacks, and groups holding small meetings or table banking sessions known as chamas.

The transformation of Kamukunji Grounds did not happen by chance. Mohammed Kioko, vice-chairperson of the Kamukunji Environmental Conservation Champions (KECC), explains that it was the result of determined local effort in partnership with various organisations. Recognising how many residents depended on the space—and the need for children to have a safe place to play—the community came together to fence off a section of the park, plant trees, and improve security.

"We noticed the park was becoming more popular," he says. "People were coming to rest, to breathe, especially those who work night shifts. We introduced the Sh20 fee not to make a profit, but to help maintain the place—pay for cleaning, water, and the security guards who keep it safe."

Mohammed Kioko, vice-chairperson of the Kamukunji Environmental Conservation Champions (KECC). (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Mohammed Kioko, vice-chairperson of the Kamukunji Environmental Conservation Champions (KECC). (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Even small-scale vendors are allowed to hawk tea and snacks inside the park, at no extra charge beyond the Sh20. It's a model based on trust, respect, and shared responsibility.

The revitalised space now hosts couples, church groups, chamas, and young people looking for quiet moments away from the city's chaos. It's become a rare oasis in a concrete jungle.

But Kioko acknowledges that challenges remain. "There are still homeless people who sleep in the unfenced areas," he says. "We don't turn anyone away, but we try to discourage idlers who cause trouble. That's why we want to fence the whole park eventually—to make it safer, more beautiful, and more inclusive."

For now, though, Kamukunji Grounds stands as a quiet triumph—a model of what happens when a community decides to reclaim and reshape its own spaces.

It's a place where the weary can lie down without fear, where the lonely can find quiet company, and where hope, quietly but surely, takes root under the shade of newly planted trees.

The revitalisation of Kamukunji Grounds has been a collaborative effort involving various organisations, including Public Space Network, KECC, SHOFCO, alongside the dedicated advocacy of Kamukunji MP Yusuf Hassan.

Eight years ago, the area MP Yusuf Hassan proposed designating the grounds as a national protected monument, emphasising its historical significance. In a motion presented to the National Assembly, he highlighted that despite its crucial role in Kenya's political history, the grounds had been neglected and allowed to deteriorate.

The restoration work officially began in 2020, following the challenges brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Over 19 self-help groups came together to form the Kamukunji Environmental Conservation Champions (KECC), to rehabilitate the park and create a space the community could enjoy and take pride in.

Today, the park welcomes hundreds of visitors daily, including children. It now features a dedicated mental health corner and serves as a safe, open space where people can relax, socialise, and find much-needed respite.

Top Stories Today