“It’s like killing culture” Human Rights impacts of relocating Tanzania’s Maasai

The government has provided relocated NCA families with a house and about two to five acres of land to farm, in addition to constructing and renovating roads, a primary school, a dispensary, post office, police post, water supply system, electricity, and cellular network to service Msomera.

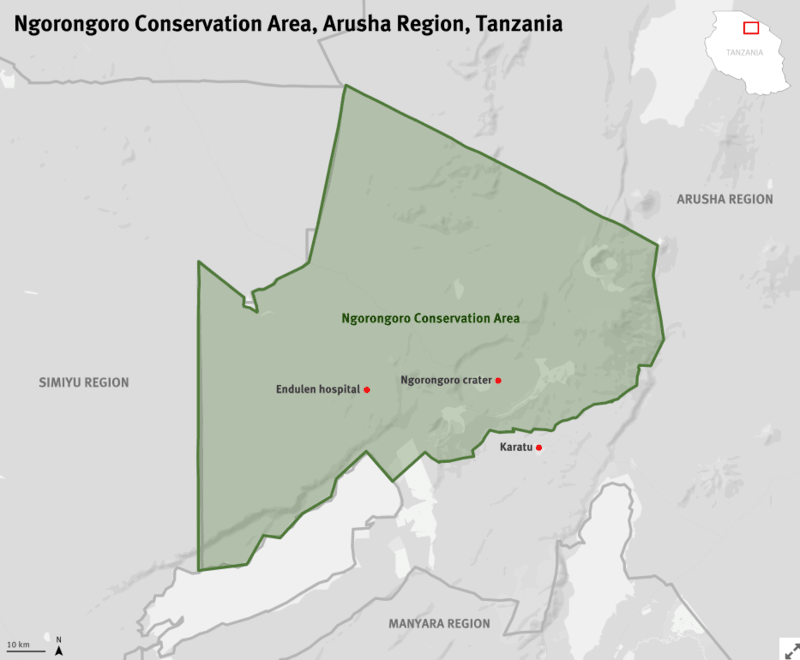

The Tanzanian government by 2021 had devised a plan to relocate about 82,000 Maasai people from their homes and ancestral lands in Arusha region’s Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) by 2027.

The British colonial government had established the NCA, a so-called multiple land use area, in 1959 to create a permanent homeland for the people who lived in and around the Ngorongoro Crater, the vast majority of whom are Indigenous Maasai herders.

More To Read

- Tanzania slams Human Rights Watch report as “false and misleading” ahead of 2025 elections

- 127 civilians killed by IS Sahel in Niger since March - Human Rights Watch

- DCI refutes harassment claims by Human Rights Watch official Otsieno Namwaya

- Human Rights Watch official Otsieno Namwaya says police target him instead of rights abusers

- Rwanda calls Human Rights Watch's count of new graves at military cemetery "disrespectful"

- KHRC raises alarm over police surveillance of Human Rights Watch official

In 2022, the government began to systematically reduce the availability and accessibility of essential social services for the residents of the NCA, including by defunding institutions providing those services.

At the time, social services in the region were already significantly reduced, less accessible and of generally poorer quality than those elsewhere in the country. The authorities also took steps to restrict residents, who depend primarily on herding livestock for their income, from grazing animals in specified areas of the NCA.

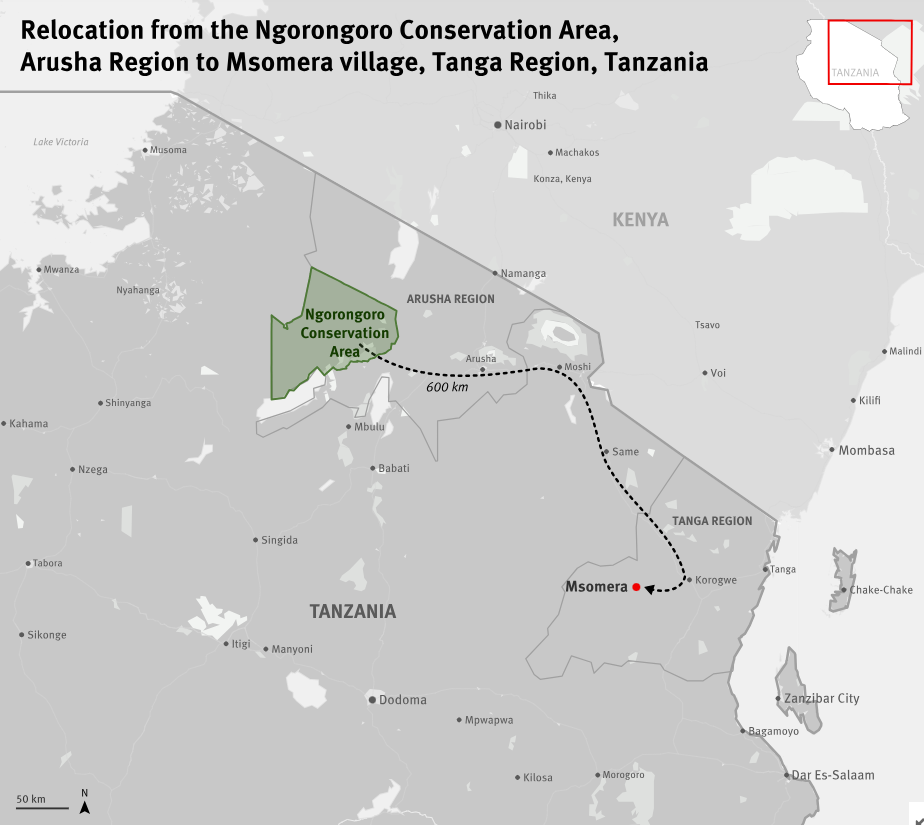

With little or no consultation with affected communities, the government has since resettled and based on its resettlement plan, will continue to relocate people from the NCA to Msomera village in Tanga region’s Handeni district, about 600 kilometres away.

The government has provided relocated NCA families with a house and about two to five acres of land to farm, in addition to constructing and renovating roads, a primary school, a dispensary, post office, police post, water supply system, electricity, and cellular network to service Msomera.

Between August 2022 and December 2023, Human Rights Watch interviewed nearly 100 people—including NCA residents facing relocation, former NCA residents who have been resettled in Msomera, and existing residents of Msomera—and found that what the government has referred to as its “voluntary relocation plan” from the NCA has been far from voluntary.

In implementing their plan, authorities have used tactics that amount to constructive forced eviction in violation of international human rights law and standards. Forced evictions constitute gross violations of a range of internationally recognised human rights, including the human rights to adequate housing, food, water, health, education, work, security of the person, freedom from cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, and freedom of movement.

In resettling those relocated from the NCA, authorities have also effectively evicted residents of Msomera by constructing buildings and other infrastructure, and allotting houses and farmland to the displaced, on land that was already occupied and used by local residents.

A group of Maasai women and men in traditional Maasai clothing and jewelry near Endulen, Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. (Human Rights Watch)

A group of Maasai women and men in traditional Maasai clothing and jewelry near Endulen, Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. (Human Rights Watch)

The government has not sought the free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) from the Indigenous Maasai residents of the NCA. Community leaders said they were not properly consulted about the government’s resettlement plan, nor did they have access to information on matters related to the relocation process, compensation, what conditions to expect in Msomera, and which villagers were registered for relocation.

The lack of free, prior and informed consent meant the authorities have not addressed concerns of residents, and residents have not been given the possibility of engaging with authorities to mitigate harm or protect their rights, whether they choose to relocate from the NCA or remain.

Of particular concern to residents are government measures that are forcing residents out of the NCA. These include the scaling-down of essential infrastructure, including education and health services, restrictions on movement in and out of the NCA, reduced access to pasture, water, and cultural sites, and government-employed rangers assaulting and beating residents with impunity.

The authorities also did not consult Msomera residents on the resettlement plans. Without any input from the affected communities, the government mapped out and built houses on land where Msomera residents have lived and grazed their cattle for decades, forcing them out of the area.

These residents have clashed with the newly resettled families from the NCA as access to land for cultivation and pastoralism and to other resources has become increasingly limited. When those already living in Msomera have protested loss of their land, the authorities have threatened them with eviction and arrest.

Maasai who relocated from the NCA to Msomera, a decision some said they made because of government restrictions that made life extremely difficult, struggled as well. One such restriction is that only the head of household, usually understood to be male, registers the family to relocate, thus taking women out of the decision-making process.

This exclusion has contributed to a resettlement process that does not reflect the complex nature of Maasai households, many of which are polygamous, multi-generational, and multi-household. Also, the houses provided by the government have not met the cultural needs of many households as some new homes are too small for large, multi-generational, multi-household Maasai families.

In Msomera, each male head of household is provided one house for his family, but Maasai culture does not permit multiple wives to live in the same house with him.

Consequently, some families have had to use some of the insufficient compensation they received from the government to build additional houses to accommodate wives and larger families and to prepare land for their animals. Some of the relocated people also expressed concerns about having less access to quality water than they did in the NCA.

Mokilal village office, local government authority, with no roof in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. (Mathias Rittgerott/Rainforest Rescue)

Mokilal village office, local government authority, with no roof in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. (Mathias Rittgerott/Rainforest Rescue)

The government has systematically silenced critics of the relocation process, contributing to a climate of fear among residents and local human rights defenders. Many critics have not spoken out for fear of reprisals from the authorities. The authorities have arrested community activists and denied civil society organisations entry into the NCA. Human Rights Watch found that those allowed in have been closely monitored by government rangers. These restrictions and fear of government retaliation have deterred civil society groups from raising awareness about the relocation process and the human rights abuses against affected communities.

Through its relocation process, Tanzania has violated numerous rights of Maasai residents and their communities in the NCA and of Msomera residents, as codified in regional and international treaties ratified by Tanzania, including the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). The Maasai and other Indigenous peoples are also protected by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). International human rights law protects the rights of the Maasai and other rural rights-holders to, among other things, property and land, participation, information, freedom of expression and freedom of assembly, education, and the highest obtainable standard of health.

Maasai communities in the NCA are specifically protected by Tanzanian laws, including the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Ordinance of 1959 and subsequent amendments, the Land Acquisition Act of 1967, the Land Act of 1999, and the Village Land Act of 1999, that recognise their legal status within the NCA, rights to customary land, consultation, and compensation.

The government of Tanzania should immediately halt the relocations of residents from the NCA. The authorities should meaningfully consult all affected communities in the NCA and seek the free, prior and informed consent of affected Indigenous communities. They should also meaningfully consult affected residents in Msomera. Those who consent to be relocated should receive adequate compensation based on their informed consent.

The government should reinstate funding and other resources for social services that have been decreased or transferred out of the NCA in violation of the rights of affected communities, including for education and health care. It should also create an independent alternative grievance and redress mechanism that can process complaints of and provide remedies for human rights violations related to these relocations.

Glossary

Game-Controlled Area (GCA): Locations designated under Tanzanian law that the president may set aside for biodiversity conservation, to preserve wildlife populations, promote tourism, and generate revenue through controlled hunting activities. Unlike game reserves, on GCAs, people can live, cultivate, and keep livestock unrestricted.

Indigenous peoples: The rights of Indigenous peoples are addressed in United Nations and African standards. Under international law, Indigenous peoples are ethnic and cultural groups with deep connections to their traditional lands and resources. They have distinct rights outlined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, including the right to self-determination, control over their lands and resources, and protection of their cultures and languages, and governments are obliged to ensure their free, prior and informed consent in decisions affecting them.

Multiple Land Use Area: In the context of conservation in Tanzania, a “multiple land use area” is a region where conservation efforts should be balanced with sustainable human activities. They aim to protect biodiversity, natural habitats, and wildlife while allowing for responsible resource use and human settlement.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA): The NCA, conterminous with Ngorongoro division, is a protected area and a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Tanzania’s northern Ngorongoro district.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority (NCAA): The NCAA is a parastatal body under Tanzania’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism set up to manage the NCA.

Ngorongoro Pastoral Council (Pastoral Council): The Pastoral Council, which was legally recognised in 2000, functions as an intermediary body connecting the local NCA community with the NCAA. It comprises representatives from the NCA Wards and Villages, offers advice to the NCAA Board of Directors, and possesses the authority to devise and propose projects for approval by the NCAA such as scholarships for students, construction of school buildings, and creating dams and boreholes.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Tanzania

On Protection of Land Tenure

Respect the human rights, including land and tenure rights, including traditionally-owned and communal land, of Indigenous people and other rights holders in developing and implementing all conservation measures.

Legally recognise the lands and resources that pastoralist communities in Ngorongoro district have used and managed for generations, with due respect for their legal systems, traditions, and practices, including traditional grazing methods and rituals.

On Free, Prior and Informed Consent and Participation

Adequately consult and seek the free, prior, and informed consent of affected Indigenous communities in the NCAA and meaningfully consult existing Msomera residents affected by the resettlement in line with national and international obligations.

Provide all affected communities access to all relevant information on proposed conservation strategies and developments that would impact their lives as individuals and as a community.

Guarantee the participation of all members of affected communities in decision-making related to land and natural resources, including through inclusive gender- and youth-responsive processes in deciding conservation strategies that respect and protect their rights.

On Education and Health

Uphold the rights of Massai to education, the highest attainable standard of health, to water and sanitation, to adequate housing, food and to take part in cultural life in the NCA.

Restore job openings for government-paid medical staff at medical facilities, including Endulen Hospital and other dispensaries, in the NCA.

On NCAA Rangers

Require and ensure that rangers are appropriately trained in national and international human rights law and standards and subject to effective independent oversight and accountability.

On Monitoring and Grievance Mechanisms

Conduct ongoing monitoring and cease the implementation of conservation strategies that violate rights such as protected areas or conservation-related forced evictions and involuntary displacements.

Set up an independent alternative grievance and redress mechanism that can receive complaints of and provide remedies for human rights violations related to the relocation of residents from the NCA and resettlement in Msomera.

To the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority

Restore funding for services and upkeep of existing infrastructure in the NCA, including to Endulen Hospital and local schools, re-establish and strengthen the Ngorongoro Pastoralist Council, and ensure there are no hurdles for the Pastoral Council to implement its mandate.

Consult with community representatives, including the Pastoral Council to develop clear guidance around construction authorizations, and permitted construction materials, for example, found locally, sourced sustainably, and are culturally significant to the community.

Design an “open door” system, with the involvement of representatives from NCA communities, that eliminates or minimises the burden of paying the entry fee on NCA residents who do not have their identification documents to enter at the gates and provides ease of access to these Indigenous community members.

A map and tourist information at the Loduare gate of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. (Human Rights Watch)

A map and tourist information at the Loduare gate of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. (Human Rights Watch)

Develop a rights-respecting conservation strategy with standard, transparent operating procedures on inclusive consultative processes with NCA communities.

Engage with communities in the NCA to build a plan for sustainable food and water sources that is culturally appropriate, supports their livelihoods, and ensures they are food secure.

Implement long-term community-led monitoring and evaluation, recognising that planned relocations require long-term support and oversight.

Extend timelines for support to families that have been relocated from the NCA and provide compensation based on their informed consent.

Allow relocated residents to return to the NCA, should they wish to do so, and facilitate their return, including through financial assistance to rebuild houses and buy cattle.

Investigate abuses by NCAA rangers in the NCA, including restrictions on movement, and hold them accountable through appropriate disciplinary and judicial avenues.

Methodology

This report is based on research that Human Rights Watch conducted in Tanzania in Dar Es Salaam; Arusha, Endulen village in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Mto Wa Mbu, and Karatu villages in Arusha region; and Msomera village and Handeni town, in Handeni district, Tanga region between August 2022 and December 2023.

Human Rights Watch interviewed nearly 100 people, including 37 women and 57 men, for this report. Interviewees consisted of community members of the NCA who are facing relocation and those who have been relocated to Msomera village, existing residents of Msomera village, a government administrator, representatives of nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), and local activists.

Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in-person and by telephone. In-person interviews consisted of individual interviews and group interviews of between two and four people, except in one meeting with 10 people. The 10-person group interview in Endulen, NCA, was a result of restrictions on movement within the NCA, surveillance by NCAA rangers, fear of discovery, and to minimise exposure of residents and possible government reprisal against local community members who spoke with Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch conducted the interviews in English, Kiswahili, and Maa, with the aid of interpreters as needed.

Interviews took place in confidential settings or remotely through secure means of communication. Human Rights Watch informed all participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, how the information would be used, and that they could refuse to participate or end the interview at any time. Each participant orally consented. Human Rights Watch did not compensate interviewees or offer other incentives for participating.

The report uses pseudonyms and withholds identifying details to protect interviewees from possible reprisals from government authorities.

In addition to interviews, Human Rights Watch reviewed legal documents, including laws, ministerial regulations, court decisions, and other material related to the NCA and land rights in Tanzania. Human Rights Watch also reviewed other secondary sources including NGO reports, research institutes, and media articles.

On May 10, 2024, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ministries of Natural Resources and Tourism, Health, Education, and Community Development, Gender and Children; Offices of the President – Palace (Special Work), and Regional Administration and Local Government; Arusha Regional Office, Ngorongoro District Commissioner, Tanga Regional Office, and Handeni District Commissioner; Tanzania Police Force; and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority (NCAA), to share its research findings and request information but did not receive a response.

Background

Tanzania’s Efforts to Improve its Image

Samia Suluhu Hassan became Tanzania’s first female president on March 19, 2021, succeeding President John Magufuli, who died on March 17, 2021.[1] A marked deterioration in respect for human rights, including government clampdowns on the media, NGOs, political opposition, and other critics of the government had characterised Magufuli’s presidency.[2] Shortly after Suluhu Hassan took office, she promised to address human rights concerns and took steps to remove some restrictions on freedoms of expression and assembly, such as lifting a six-year ban on political rallies by opposition parties, and a ban on four media outlets.[3] However, restrictions on the media and civic spaces, and arbitrary arrests of journalists and government critics, continued.[4]

President Suluhu Hassan has spearheaded a campaign to boost tourism in Tanzania after it stagnated during Magufuli’s presidency and the Covid-19 pandemic.[5] The campaign sought to attract international tourists to Tanzania by promoting its beaches, wildlife, mountains, and cultural heritage. In an installment of the long-running show “The Royal Tour,” which was shown on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States in April 2022,[6] President Suluhu Hassan took filmmakers on tours through Kilimanjaro National Park, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), the Serengeti National Park, and Mkomazi nature reserves, among others.[7]

Maasai’s Indigenous Practices and Conservation

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has set out four key criteria for identifying Indigenous peoples: “the occupation and use of a specific territory; the voluntary perpetuation of cultural distinctiveness; self-identification as a distinct collectivity, as well as recognition by other groups; an experience of subjugation, marginalisation, dispossession, exclusion or discrimination.”[8] The commission stated that “a common thread that runs through all the various criteria that attempts to describe indigenous peoples – that indigenous peoples have an unambiguous relationship to a distinct territory and that all attempts to define the concept recognise the linkages between people, their land, and culture.”[9]

The Maasai are an Indigenous people who,[10] alongside other ethnic groups, have occupied the lands of Ngorongoro in northern Tanzania for generations.[11] They grow maize, beans, pumpkins, and sweet potatoes, and they graze cattle, sheep, and goats, which require large areas of pastureland. Because the Maasai strive to live harmoniously with wildlife, their customs promote conservation of natural resources.[12] Such customs prohibit the consumption of bushmeat – meat from wildlife – instead of beef from their cattle; and that tree branches, not a whole live tree, should be cut for use. Further, the Maasai’s traditional rules on managing pasture areas include fallow periods, grazing timed to season, and wildlife migration patterns.

Over centuries, the Maasai have contributed to the creation of an environment that promotes healthy interactions and mutual adaptation between pastoralists, livestock, and wild animals.[13] Their cultural and spiritual practices, including rituals on adulthood, are interwoven with the land, with sacred areas for assemblies to teach young Maasai about their culture and how they live with the surrounding ecosystem.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area Multiple Land Use Plan

When British colonial authorities declared the Serengeti area a national park in 1951,[14] communities within its borders were relocated to Ngorongoro for permanent settlement. Based on negotiated agreements between the Maasai who previously lived and used the Serengeti, and the colonial government, the government established the Ngorongoro Conservation Area in 1959 to create a permanent homeland for the people who lived in and around the Ngorongoro Crater, the vast majority of whom are Maasai herders.[15] The NCA was created as a multiple land use area, with Maasai traditional pastoralists coexisting with the wildlife.[16]

A United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) World Heritage Site since 1979, the NCA spans about 809,440 hectares that include vast areas of highland plains, savanna, savanna woodlands, forests, and the Ngorongoro Crater.[17] It adjoins the Serengeti National Park and is part of the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem in functioning as wildlife corridors essential to protecting the integrity of animal migrations.

The NCA Authority is a parastatal supervised by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism that manages the NCA.[21] There are 11 wards in the NCA, sub-divided into 25 villages, with 16 having official registration numbers. The villages have been surveyed, boundaries delimited and registered, per the 1982 Local Government (District Authorities) Act,[22] through the Ngorongoro District Council

[23] The commissioner of lands, ministry of lands, housing, and human settlements development, has earmarked 18 villages to survey, map and legalise as village land, per the 1999 Village Land Act.[24] The population of the NCA is estimated at 100,793, according to Tanzania’s 2022 census.[25]

Since it was created, the NCA has integrated conservation with human development.[26] The NCAA’s General Management Plan, created in 1996, has primary objectives to conserve the natural resources of the NCA, protect the interests of Maasai pastoralists, and promote tourism.[27]

Over time, the Tanzanian government, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, which provides authoritative interpretation of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention,[28] and its advisory bodies,[29] the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), and the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), three international organisations named in the Convention, have flagged human and livestock population growth within the NCA as a cause for concern.

[30] These institutions have pointed out that there would be an increased need for land and resources, which would exert heightened pressures on and possibly disrupt the ecosystem.[31] These concerns eventually led to a call by the UNESCO World Heritage Center and its advisory bodies for the government to review the General Management Plan,[32] and a recommendation to “promote and encourage voluntary resettlement of communities, consistent with the policies of the Convention and relevant international norms, from within the property to outside by 2028.”[33]

Human Rights Watch has not made a determination on the validity of the concerns regarding human and livestock increase in the NCA. However, even if these concerns are valid, addressing them cannot be used as a justification for human rights abuses, and that the government should engage with communities in the NCA to devise rights respecting solutions for the preservation of their traditional livelihoods and the NCA.

The government established the Pastoral Council of Ngorongoro Pastoralists (Ngorongoro Pastoral Council) in 1994, and it took effect in 2000.[34] The Pastoral Council, consists of representatives of Village Councils and Ward Development Committees, including ward councillors, village chairpersons, women, young people, and traditional leaders. The Pastoral Council develops and plans for the implementation of projects for the purpose of development of pastoralists within the NCA.

[35] It submits proposed projects to the NCAA, and the NCAA transfers the funds budgeted for development projects in any given financial year to the Pastoral Council to fulfill its function.[36] The Pastoral Council also advises the NCAA Board of Directors regarding development projects in the NCA, such as during the planning and construction of new hotels, and campsites.

The Pastoral Council provided scholarships for schoolchildren and university students, and it constructed primary schools, dams, and boreholes, until the NCAA took steps to defund it starting in 2019.[38]

The Tanzanian government and the NCAA have, since at least 1975,[39] cited concerns over increased human and livestock population within the NCA to justify restricting the access of community members and their cattle to certain areas that the NCAA considers as high priority areas, including the Ngorongoro crater floor, crater rim, and the northern highland forest reserve

[40] They also prohibited farming—phased out over a period of time,[41] and set up separate zones for human settlement and wildlife. Around 2021, the government devised a plan to relocate about 82,000 residents out of the NCA by 2027.[42]

Previous Involuntary Relocation and Evictions of Maasai

Since 2022, the government has implemented plans to resettle Maasai families that live in the NCA to Msomera village, Handeni district, Tanga region, which is about 600 kilometres east of Ngorongoro. Msomera was selected, according to Albert Msendo, Handeni district commissioner, because the area is a “remote wilderness with many areas that had not been interfered with by farming activities, making it easy to plan for pastoralist activities,” adding that other pastoralist Maasai communities had already occupied Msomera.[43]

This is not the first time the government has relocated people from the NCA. Between 2007 and 2010, the NCAA relocated 159 families from the NCA to Jema Village, Sale division, Ngorongoro district

[44] Though the government had established infrastructure for social services including a primary school, a medical dispensary, police post and piped water, the government asserted that the resettlements were not completely successful.[45] More than 50 percent of the resettled residents have since moved back to the NCA or other parts of the country.[46] In 2009, the 50 to 70 families that had remained at the resettlement site had faced resistance from the host communities and had been planning to leave the area as well.[47]

Forced Relocation of Maasai from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area

According to the 2019 Multiple Land Use Model (MLUM Plan) of Ngorongoro Conservation Area report, previous relocations from the NCA were not successful,[51] but the authorities have pressed on with new planned relocations.

On June 16, 2022, the government began relocating the Maasai from the NCA to Msomera village, Tanga region. Government estimates indicate that about 551 households, comprising 3,010 people, and 15,321 livestock, have been relocated as of January 2023.[52] Msendo told Human Rights Watch that contrary to what happened with the relocation to Sale division between 2007 and 2010,[53] the government has made efforts to coordinate with the local authorities from both regions, including the NCAA, Ngorongoro District Council, and Handeni District Council.[54]

However, the government’s planning and implementation process have failed to ensure that the authorities sought free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) from community members. The government plans to relocate thousands of Indigenous Maasai herders from land they have used and occupied for generations should have triggered an FPIC process for the government to seek the affected Indigenous peoples’ free and informed consent before the relocation plan was adopted and prior to its implementation.

The affected Maasai communities were not involved in designing and during the adoption of the plan. Further, the government has not adequately informed and consulted the communities regarding their relocation from the NCA and resettlement in Msomera.

Authorities are also driving Maasai families in the NCA to leave against their will by violating their human rights. They have reduced the availability and accessibility of goods and services essential to residents' human rights by defunding education and healthcare facilities. They have restricted residents' freedom of movement and access to ancestral lands that contain cultural sites and pasture vital for livelihoods.

NCAA rangers have assaulted and harassed NCA residents if they do not comply with the government’s rules, as documented below.[55] As a result, some residents said they had no choice but to leave the NCA. These actions used by authorities to force residents out of the NCA violate a range of NCA residents’ rights, and together amount to forced evictions in violation of Tanzania's treaty obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Inadequate Free, Prior, and Informed Consent Process

Free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) is both a component of the universal right to self-determination and a distinct right of Indigenous peoples consistent with international law and standards. [57] FPIC ensures Indigenous peoples can freely determine their political status and pursue their economic, social, and cultural development. [58] It allows Indigenous peoples to give or withhold consent to a project that may affect them or their territories.

Once they have given their consent, they can withdraw it at any stage. Furthermore, FPIC enables Indigenous peoples to negotiate the conditions under which a development that affects the lands, territories, and resources that they customarily own, occupy, or otherwise use will be designed, implemented, monitored, and evaluated. FPIC centres on meaningful consultation through Indigenous peoples’ own representative institutions or structures (without coercion, intimidation, or manipulation); far enough in advance of any authorization or commencement of activities; and access to all information regarding the activity, policy, or project that would impact Indigenous peoples and their lands.

[59] No relocation of Indigenous peoples from their land or territories should take place without their free, prior, and informed consent and only after agreement on just and fair compensation and, where possible, the option of return. [60]

Human Rights Watch’s research and analysis found that the Tanzanian government has not engaged in any of these processes to ensure the free, prior, and informed consent of the Maasai in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area.

Inadequate Consultation

Building on elements of FPIC, the consultation process, timeline, and decision-making structure should be self-directed by the affected community. That means meetings and decisions take place at locations and times and in languages and formats determined by the affected community; all community members are free to participate regardless of gender, age, or standing; and the affected community must be able to participate through their own freely chosen representatives, while ensuring the participation of youth, women, the elderly, and persons with disabilities as much as possible. [61]

The government did not consult affected communities prior to designing the relocation plan, which is counter to an FPIC process. In 2018, the government reviewed the NCA’s Multiple Land Use Plan and recommended zoning, dividing areas based on allowable activities, such as residential, pasture, and others, with an option for relocation. [63] NCA residents, including community leaders, told Human Rights Watch that the government did not properly consult the affected communities during and after the review.

After the government published its review in a 2019 report, residents and NGOs working with the communities within the NCA issued a community report in May 2022 countering some of the main findings of the government’s report and submitted it to the government. [64] However, community leaders and residents said the government has refused to engage with their report and its recommendations proposing alternatives to relocation. [65]

Residents said that the government decided about “voluntary relocation,” where people would be relocated, and built houses without any input from affected communities or their leaders. A village councillor from Ngorongoro district raised concerns about the lack of transparency: “the government went in secret and identified Msomera and built more than 100 houses in secret.” [66]

Prime Minister Kassim Majaliwa met with community leaders, including village councillors, on February 17, 2022, seemingly to socialise the plan to relocate residents from the NCA. A village councillor who attended the meeting said attendees thought the meeting was meant to hear their views, and they presented several alternate options for relocation, but that the prime minister only came to give instructions on how to register for relocation. [67]

Another community leader, a member of the Pastoral Council, said that any supposed consultation by the government with the community, including the meeting with the prime minister, lacked sufficient engagement of leaders and the communities as a whole.[69]

Inadequate access to information

Regarding the nature of the consultative process, in order for the conditions of FPIC to be met, authorities need to ensure the affected community members have adequate access to information.

This should mean that the affected community should be provided, on an ongoing basis, with information that is accessible (including delivered in a local language, in places they can easily access, and in a culturally appropriate format), clear, consistent, accurate, objective, complete, and transparent.

[74] The Tanzanian authorities, however, provided far too little information on certain aspects of the relocation process, including compensation and what conditions to expect in Msomera. Residents said there are no opportunities to get answers to questions they have related to the relocation process.

Several residents said that the only information they received from the government was from the prime minister during the February 17, 2022, meeting on registering for relocation. The prime minister said that interested individuals should register their names at the offices of the regional and district commissioners and the Ngorongoro Conservation Commissioner.

The chairperson of a village council, the administrative body responsible for governing villages, in the NCA, said:

We have been holding meetings to complain about the government or political party, but there have been no answers since March 2022. We haven’t seen any leader from the district or national level come to these Ngorongoro areas to talk to the citizens and answer their questions since the unrest in neighbouring Loliondo in June 2022].[75] From the district to the national level, no leader has come to listen to the citizens of the Ngorongoro area and know what their problems are. We’ve been shouting, and it’s like the leaders have isolated us. People are losing hope, and they feel like keeping quiet is the only option. [76]

Some residents recounted information they widely believed to be rumours about resettled residents receiving cash compensation of 10 million shillings (US$3,970). Human Rights Watch found that authorities have not released information on compensation, including amounts or how compensation is calculated or negotiated. “The entire process is not open and transparent,” a village council chairperson said. “The government says they are giving money, but no one knows what the government will give them until they have moved. There’s no chance for negotiation.” [77]

Several community leaders said they did not know which villagers registered for relocation until the day they were transported out of the NCA. As such, their community leaders cannot provide them with any support during the relocation process. [78]

A councillor said there is a lack of information regarding the relocation process: “The government has never taken any leaders or representatives to Msomera. The government does not want us to know. If someone registers to move, they stop talking to leaders.”[79]

Given the communities’ inadequate access to information, the opaque relocation process, and no clear pathway for addressing grievances, residents said they have limited avenues to engage with the government to ensure it protects their rights, including whether they choose to relocate or remain.

A youth leader said, We do not know anything about Msomera. What we have heard is that people have lost their livestock. How do we make sure the government guarantees that in two to five years, if resettled residents lose all their livestock, they will get it replaced, receive compensation, or receive support? How can the community make sure the government provides these assurances if we have no information?[80]

Human Rights Watch’s documentation of inadequate consultation and inadequate access to information would also appear to amount to forced evictions as outlined by the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CESCR) and guidelines from the UN special rapporteur on adequate housing.[81]

Funding cuts to social services in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area

All the more than 70 NCA residents who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they did not want to relocate. They said that since 2019, after the publication of the government’s report [82], the government has begun to systematically downsize essential social services for NCA residents and defund the Ngorongoro Pastoral Council. [83] Service provision in the NCA was already less available and accessible and of generally poorer quality than in other areas across the country.[84]

Residents alleged that the government cut funding for public services to force them to leave the area. “In Ngorongoro, the government gave it the name ‘voluntary relocation,’ but there is no voluntary relocation,” one resident said. “The government is using different ways to torture our community.” [85]

The government has reduced the availability, accessibility, and quality of important social services like schools and hospitals in the NCA, including through budget cuts and other limitations on necessary resources such as trained personnel. These practices have undermined the realisation of NCA residents' rights, including to education and health care, and have made their continued access to their ancestral lands far more difficult. Maasai families have been left with no better option than to register for relocation from the NCA to Msomera.

Their registration is not effective consent, as consent in FPIC refers to the collective decision made by the affected Indigenous peoples and reached through their customary decision-making processes. Consent should be sought, granted, or withheld from the affected Indigenous peoples’ unique formal or informal representative decision-making structures.

Defunding the Ngorongoro Pastoral Council

Some of the residents who were or are still members of the Pastoral Council said that until 2019, the council identified community needs, including education, health, water, and food; developed and presented projects to meet these needs to the NCAA board for approval and disbursement of funds; and carried them out. Before the 2019/2020 fiscal year, which started on July 1, 2019, the annual budget of the Pastoral Council was about three billion shillings (US$1,150,000) for development projects and the NCAA student scholarship program. [86] All of the Pastoral Council’s budget came from allocations from the NCAA.

Residents said that in 2019, the NCAA raised allegations of mismanagement of funds by the Pastoral Council with the Prevention and Combating of Corruption Bureau, a quasi-judicial body that investigates and prosecutes corruption offences in mainland Tanzania. [87] According to a Pastoral Council member, these allegations were never proven, but the bureau made a recommendation to the then-vice president and now current president that the NCAA allocate future funds to the Department of Community Development under the Ngorongoro District Council rather than to the Pastoral Council for project implementation. [88]

Pastoral Council members said that the government did not de-register the council but eliminated its yearly budget allocations, effectively ensuring that the council no longer had the ability to implement programmes and make independent decisions. [89] One member described the effect of the government’s decision on the council:

Now, the Pastoral Council has no autonomy; it sits at the request of the NCAA. The NCAA calls the meetings and proposes the budget. The pastoral council's mandate has shrunk. Taking away resources ensures that the Pastoral Council is weak, especially since it has found it impossible to fundraise on its own given that it is considered a government establishment.[90]

Since 2020, the Pastoral Council has not received any money from the NCAA or the Department of Community Development, including money for renovations, construction of school facilities, and other community projects within the NCA, which has adversely impacted the maintenance of school facilities, including the construction of latrines, the repair of classrooms, and the provision of additional desks and beds for the students. [91] Pastoral Council members also said subsequent NCAA funding allocations since then, especially disbursements for health centres and schools, were reduced.

Impact on Access to Education

The actions taken by government authorities to intentionally downscale and undermine school conditions in the NCA affected hundreds of children’s access to and enjoyment of the right to education.

Limited Disbursement of Scholarships

The Pastoral Council’s defunding, according to interviewees, has led to delays in the disbursement of funds to university students, creating cost barriers that reduce access to higher education. Since 2020, the NCAA has shifted the responsibility of sponsoring students on scholarship from the Pastoral Council to the Ngorongoro district office. [92] These scholarships are for university students from the NCA and are financed by the NCAA through the Student Scholarship Program. [93]

University students who benefit from school-related support or sponsorship said that in the past, the Pastoral Council had usually promptly disbursed their funds. However, university students said they now experience long wait times and serious challenges before receiving the funds. “Sometimes the money comes from the district council after a long time, and usually after a lot of struggles,” one student said. “Plus, it’s not enough.” [94]

An NCA resident said that university students have not only received less sponsorship support, the district council delays scholarship payments, and in some cases, the university does not recognise them as scholarship beneficiaries as they no longer receive introductory letters from the NPC. [95]

Impact on the Availability of Adequate School Facilities

Community leaders and school administrators are required to apply for funding and authorization from the NCAA to construct or renovate school facilities within the NCA. However, since 2021, the NCAA has refused all requests for construction permits without providing any explanation. [96] Community leaders said if they attempt to use their own resources without NCAA permits, they face harassment and even arrest.

Human Rights Watch learned of several schools in the NCA in poor condition as a result of the NCAA’s refusal to release funds or issue permits for improvements to primary and secondary schools.

Residents highlighted instances when this happened. [97] Esere Primary School in Esere has many old and dilapidated buildings, overflowing latrines, and an inadequate number of classroom desks, but community members said the NCAA has rejected their requests for funding and permission to renovate. [98] Olbalbal Primary School in Olbalbal needs a latrine, but the NCAA rejected a proposal to construct one.

[99] The Ngorongoro Girls Secondary School, which has about 500 students, has an inadequate number of desks, so children sit on the floor during classes, and there are only seven latrines in one building for all the girls. The NCAA appears to have been stalling to authorise the construction of another building for latrines. [100] And when the roof of a building in Misigiyo Primary School was destroyed during the rainy season in 2021, the NCAA transferred 2,780,000 shillings ($1,065) to the school account to rebuild when the incident happened in 2021.

However, since then, the NCAA has refused to issue a permit to carry out the renovations and has refused to allow community residents to bring new iron sheets into the NCA to repair them. Community members said that when they attempted to reuse parts that came off the roof when it was damaged, the NCAA refused to issue a construction permit.[101]

Buildings in Mokilal Primary School, Mokilal village, Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. (2023 Human Rights Watch)

Buildings in Mokilal Primary School, Mokilal village, Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. (2023 Human Rights Watch)

Permits are key, without which residents cannot enter the NCA gates with the necessary construction materials for school facilities, such as metal sheets for roofing, or make improvements themselves without a permit.

When the community raised funds to renovate and construct school buildings in the NCA, the NCAA denied residents the required permits as well as authorization to transport construction materials into the area. It does not provide explanations for its rejections. For example, Ngorongoro Girls School has 300 million shillings ($115,000), which was raised over several years by the community, to renovate the school, but the NCAA has not issued the required permits.[102]

In 2022, one resident used her own resources to build two classrooms for a preschool, but the NCAA did not allow her to bring roofing materials into the NCA. Consequently, the students lack coverage from the rain during the rainy season. [103]

Residents have attempted to use traditional materials to construct, but that presents its own challenge due to restrictions on cutting trees and branches.

In 2022, the government redirected educational funding from the NCA to the Tanga region for new schools in Msomera, which is where NCA residents are being relocated.[104] According to media reports, the Ngorongoro district council issued two directives to six public schools in the NCA in March 2022, instructing them to redirect approximately 200 million shillings ($76,500) in COVID relief funds to the Msomera resettlement site. [105]

Defunding and downgrading health facilities

Residents whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said the government has, directly and indirectly, caused a reduction of available health services and reduced the quality of health services in the NCA.

A councillor in Esere village provided examples of how the government has ceased supporting health care in the NCA:

I can’t compare Endulen [the hospital] now to before. Before, the government provided support, plus hospital staff, which they paid. Before, Endulen had a mother and childcare services with enough medicines. Now, the government has cut off all support; they have taken the doctors they brought [to Endulen Hospital] back into government hospitals. [106]

In October 2022, the government announced that it would downgrade Endulen Hospital, a 110-bed hospital managed by the Catholic Church since 1965 and the only hospital providing comprehensive medical services to Maasai living in the NCA, to a dispensary due to staffing limitations.[107] A medical worker described how the government arrived at this decision: “In 2018, the NCAA cut off funds to Endulen Hospital.

It usually allots about 30 million shillings ($11,900) annually. But Endulen Hospital had project funds from other donors until 2022.” [108] The medical worker said the hospital’s other donors have since suspended funding because they are worried about its sustainability due to uncertainty related to the relocation process and the possibility of the hospital being forced to shut down.[109]

By 2022, the number of hospital staff had reduced from approximately 60 to 17 people as government-paid staff left to take up government jobs advertised in other locations, and no new openings were advertised at Endulen Hospital to replace the staff that left. In the past, vacancy announcements at Endulen Hospital were advertised for government staff. In December 2022, the government established a committee led by the regional medical officer and the district medical officer to investigate the services at the hospital and found that it has a limited staff.

The body thereafter recommended that the hospital discontinue some of the services, including ambulance and emergency services, as a result of inadequate staffing, a downgrade from a hospital to a clinic, and permitting the provision of basic primary care and pharmacy services only. [110]

Residents and two medical staff said that Endulen Hospital has experienced a serious shortage of medicines, claiming that as a result of such a shortage, pain-relieving and fever-reducing tablets were being doled out for every ailment.

Residents told Human Rights Watch that, as a result of a lack of some previously available medical services, they had to seek treatment at less-equipped dispensaries. A medical worker at a dispensary in the NCA explained that their four-room dispensary witnessed an increase in the number of patients over the last year: “When patients see that many services are available here, they talk to each other, so many more come to us.”

[111] He pointed out that this dispensary is too small to treat all the patients who formerly accessed health care at Endulen Hospital and that it cannot expand because the NCAA has denied its request for a construction permit. He added that the staff also feared the government would shut down the dispensary due to the relocation. [112]

Furthermore, some of the other options for medical services in the area have been interrupted. In February 2022, the government grounded Flying Medical Services, a medical outreach service provided by the Arusha Catholic archdiocese that provided clinics across Ngorongoro district, which particularly benefited pregnant women, especially those experiencing difficult childbirth, because it could quickly evacuate patients to other hospitals outside the NCA. [113]

To access important services, residents have been forced to travel far distances outside the NCA. An activist recounted the distances people needed to travel to get certain medicines:

The government used to supply medicine for HIV treatment, but they’re no longer doing that. If you want to get the medicine for that, you have to go [60 kilometres] to Karatu [in the neighbouring Karatu district]. And for TB treatment, they stopped doing that as well. You have to go [200 kilometres] to Arusha [the regional headquarters] to get that. [114]

Increased distance to primary healthcare facilities poses serious challenges in situations where transportation choices are limited and reliance on non-motorised modes of transportation, including walking, is predominant.

[115] A community worker said that a pregnant and anaemic woman could not get a blood transfusion at Endulen Hospital due to the reduction in staff and services, and as a result, she was referred to a hospital in Karatu, about 60 kilometres away. [116] Another pregnant woman from Esere, who was hit by a safari vehicle, had to be rushed to Karatu for medical treatment; on her way back into the NCA, she went into labour and gave birth in the car.

An entryway at Endulen Hospital in Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. © 2023 Mathias Rittgerott/Rainforest Rescue

An entryway at Endulen Hospital in Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA), Arusha region, Tanzania, on June 22, 2023. © 2023 Mathias Rittgerott/Rainforest Rescue

[117] Given the poor quality of health care in the NCA, medical workers advise pregnant women to go to Karatu for pregnancy and prenatal care; some with difficult pregnancies have had to stay in Karatu, away from their families, for weeks while waiting for labour to start.

In some crisis and emergency situations, the outcomes have been dire. One woman said that between April and May 2023, three women died as a result of pregnancy-related complications for which they could not get the necessary, life-saving health services at Endulen Hospital. [118] Another woman shared a health-related difficulty within her family: “My uncle’s daughter gave birth to twins. The babies were born on the way to Karatu Hospital. They were early, at seven months. Both babies died because we could not get them the right services as soon as possible.”[119] Human Rights Watch did not conduct an analysis of pre- and post-2022 maternal and infant mortality rates in the NCA.

Residents said that in the past, the government and NGOs had carried out campaigns to raise awareness of pregnant women’s and newborns’s health and encouraged women to go to the hospital during pregnancy and for antenatal and postnatal care. Given the current situation, residents expressed their concerns that the government is reversing its own policies by reducing access to health care in the NCA. “We have been educated that we should go to the hospital when pregnant,” one woman said. “But now we don’t have those services anymore.”

World Health Organisation data analysed by Human Rights Watch revealed that the government of Tanzania spent the equivalent of only about 0.91 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) or 5.14 percent of its national budget on health care in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available. [120] This falls far short of two key international benchmarks associated with reducing inequalities in healthcare access and outcomes: spending 5 percent of GDP or 15 percent of national expenditures on healthcare through public means.

This level of public investment also fails to meet Tanzania's explicit commitment in the African Union’s 2001 Abuja Declaration to spend at least 15 percent of its national budget on health care. [121] While Tanzania has also faced significant public debt issues, paying roughly four-times as much on a per-person basis to service its external public debts in 2021 than it paid on health care, the government needs to take efforts to ensure that socially and economically marginalised groups, including Indigenous communities, do not bear the brunt of any funding reductions.

Restrictions on movement in and out of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area

Some residents told Human Rights Watch that the NCAA had restricted entry into the NCA since February 2022 [122], limiting the movement of residents, including those who needed to access services outside the area.

NCAA rangers require residents to show identification (ID) as proof of residence within the NCA before allowing them passage through the gates to their villages. Residents who do not have ID or voter registration cards or forgot them at home are denied entry when returning home and must pay 11,800 shillings ($5), the fee for entry as a Tanzanian tourist. “The people in NCA come out and go to Karatu to buy grain, to the hospital, or to a student going to university,” one resident said.

“When they return, the gatekeepers deny them entry, embarrassing them.” [123] A ward councillor said she was refused entry when returning from a councillors’ meeting in Loliondo because she forgot her voter registration card at home. She stayed at the gates until someone came along who could identify her. She said, “If I can face that, how are normal people faring?” [124]

One NCA resident said that NCAA rangers would arbitrarily ask for different forms of identification:

If today I am in Arusha and I want to go to Ngorongoro, I must have an ID to enter the place. Even if they know you’re a resident, you must show that. You can have a national ID, but sometimes they want you to show them the electoral card. And sometimes you have the electoral card, and they want you to show them the [national] ID.[125]

The NCAA also charges all vehicles, including local transport vehicles, a permit fee for every entry. The fee differs based on the weight of the vehicle, with a minimum of 23,600 shillings ($9). Drivers pay a per-day fee. Residents say the drivers of vehicles transporting people in or out of the NCA have transferred these extra costs to residents, making transportation far more expensive and “going out difficult.” [126]

A traditional leader explained the repercussions for residents who fall sick and cannot afford the cost of travelling:

Every resident is feeling the pain. If you fall sick, you think of the huge cost you will incur to search for health services. The poorer people are much more vulnerable because they don’t have money to travel far, and the local dispensaries do not have medicines. You can sell livestock and access these services. The other option is to use local traditional herbs or pray to God for a miracle. [127]

A resident who has been publicly critical of the government’s relocation of Maasai people from the NCA said authorities had blocked him from returning home because of his activism. He said that a police officer denied them entry at the gate to the NCA when they returned home from a trip in October 2022, saying that their identity document was not registered. The activist believes they were followed by government security officers during their trip and that the officers at the gate had been forewarned about their arrival.[128]

The NCAA requests differing IDs to prove residence, and otherwise charging a tourist fee for residents to return home places a huge burden on Indigenous peoples who have historical and current traditional ties to the land and whom the government has enclosed in the NCA. The NCAA needs to design an “open door” system, with the involvement of these communities, that minimises or eliminates this burden and provides ease of access to Indigenous community members.

Restrictions on access to pasture, water, and cultural sites in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area

As a result of government laws and policies, the Maasai communities in the NCA have limited access and use rights over the land they have lived on for generations and no control over or ability to make decisions on the land, including how revenue from tourism is shared. [129] This includes their access to longstanding pastures, water sources, and cultural sites.

Access to Pasture

NCA residents said that the authorities have restricted their access to important grazing areas, which has been challenging as they depend primarily on animal farming for their livelihood. They said the authorities have blocked them from grazing their animals in different parts of the NCA, including the crater, denying their animals vital water sources, grass, and nutrient-rich volcanic rocks and soils. In addition, residents said the NCAA stopped providing veterinary services for community members’ livestock around the time the government began relocating people to Msomera. [130]

One village chairperson said: The government is starting to make us not function at all. They try to weaken us in all means of life. To despair, not to fight, give up, and move out. They are trying to make sure that pastoralism comes to an end. We never chase the wild animals to move out. We are very good conservators; we don’t hate the wildlife.[131]

Some residents said that around 2016, government officials informed community members in the NCA, through their leaders, of a decision prohibiting their livestock from accessing the Ngorongoro Crater because of conservation and “ecotourism.” This was disruptive since wildlife and livestock in the NCA rely on geophagy—eating earth, which is done by a wide variety of animals and humans—for nutrient supplementation and to alleviate gastro-intestinal disorders.

The Ngorongoro Crater contains precious perennial water sources, which were invaluable during the dry seasons, and earth licks, which were key for supplementing livestock with nutrients, particularly micronutrients that might be deficient in the grass growing in the area. [132] In turn, these nutrients and the availability of water are beneficial for livestock health and boost cow milk production, with important nutritional and financial benefits to the local human population.

Residents had historically grazed their animals in the crater because it contributed to the health and milk production of their cattle, since there are high deposits of sodium and micronutrients such as selenium, cobalt, manganese, and molybdenum.

[133] Three residents of Alaitolei and Nainokanoka wards said that when the NCAA prohibited access to the crater, the authority said they would provide water for human and livestock use in all the villages and supply supplemental salt to ensure the cattle could get salt at home and not by geophagy in the crater. [134] “The [NCAA] was going to start a ranch at Ngairish sub-village of Kakesio ward,” said one of the residents. “We were going to learn how to grow grass that is good for cows. We will have a good breed of cows to increase the numbers. We said this was a good plan.” [135]

Residents said that since 2017, when the government began providing supplemental salt to their communities, up to 77,000 cattle had died by December 2021. [136] Community members said they believed that the salt supplied by the government was poisonous and unsafe.

Their suspicions were confirmed by a mineral analysis of a salt sample by the Tanzania Veterinary Laboratory Agency, a government agency, which concluded that the salt did not comply with the Grazing-Land and Animal Feed Resources (Standard of Animal Feed Resources) Regulations of 2012. [137]

A village council chairperson said the tainted salt affected his community: We lost all our cattle. In my village, 6,294 cattle died. I lost 120 cattle. [One person] was arrested on June 30, 2022, Simon Saitoti, the ward councillor, because he spoke out about the salt. He was charged with murder [of a policeman in Loliondo]. His cattle all died. He went into prison as a rich man and came out as a poor man.

[138] In addition to restricting access to the Ngorongoro Crater, NCAA rangers have blocked livestock from accessing water in other areas, including the northern forest, Marshes, Ndutu, and Ormoti and Embakaai craters. [139] Residents allege that NCAA rangers beat and arrested community members for grazing their animals in areas where the NCAA has prohibited the community from accessing them.

On June 13, 2022, security forces arrested Paresoi Kiboko after he took his livestock to graze in Ndutu, an area in the NCA that the community had accessed for several years. [140] A lawyer familiar with Kiboko’s case said that rangers beat and detained him and took him to court the next day, where he was charged with grazing in a prohibited area and threatening the rangers with a spear.

[141] Because Kiboko did not speak English or Swahili and the court did not provide an interpreter, he could not follow the court proceedings in the case against him. Kiboko was imprisoned for nine months before being released in March 2023.

Access to Water Points

The government’s 2016 restrictions on the communities’ access to certain areas within the NCA included places with invaluable water sources for villagers and their cattle.

One community leader told Human Rights Watch:

In my village, we used to have a lot of potential places [to access water for our livestock]. There are certain places we would not go to at certain times of the year; say, from December to May, we wouldn’t go there because of wildebeest [fearing the transfer of disease that affects cows]. We would go to the highland and leave the land for the wildebeest. And at certain times of the year, there are areas we would only go to during times of drought. But now they’re starting to tell us you cannot go there—places like Ndutu. The NCAA is starting to beat cattle herders.[142]

Residents said the NCAA assured them that their communities would have access to other water sources outside the crater. However, this has not been the case, as our research showed. “The NCAA has not made a permanent place to access water [for livestock],” one woman said. “Last year [2022], during the drought, many of our animals suffered.” [143] Another resident noted that although the British colonial government had dug more than 10 water dams to collect rainwater, only two remained functional.

Since almost all the cattle in the neighbouring villages use those two dams, there is a lot of pressure on the dams. They cannot sufficiently water all the animals because the water in the dams is inadequate, and the pressure from a large number of animals relying on them means the cattle could damage the dams.

Several residents said the NCAA had not renovated the eight non-functioning dams or constructed new ones. [144] One woman said that although the NCAA has provided pipe-borne water to communities, it is not effective at maintaining or repairing these water points.

“When there is destruction, the NCAA refuses to repair,” she said. “When we got the parts to do the repairs, the NCAA refused [and said] that we shouldn’t repair it and that they have an expert outside the NCA that will repair it.”[145]

The NCAA’s restrictions on key pasture and water points have negatively affected the health of livestock, production of milk, and income from sales of milk and cattle. The NCAA also imposed a complete ban on crop cultivation, which was first introduced in 1975 to support biodiversity conservation.

[146] In the past, the prime minister has temporarily waived the ban, such as in 1992. [147] Residents acknowledged that the NCAA provides maize at a subsidised price, but since the confirmation that the death of their cattle was due to the NCAA’s tainted salt, discussed above, residents have lost trust in the NCAA, and some have refused to purchase the maize.

[148] At the time of our interviews in June 2023, it had been almost two years since some residents stopped buying subsidised maize. The restriction on pasture and water points and the ban on cultivation have led to food insecurity and health implications for the communities within the NCA. [149]

Access to Cultural Sites

In addition to restricting their access to necessary sustenance for their livestock, residents said the authorities have blocked their access to important cultural and traditional sites since around 2016. According to one traditional leader, they are not allowed in ritual sites at the Ngorongoro Crater, the Olmoti Crater, and Mbakai, and Maasai get arrested for going there.[150]

The denial of access to cultural sites and the prospect of relocation could result in a disconnect for the Maasai from their culture and way of life—violating their right to culture. This is because their identity and culture are woven into their land. An elder in Endulen who witnessed the 1959 colonial-era relocation of Maasai from the Serengeti recounted the loss of permanent lands:

Serengeti was used for grazing and temporary settlements, and we moved to the highlands [Ngorongoro] during the dry season, where we buried our ancestors. We don’t have anywhere else. Before, our people might have given up Serengeti because we had the highlands, our permanent area. Now, we don’t. [151]

The NCAA’s restrictions have occurred over decades, with promises to provide supplemental grain, access to water points, salt, ranches, and veterinary services for livestock to mitigate harm to the affected communities and their livelihoods, which it is not currently fulfilling. Under the UNDRIP, consent is not a one-off decision but part of an ongoing FPIC process that is sought, given, and can be withdrawn. Human Rights Watch concluded that the NCAA’s promises of supplemental goods and services have been eroded since the relocation plans were announced, and the restrictions on the communities’ access to pasture, water sources, and cultural sites do not meet an FPIC standard.

Abuses by Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority Rangers

The NCAA employs rangers to guard entry points and other areas in the NCA.[152] In the past, rangers were mostly residents of the NCA or Maasai, but residents said that in recent years, community members whom the NCAA employed as rangers who may have been sympathetic to the communities have been relocated to Msomera. According to one activist:

The people working with the NCAA have their own issues. Because they’re natives [of the NCA], the government is forcing them to relocate. If you don’t want to relocate, they will terminate your employment. My uncle works with the NCAA, and they were all pressured. They have to agree with the government.[153]

Some NCA employees who chose not to relocate to Msomera were instead transferred to the Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority and to other protected areas outside of the NCA, including the Loliondo Game Controlled Area in the Loliondo division. [154]

NCA residents described how the relationship between NCAA rangers and community members has deteriorated dramatically since the government began implementing the relocation programme in 2022. They also said that rangers have attacked and beat people living in the area. Human Rights Watch documented at least 13 incidents of alleged beatings by NCAA rangers between September 2022 and July 2023. Residents said these abuses escalated around September 2022.

[155] One NCA resident described how NCAA rangers beat his 35-year-old friend in September 2022 on his way to his uncle’s funeral in Nainokanoka ward:

He was just walking, and they just punished him. They made him kneel—kichura [toad style]—and they punished him using a stick. He got injuries to his legs. We don’t have anything to report. You go to the same police who have beaten the guy, so you can’t get any aid. There are many cases like this. Rangers are like people who are above the law. [156]

That same month, two rangers severely beat another resident, Letee Ormunderei, at his home in Ngoile ward in the NCA, breaking his legs. An activist said one of the rangers told Ormunderei, “We want you to go to Msomera.” This attack allegedly occurred because Ormunderei owned a motorcycle, which residents of the NCA are prohibited from owning inside the national park.[157]

Human Rights Watch also learned of a ranger attack against a child that has gone unaddressed. On July 13, 2023, an NCAA ranger allegedly beat 15-year-old Joshua Oleparoto, breaking his teeth with the butt of his rifle, as he grazed cattle in the Ormoti area, where residents are prohibited from grazing animals.[158] According to a lawyer familiar with the case, Oleparoto reported and identified the ranger to the police, but at the time of writing, the police had not followed up with Oleparoto or charged the ranger with any offence.

Several women said that before the relocation started, women could construct small houses for themselves, especially as additional wives joined their marriage, but now they were not allowed to build such additional homes. One woman said:

If you try to build a small house as a woman, the rangers will take you to the police. The police will order you to pay a fine. The fine is not a fixed amount; it is not uniform, and sometimes they take you to court.

[159] Another woman explained, “In the past, we used to cut trees to build our houses without any problems. But now, if a house collapses and you are seen cutting trees, you are followed until caught and arrested.”[160]

Other residents said NCAA rangers began harassing women and girls for picking up dead tree limbs for firewood. “Women collecting firewood are detained; their machetes are confiscated,” an elder in Endulen said. “Now the rangers are restricting everything, including getting poles to corral our livestock and protect them from wild animals.” [161] During Human Rights Watch’s visit to the NCA in June 2023, girls who were out collecting fallen branches for firewood were cautioned to be careful and watchful, so they were not intercepted by rangers and had their machetes seized.

Challenges Around Relocations to Msomera Village

Our grandfathers left Serengeti for conservation. Our fathers lived inside the [Ngorongoro] crater, and they were removed from there. We are tired of moving. We worry that if they move us to Msomera, they will even come to move us from there. We want to have a stable life. [165] Simon M., Councillor, Mto wa Mbu, June 21, 2023

The Tanzanian government’s resettlement plan consists of relocating Indigenous Maasai people from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area eastwards, about 600 kilometres, to Msomera village in Handeni district, Tanga region. The resettlement has been carried out without an FPIC process, and there is inadequate consultation and information sharing with residents of either community. There are 91 villages in Handeni district, of which Msomera is the only one historically occupied by herder communities, including Maasai people. [166] As of 2022, it had a reported population of about 200 households and 7,000 people. [167]

The government estimates that as of January 2023, more than 500 households, including over 3,000 people and 15,300 cattle, had been relocated from the NCA to Msomera village.[168] Human Rights Watch found that their relocation has many implications, including for their ability to maintain close ties with their families and friends who chose to remain.

The government is heavily invested in the relocation and has provided relocated households with a house and land to farm. It provides other benefits as well. A government official and some resettled residents in Msomera who spoke to Human Rights Watch said for each household the government provided resettlement assistance, including transportation, cash of about 10 to 19 million shillings ($3,964 to $7,532), about 200 kilogrammes of maize, 5 to 7 acres of farm and residential land, and a house in Msomera.

[169] However, the resettled residents said the houses were small, culturally inappropriate, and inadequate for large multi-household families. They said that most or all the cattle they brought with them from NCA have died, likely as a result of water scarcity during the dry season, as they have had to water their cattle with salty groundwater.

The earth roads the authorities constructed in the area were being maintained when Human Rights Watch visited Msomera in June 2023. They had also constructed new infrastructure, including a school, dispensary, post office, police post, water supply system, electricity, and cellular network to service the area while renovating older ones. [170]

Despite these investments, Human Rights Watch found the relocation to have been problematic, including because resettled people were not adequately consulted and that existing Msomera residents were being forced out of Msomera. Former NCA residents have not received adequate government support to relocate to Msomera, as detailed below.

Existing residents of Msomera