How Kenyan girls are trafficked to Russia to assemble war drones

Recruitment was carried out online, particularly via social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, Telegram, and X (formerly Twitter), and through local intermediaries. Paid influencers played a major role in promoting the programme.

For dozens of Kenyan girls, the journey to Russia began with a promise of a well-paying job, a fresh start, and the chance to uplift their families out of poverty, but ended in a nightmare.

Lured by traffickers posing as legitimate recruiters, these young women now find themselves trapped in a foreign country, forced into illegal work under constant surveillance, and at risk of becoming collateral in the Russia–Ukraine war.

More To Read

- Coastal counties face surge in online job scams, officials warn

- IOM launches global campaign to support human trafficking survivors

- Jacob Zuma's daughter Duduzile under probe for alleged recruitment of fighters for Russia

- Court awards Sh5 million to Kenyan trafficked to Myanmar for online fraud

- Interpol flags online advertisements offering costly crossings into Europe

- Kenya’s criminal gangs trace back to independence era, NCIC says

A new report has uncovered how a growing network of transnational traffickers, enabled by systemic failings, allowed more than 400 Kenyan women to apply for passports under a dubious programme. By December 2024, only 14 were confirmed to be working in Russia, and just two had managed to return home.

According to the report, The Migrant Women Exploited for Russia's War Economy by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GI-TOC), the women were recruited to work in what is commonly referred to as the Alabuga Special Economic Zone (SEZ)—a vast industrial complex in Russia’s Tatarstan region that plays a critical role in the country’s war economy. Most of them were unaware they would be building military drones used in the conflict.

The programme offered seemingly attractive salaries with minimal entry requirements. However, the SEZ is where thousands of attack and reconnaissance drones are manufactured for use by the Russian military.

Others were enticed by promises of scholarships or work-study opportunities at Alabuga Polytech, where they were told they would receive vocational training and Russian language lessons, only to discover the true nature of their roles after arrival.

Misleading entry requirements

To qualify, participants needed a high school education, a valid passport, knowledge of 100 basic Russian words (including factory-related terms), and to complete what resembled a business aptitude test in the form of a simulation game.

“The objective of Alabuga Start is to support drone production within the SEZ, though recruits are not told what the zone manufactures until after arrival,” the report says.

Recruitment was carried out online, particularly via social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, Telegram, and X (formerly Twitter), and through local intermediaries. Paid influencers played a major role in promoting the programme.

According to GI-TOC, some recruits were placed in support roles such as cleaning and catering, while most worked directly on drone production lines.

The organisation set out to determine whether Alabuga Start constitutes human trafficking, given the reportedly fraudulent recruitment practices, repressive working conditions, and deception involved.

The findings suggest the programme recruited participants via three main channels: social media, local intermediaries, and diplomatic ties.

"Besides social media, information about Alabuga was also disseminated via Russian-linked media targeting African audiences and repeated by local outlets, often using identical phrasing to official Alabuga materials,” the report notes.

Exploitation and coercion

Testimonies suggest the SEZ exploits underage students and migrant workers. Many were allegedly misled about the nature of the job, the working conditions, and the educational opportunities on offer.

According to Ugandan MP Edson Rugumayo, who served as chair of the Uganda National Youth Council and visited the facility in 2024, around 60 women had travelled from Uganda out of 500 selected recruits. Although the MP was reportedly involved in promoting Alabuga in Uganda, he denied media allegations of labour exploitation at the plant.

Alabuga recruiters had also contacted a secondary school teacher and members of youth organisations to reach more candidates.

In Tanzania, the BDADI (Brighter Dreams and Dignity) Foundation, led by Sharifu B. Dadi, organised a recruitment event in Dar es Salaam. The organisation is described as having a formal partnership with Alabuga Start.

A similar event was held at Norbert Zongo University in Koudougou, Burkina Faso, in June 2023. Images from Alabuga Start’s Telegram channel show dozens of students meeting with programme representatives at the university.

"Based on the available data, up to 800 women from various countries may have joined the programme since 2022,” the report states.

Initially focused on African recruits, the programme has since expanded its global reach, now targeting 84 countries. GI-TOC says the recruitment strategy specifically targets young women aged 18–22, based on perceptions of “female accuracy”, patience, and manageability.

Inside the war economy

Several participants reported that they were never informed about working in weapons production until after their arrival. Some believed they were enrolling in a legitimate work-study programme. They described long working hours, constant surveillance, exposure to harmful chemicals, and limited freedom of movement.

Whistle-blowers at Alabuga Polytech told Russian media that management was punitive and the working conditions were harsh. Some participants also spoke of racism, harassment, and intrusive monitoring.

While some participants described the experience as exploitative, others accepted the conditions, suggesting divergent perceptions of the programme.

"The fact that recruits work in drone production facilities places them, without informed consent, at risk in the Russia–Ukraine conflict,” the report notes. “They are not on the frontlines, but the SEZ has been targeted by Ukrainian drones aiming to disrupt Russian supply chains. Workers have been injured in such attacks.”

GI-TOC concludes that the Alabuga Start programme appears to meet several criteria for human trafficking, citing deceptive recruitment and exploitative conditions.

Mounting diplomatic pressure

In response, several African governments have launched investigations or distanced themselves from the programme. Some have suspended recruitment efforts or demanded explanations from intermediaries.

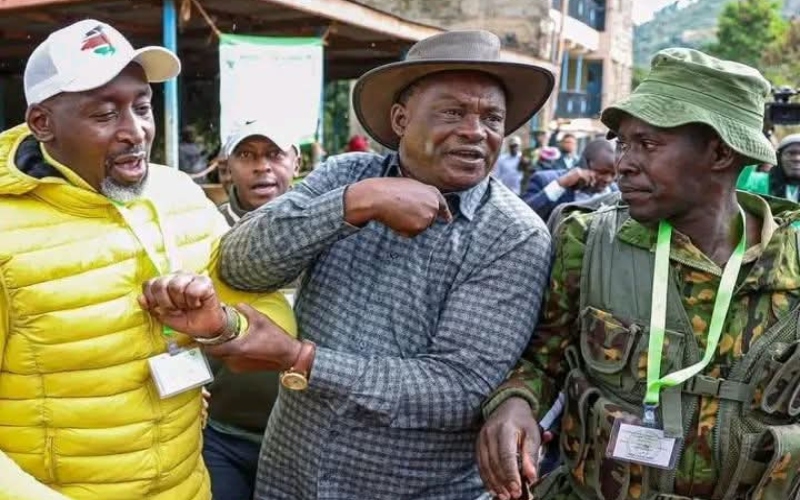

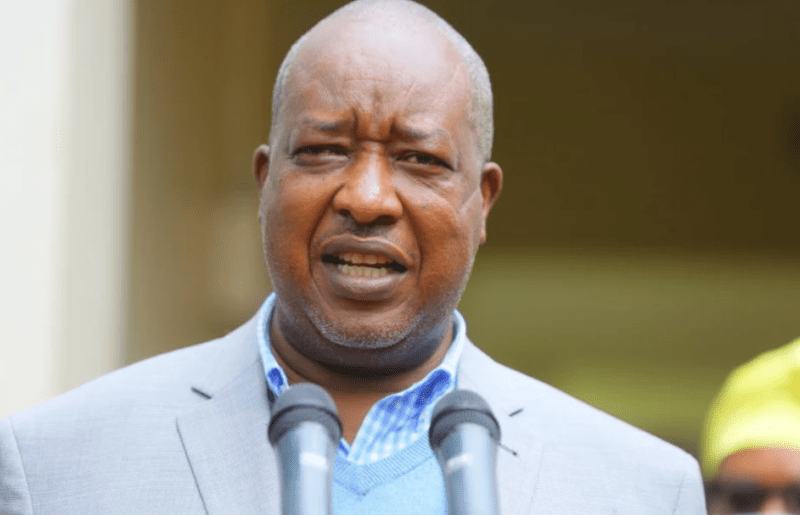

In Kenya, the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) has questioned officials from the immigration department over how Alabuga recruits obtained passports.

Some local intermediaries have since severed ties with the programme, apparently due to increased public scrutiny and concerns about reputational damage.

“Although Alabuga SEZ is technically a private enterprise, it is closely linked to the Russian state. The Russian Ministry of Defence is both the financier and end customer for Alabuga’s kamikaze drones. The SEZ itself is owned by a government department in the Republic of Tatarstan,” the report notes.

“It represents the kind of grey-zone public–private partnership that defines Russia’s war economy under Putin. While Alabuga Start may not be a state-directed initiative, it appears to benefit from Russian diplomatic presence in its recruitment countries.”

GI-TOC relied on evidence from around 60 current and former participants, as well as government officials from Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, and Russia. Some interviews were conducted in person between December 2024 and March 2025, with others done remotely.

Top Stories Today