Nowhere to run: How girls escaping harm still find themselves in unsafe spaces

But the reality remains grim. While SHOFCO’s safe houses provide essential resources for healing, counselling and education, their ability to care for these girls is limited by a lack of space and funding. The number of girls in need continues to rise, while the resources available to help them remain far too few.

As the world marks the International Day of the Girl, the celebration is bittersweet for many girls living in Kenya’s urban informal settlements.

While the day highlights progress made in advancing girls’ rights, it also underscores the harsh realities that continue to plague many of them.

More To Read

- Maasai community leads change as elders endorse fight against FGM and early marriage

- Ending violence against women ‘a matter of dignity, equality and human rights’

- Stakeholders warn of increased FGM cases in Wajir during long school holiday

- Gender CS Cheptumo calls for collective action against teenage pregnancies

- From silence to strength: The Kenyan women ending FGM and early marriages

- Bold, diverse and unstoppable: Girls speak out amid a world in crisis

Child marriage, female genital mutilation (FGM) and physical abuse remain ever-present threats. And for those fortunate enough to escape these horrors, another danger often awaits: having nowhere safe to go.

Many girls who flee violence often find themselves caught in another trap which is the absence of safe shelters and support systems. With the number of safe houses severely limited and resources stretched thin, many are forced to return to the very homes or communities they escaped.

Erick Onyango, a gender advocate with SHOFCO, an organisation dedicated to providing critical rescue services for at-risk girls in Nairobi, says there are only three safe houses available. “Yet the demand for support is overwhelming.”

Despite SHOFCO’s best efforts, the organisation is unable to keep up with the rising number of girls seeking refuge from violence and abuse.

The organisation rescues girls facing early marriages, sexual violence and physical abuse. Yet despite their dedication, the demand continues to outstrip capacity.

Onyango says girls arrive emotionally shattered and too terrified to speak. They bear deep emotional scars, often inflicted by both family members and the very communities they grew up in.

“Some are beaten by their own mothers. Some are raped. Others are simply abandoned. When we take them in, we’re not just offering shelter — we’re beginning a long journey of healing.”

Lack of resources

But the reality remains grim. While SHOFCO’s safe houses provide essential resources for healing, counselling and education, their ability to care for these girls is limited by a lack of space and funding. The number of girls in need continues to rise, while the resources available to help them remain far too few.

“If we can’t trace the family, or if the home is unsafe, we provide long-term care,” he explains. “But many safe houses have closed down due to funding constraints. We’re being asked to do more with less.”

In some cases, the abuse comes from the very mothers who are meant to protect their children. Onyango points out that these mothers, often survivors of trauma themselves, continue the cycle of violence. Many live in extreme poverty, and their unhealed emotional scars sometimes manifest as abusive behaviour towards their children.

He notes that SHOFCO’s approach is not just about removing the child from harm but also addressing the root causes of abuse. Family reconciliation, when possible, is a key part of their efforts.

The organisation offers counselling and economic support to help mothers heal and learn how to care for their children in healthier ways. “We don’t just rescue the child, we try to heal the family — if it’s safe to do so.”

However, systemic challenges persist. Too many families lack the resources to break free from the cycle of poverty and abuse. For these girls, there is often nowhere to turn once they leave abusive homes. Even the temporary safety of a SHOFCO shelter can be fleeting, leaving them at risk of returning to dangerous situations.

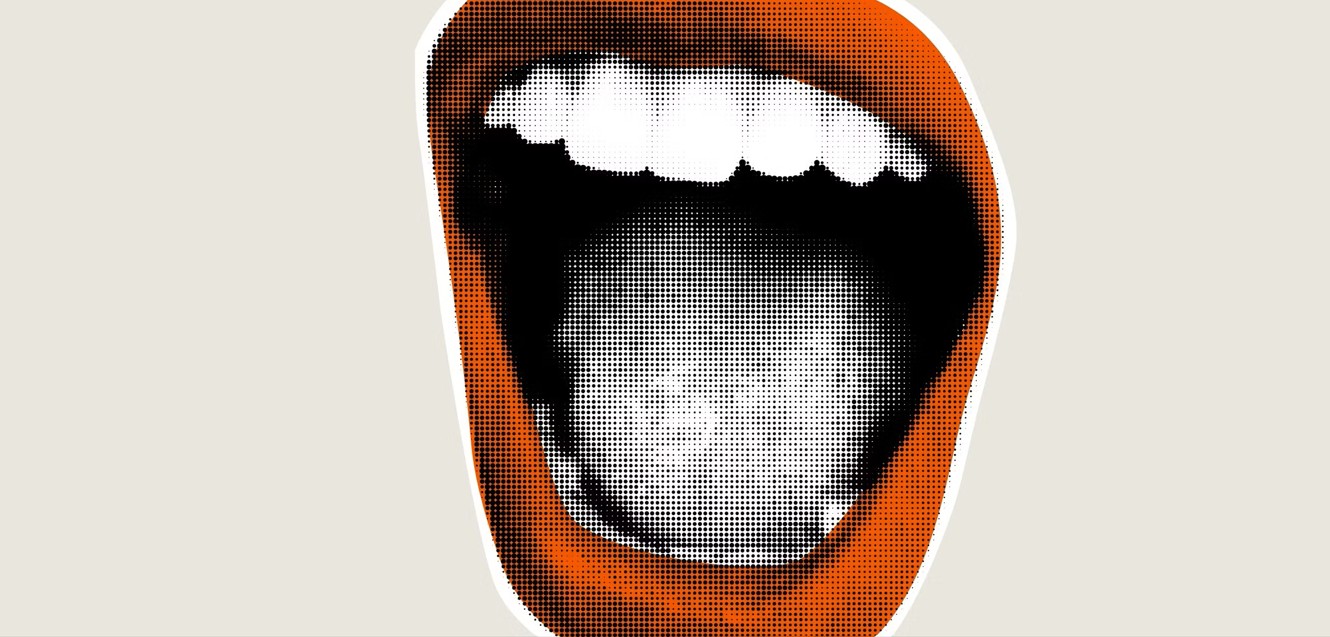

Culture of silence

For many girls, silence is the loudest barrier they face. In numerous communities, cultural norms encourage shame and secrecy around abuse. Families often prefer to resolve such matters within their own circles, making it harder for girls to speak out.

“Defilement, physical assault, incest — these are things we hear about every month. But most cases go unreported. Families fear shame. Girls are told to stay quiet,” says Onyango.

This culture of silence means that many girls are never heard, and the cycle of abuse continues. Girls are made to feel that speaking up would dishonour their families, further deepening their isolation and trauma. When they finally find the courage to report their abuse, they often face judgement, blame and even punishment.

For those who manage to access support, the road to recovery is long and difficult. Obstacles abound — from lack of legal support to stigma and the fear of further harm.

While SHOFCO’s safe houses offer temporary respite, the world outside remains dangerous. In nearby Biafra, a young woman’s daily reality is fraught with risks.

Hafsa Hussein, an advocate for young women’s rights, works closely with girls in this community. She knows firsthand how hard it is to survive in a neighbourhood where both physical and sexual violence are constant threats.

“Girls are afraid to go to work or even walk home after dark,” Hafsa says. “It’s not just about FGM or child marriage — it’s also about not being able to move safely in your own neighbourhood.”

Without adequate street lighting, police presence or safe public spaces, girls remain vulnerable to predators. Hafsa urges the government to invest more in public safety and ensure that health centres are properly staffed and equipped to meet the needs of these girls.

“We need to empower girls with knowledge of their rights. We must also include boys in this conversation. They need to be taught to respect and protect — not to harm.”

For girls who are undocumented or come from foreign backgrounds, the risks are even greater. Many of these girls are invisible within the system and lack legal protection.

Terresia Wairimu, an advocate for sexual and reproductive health rights, has worked with numerous girls in this vulnerable situation and has seen many fall through the cracks.

“These girls are terrified to report abuse because of their immigration status. They have no voice and no legal protection.”

Local health centres often fail to serve these girls adequately. They are either turned away or, knowing they have no rights, avoid seeking help altogether. The fear of deportation or being returned to abusive environments keeps them trapped in a cycle of silence and neglect.

“They go to clinics and are turned away. Or they don’t go at all because they know there’s no medication or trained personnel. We are failing them.”

Hope in the face of adversity

Despite the overwhelming challenges, Onyango, Hafsa and Wairimu remain committed to fighting for a safer future for girls. They continue to push for systemic change — greater funding for safe houses, better access to education, and a society where girls and women can live freely and safely without fear.

But they also acknowledge that society and the government must do more. It is not enough to rescue a girl and offer temporary shelter. What is needed is a community-wide effort to break the cycle of violence, heal trauma and create opportunities for girls to thrive.

“Every girl deserves to grow up free from fear, free from abuse, free to dream. And that shouldn’t be a privilege — it should be a right,” Hafsa says.

As the world reflects on the progress made and the work that remains, many girls are still waiting for safety, for justice and for a future they can call their own.

Globally, more than 370 million girls and women, about one in eight, have experienced rape or sexual assault before the age of 18. When non-contact abuse such as verbal or online harassment is included, the figure rises to 650 million. Meanwhile, one in five girls is married before turning 18, cutting short their education, safety and opportunities.

Girls aged 15 to 19 are twice as likely as boys to be out of education, employment or training. In fragile contexts, they are nearly 90 per cent more likely to be out of school than girls in stable settings.

Nearly one in four girls aged 15 to 19 who have been in a relationship have experienced intimate partner violence. Among young women aged 20 to 24, one in five were married as children with child marriage rates almost double the global average in fragile settings.

Top Stories Today