Northern Kenya residents push for recognition of hero David Wabera

Their plea is that the courageous administrator be given a befitting honour for defending Kenya's unity and paying the ultimate price.

Kenyans who visit Nairobi will most likely come across Wabera Street, right in the centre of the city, which branches out of Kenyatta Avenue and ends at the City Hall Way roundabout, directly facing the Supreme Court building.

Many city residents and visitors probably do not know whom the street was named after. But for most residents of northern Kenya, the name Wabera rings a bell. The street in the capital city bears the name of one of their own; a hero.

More To Read

- Wajir police nab suspect with AK-47 rifle in ongoing crackdown on illegal firearms

- Northern region MPs accuse President Ruto of ignoring region in State of the Nation Address

- Diamond Trust Bank lands in Garissa, ignites push for financial inclusion in northern Kenya

- Northern Kenya mourns Raila, remembers his legacy of inclusion and justice

- Treasury rolls out new plan to expand financial inclusion in Northern Kenya

- Multi-agency team recovers 17 stolen goats in Marsabit, suspect arrested

When the National Heroes Council started preparations for a strategic plan that would help in coming up with an elaborate framework for the identification and recognition of Kenya’s heroes, the residents of northern frontier counties had one plea: that their hero, David Dabasso Wabera, be given a befitting recognition as one who patriotically defended Kenya’s unity and paid the ultimate price.

Wabera’s name triggers memories of historical injustices visited on innocent people of northern Kenya.

As the agitation for Kenya’s independence grew in the late 1950s, a young clerical assistant had been hired by the colonial government in Marsabit to help Mervyn Maciel, a newly posted clerical officer at the district commissioner’s office.

Young Wabera was full of energy as he served in Maciel’s office. As an African office assistant, he faced the moral dilemma of choosing between supporting the agitation for a breakaway northern frontier or the yet-to-be-formed Kenyan state.

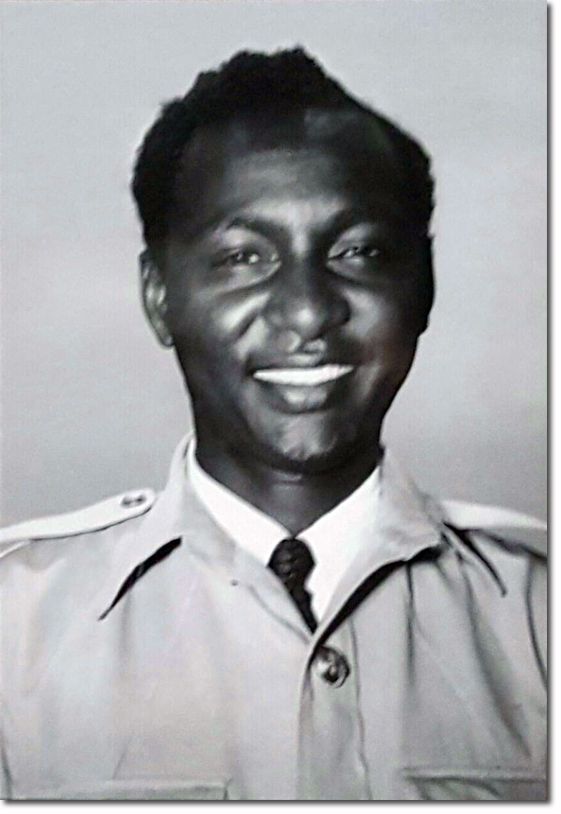

In his book titled Bwana Karani: The Life and Times of Mervyn Maciel in East Africa, Maciel notes nostalgically that he will never forget the first day he entered the DC’s office in Marsabit as district clerk in 1949 and met David Dabasso Wabera.

“The DC (Mr Gerald Bebb) was away on safari, and on entering the office, I immediately noticed a handsome young man coming towards me and introducing himself as David Dabasso,” says Maciel.

Wabera came from the Gabbra tribe and seemed very much at home working in his own district. But all this was to change in a few months.

Wabera was not entirely happy with his job as he wanted to be moved to his home area.

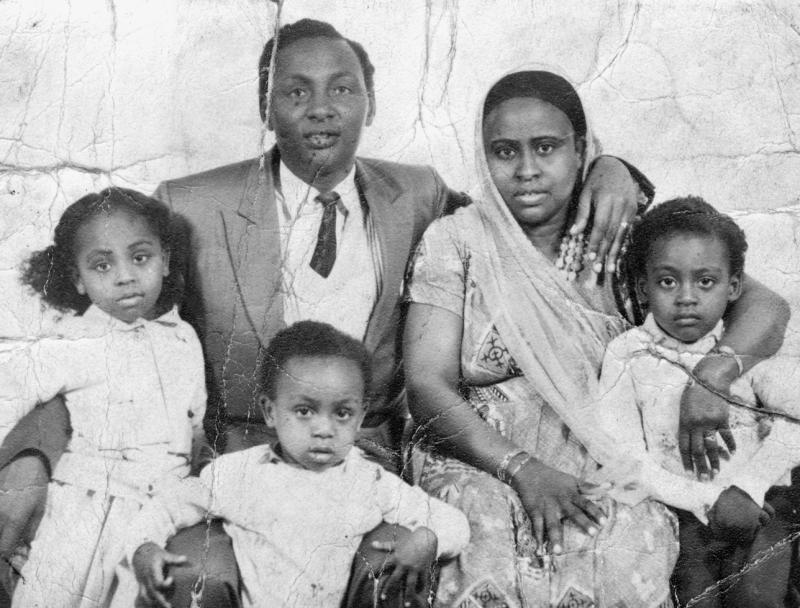

David Dabasso Wabera. Wabera’s name triggers memories of historical injustices visited on innocent people of northern Kenya.

David Dabasso Wabera. Wabera’s name triggers memories of historical injustices visited on innocent people of northern Kenya.

“It was only some months after I had arrived that I found out that David was not too happy to remain in Marsabit. This was chiefly because of the many domestic problems facing him; being a government employee and having most of his family around him, there were endless demands for financial assistance,” says Maciel.

Efficient worker

Described as an efficient and willing worker, Wabera was good at drafting routine letters as he also spoke excellent English.

As Kenya was preparing for independence, and in preparation for the big challenges that lay ahead, several African administrative officers were sent to Britain for further training.

Wabera was one of the lucky ones to go to Britain for the training. Several months after returning from the UK, he was posted to Isiolo as district commissioner.

But his brilliant career was cut short while serving in Isiolo.

At this time, there was a lot of tension in the north as Somalis sought to secede from Kenya, an idea that President Jomo Kenyatta would not entertain.

While on safari within Isiolo in June 1963, and in the company of Senior Chief Haji Galma, a hail of bullets was fired by secessionists, killing both Wabera and the chief.

Before Wabera’s untimely death, the mood in the country was euphoric. Finally, after 70 years of colonial domination, the yokes of oppression had been shattered and a new crop of African leaders was steering Kenya into the community of nations as the newest independent state.

As most parts of the country eagerly waited for the all-important moment when the colonial flag would be lowered, residents of the Northern Frontier District — one of the regions of British Kenya — were jittery, unsure of what the new state would have for them.

Wabera Street in the Nairobi Central Business District. (Photo: Africa-expert)

Wabera Street in the Nairobi Central Business District. (Photo: Africa-expert)

A few months earlier, in 1962, some residents of northern Kenya had tried to break away from Kenya, convinced that they would be better off if their region was merged with the State of Somalia.

Kenya’s political leadership would hear none of that and were determined not to yield even an inch of the Kenyan soil to their more aggressive neighbour, Somalia.

Referendum

The government had just won a referendum called to determine whether the region was to remain in Kenya or be allied to Mogadishu.

The Kenyatta regime had won the game of numbers but it was yet to conquer the minds of the residents who felt they would be better off if they were administered from Mogadishu.

“My dad had been posted there (Isiolo) to ensure there was peace and harmony but some British officers were unhappy. They hatched a plan to teach him a lesson and plunge the region into turmoil and make it ungovernable,” says Said Wabera, a son of the late Wabera.

A few days after Kenya marked its first Madaraka Day, Wabera visited the area for a meeting with local residents, accompanied by Chief Galma Dido. And as the government agents wound up their speeches, three assassins lay in wait in a thicket.

As the entourage left Sericho, the three gunmen, believed to have been acting on the orders of a senior leader from Somalia, singled out the two administrators and killed them.

The officers attached to the district commissioner were unhurt. The assassins then left and drove towards the Kenya-Somalia border.

When President Kenyatta learnt of the development, he was livid with anger against Mr Pridgeon, the assistant commissioner of police who was in charge of the Northern Frontier region.

The tragic turn of events that led to Wabera’s murder is noted in the Peace Bulletin edition of April 2005: “Six months to independence, a bullet that triggered a series of Kenya’s political assassinations was fired from a Patchett sub-machine gun along the Isiolo-Wajir border on June 28, 1963. A senior civil servant and a chief, while on their way back from government duty in Sericho, Isiolo District, were brought down by a hail of bullets fired by secessionists who later fled to Somalia in a Land Rover.”

It is hoped, especially in northern Kenya, that Wabera is one of Kenya’s heroes who will be recognised in new government plans.

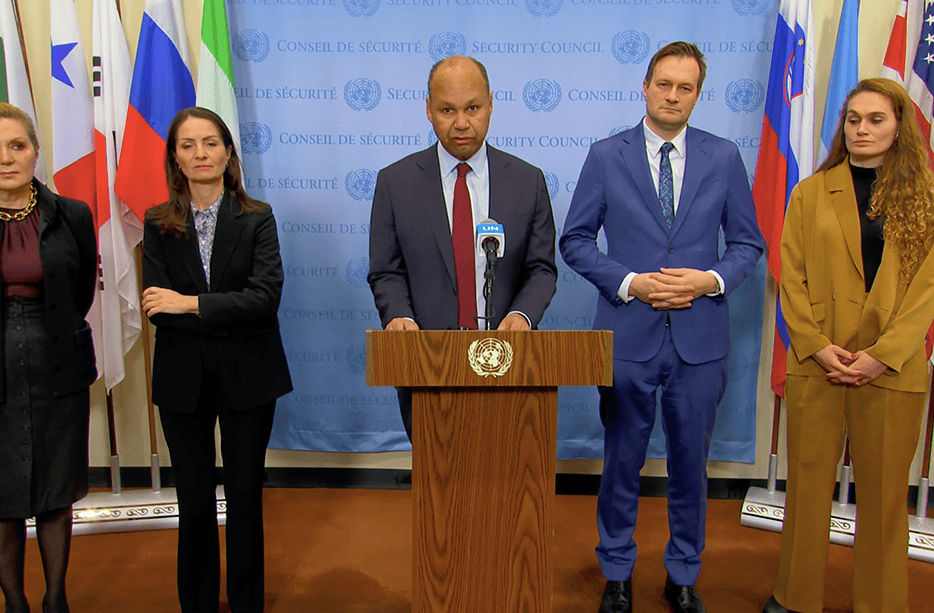

Charles Wambia, the CEO of the National Heroes Council, says there are still many questions regarding many Kenyans who have not been recognised despite their immense contribution in different fields and the sacrifices they made for the country, saying these are some of the grey areas that they seek to address.

“We are in the process of gathering views from the public to guide our activities as we seek to operationalise the strategic plan in July in preparation for Mashujaa Day celebrations later in the year,” he says.

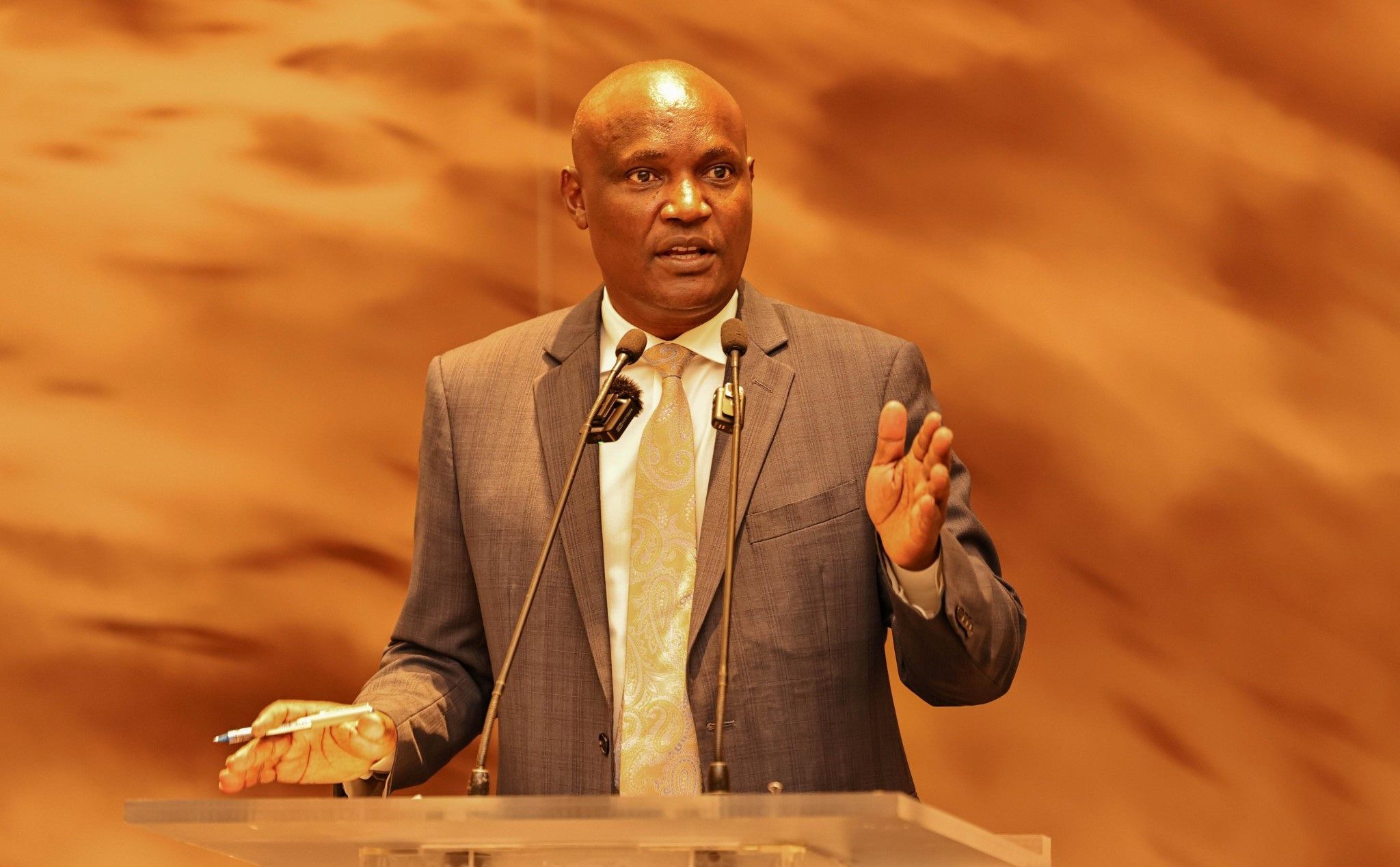

Daudi Tari Abukula, a local leader from Isiolo, says the northern part of Kenya has been marginalised in terms of proper recognition of its heroes and sacrifices made for the nation.

He singled out the Shifta War, in which ethnic Somalis in the Northern Frontier District attempted to take over northern Kenya from Isiolo upwards.

“There are people who died protecting the Kenyan territory against the secession attempt — alongside Daudi Wabaso Wabera who was the first African DC in Isiolo — who have never properly been recognised. We want them honoured well,” he said.

Top Stories Today