Tundu Lissu on death of Ngugi wa Thiong'o: A prisoner's eulogy from Ukonga prison in Dar es Salaam

He started his long literary career as James Ngugi, but soon dropped the ‘James’, becoming the Ngugi wa Thiong’o known to the world, and in keeping with his Gikuyu naming customs.

On the early morning hours of Wednesday, May 29, the BBC announced the death, in the United States, of Prof. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, perhaps Africa’s greatest writer of all time. He was 87 years of age.

His career as a writer and teacher covered the entire period of post-independence East Africa. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, as he was simply called everywhere around the world, had a huge cultural influence on the whole generation of African youth who came of age in the 60s, 70s and 80s.

More To Read

- Tanzania’s opposition leader Tundu Lissu ‘isolated’ in Ukonga Prison, claims Chadema

- Tanzania dispatches envoy to Brussels to avert Sh23.3 billion EU aid freeze

- European Parliament moves to block Sh23.44 billion aid to Tanzania after post-election violence

- Tanzania dismisses EU sanctions threat over human rights violations

- Tanzania challenges EU debate on Tundu Lissu and post-election crisis

- US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations calls for probe into Tanzania election violence

I’m not so sure it is still the case today, but throughout the 70s and 80s, his novels (for there were many!) – Weep Not, Child; The River Between; A Grain of Wheat; Petals of Blood, and many more – were mandatory readings in Tanzania’s secondary school literature classes.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o was a cultural nationalist writer, poet and thinker of the very highest order. A contemporary of two other African literary titans, the Nigerians Chinua Achebe and Nobel Literature Laureate Wole Soyinka, but, unlike them, Ngugi was the majestic and unabashed exponent of the use of African language in African literature.

And, he prolifically walked his talk. After the catharsis of his imprisonment by Mzee Jomo Kenyatta for writing Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), the Gikuyu play critical of Kenyatta's post-colonial authoritarian regime, Ngugi switched completely to writing in Gikuyu, his mother tongue.

Ngaahika Ndeenda was soon followed by Caitaani Mutaharaba-Ini (Devil on the Cross), Murogi wa Kagogo (Wizard of the Crow), Matigari ma Njiruungi (Remains of Bullets), The Black Hermit, The Trial of Dedan Kimathi and many other memorable plays which went on to be translated into dozens of the major languages of the world.

Like other cultural nationalists of his era and even earlier period, Ngugi wa Thiong’o rejected the use of alien names imposed and borrowed from other cultures. He started his long literary career as James Ngugi, but soon dropped the ‘James’, becoming the Ngugi wa Thiong’o known to the world, and in keeping with his Gikuyu naming customs.

By his example and sheer personality, Ngugi thereby recovered our cultural humanity as Africans. He made us proud of, and even comfortable with, using our own African names. He made us to think and identify ourselves as Africans in our multiple diversities.

Ngugi’s deep and abiding cultural nationalism sprang, obviously, from his own people, the Gikuyu’s cultural, political and military resistance to British settler colonialism and its cultural baggage. I’m probably wrong here, but I believe that it was also partly influenced and fertilised by the long tradition of radical Pan Africanist and Afro-American political and cultural struggles of that era.

Ngugi had a deep influence on me personally & on my siblings too. Mzee Alute Mughwai, my eldest brother, started out as Simon Augustino, but after coming into Ngugi’s cultural orbit, he reverted back to Alute Mughwai. I, too, did the same.

Those I went to primary and secondary school with knew me as Antiphas Lissu. Today, thanks to Ngugi’s cultural whiplash, everyone calls me Tundu Lissu! All of my other brothers do not use their Christian names as their first name. It all has to do with Ngugi, even if they may not know it.

Ngugi’s advocacy of the use of our own native language in public affairs and in educational and literary spheres has faced greater resistance because of the deeply ingrained European and Western cultural hegemony in our Africa. It has nonetheless made significant strides across the continent, as evidenced by the official recognition and encouragement of the use of African languages in several African Constitutions.

This prodigal son of the Gikuyu and a child of Africa, who taught us fellow children to weep not; who sang to us lovely songs about our beautiful hills and ridges, and the rivers between them; who exhorted us to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery bydecolonising our mind; and who instructed us not to accept forced marriages of postcolonial settlements made in Lancaster House, but to marry if and when we want, is no longer with us on this physical earth.

But, his spirit lives on, and his memory will live on in the hearts and minds of the millions of African children he loved so, wherever they may be. This great thinker and revered teacher has now ceased to think.

We won’t hear his teacher’s voice again. But his thoughts and teachings are timeless. They will live on wherever and whenever men and women struggle for justice and self-determination in the Africa he loved so.

Other Topics To Read

- Opinion

- Ngug'i wa Thiong'o

- Tundu Lissu

- chadema

- CHADEMA party leader

- Weep Not

- Child

- The River Between

- Petals of Blood

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o dead

- I Will Marry When I Want

- Devil on the Cross

- Wizard of the Crow

- Remains of Bullets

- Grain of Wheat

- Tundu Lissu on death of Ngugi wa Thiong'o: A prisoner's eulogy from Ukonga prison in Dar es Salaam

- Headlines

May his soul rest in deserved peace amongst his Gikuyu ancestors.

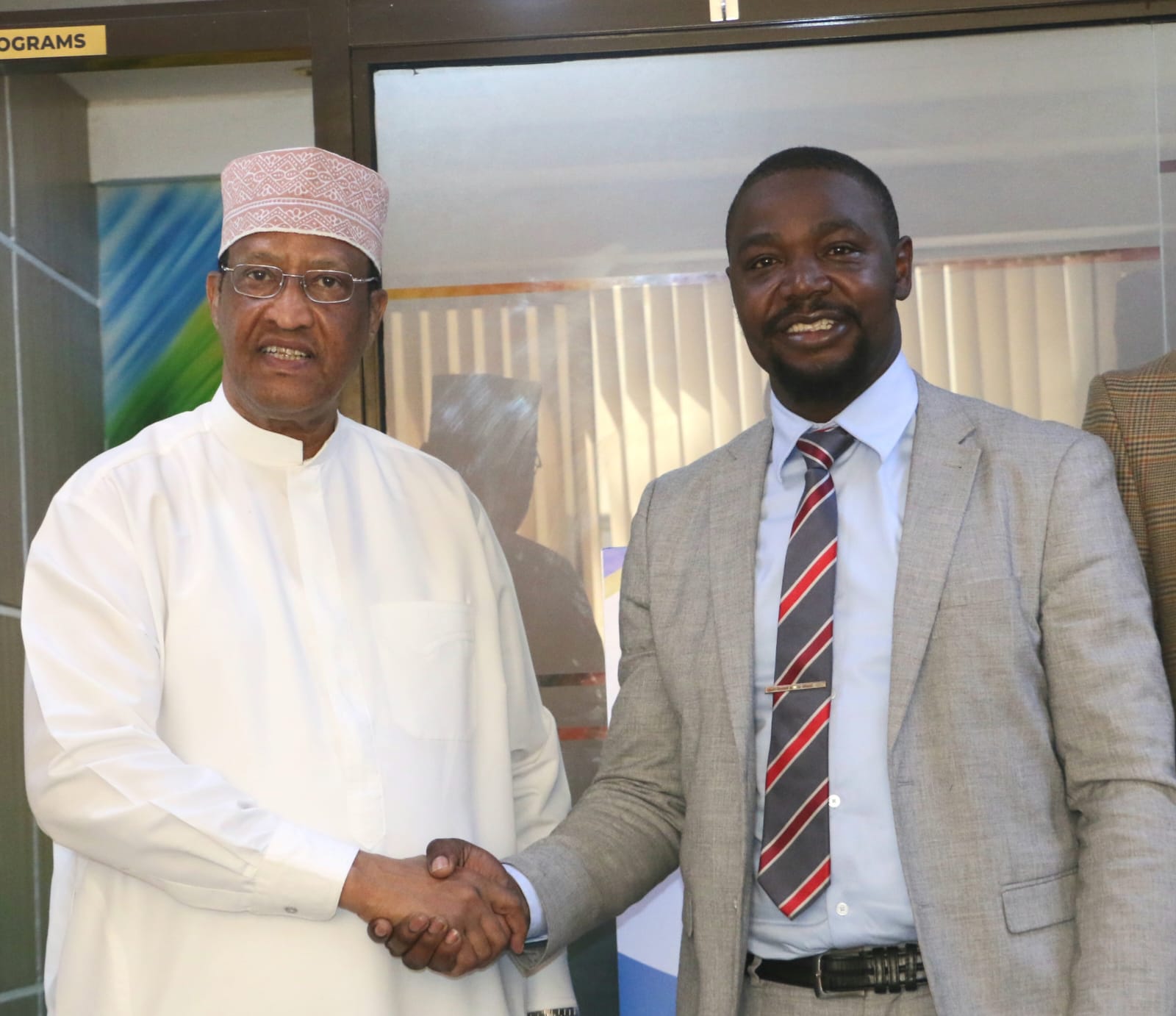

Tundu Lissu is a former presidential candidate and the chair of Tanzania’s main opposition party, CHADEMA which has been barred from participating in this year's election. He has been held in indefinite detention since April 2025, accused of treason for demanding electoral reforms — a charge widely seen as part of the government’s clampdown on dissent.

Top Stories Today