Delivering in fear: The untold impact of disrespect in childbirth

26.7 percent of the young mothers reported being shouted at, insulted, or mocked—forms of verbal abuse that can leave deep emotional scars.

For Dorothy Auma (not her real name), the verbal insults and judgment from the healthcare system began long before she entered the delivery room - they started during the antenatal visits she had come to dread.

Each appointment felt less like seeking care and more like standing before a tribunal. At the local clinic, staff who had once treated her kindly - as a child, a schoolgirl, a familiar face in the community - now looked at her with quiet contempt. The whispered remarks cut deeper because they came from people she had once trusted.

More To Read

- The harsh reality of maternity leave, breastfeeding challenges for Kenya’s informal workers

- From near death to lifesaver: How surviving postpartum haemorrhage inspired Kenyan midwife’s mission

- ‘Machozi ya mwisho’: A grieving father’s mission to end preventable baby deaths in Kenya

- Hidden risks of over-the-counter drugs in early pregnancy

- ‘They told them I was dead': A mother’s pain and the mental toll of family separation on children

- One in five Kenyan adolescents suffers childhood trauma, study reveals

At just 17 years old, Auma* was no longer seen as a girl in need of care - she had become a cautionary tale. The questions directed at her rarely focused on her health; instead, they carried thinly veiled judgment:

“Where is the father?”

“Why didn’t you think before doing this?”

The atmosphere made it nearly impossible to ask questions or voice her fears. When she tried, she was often met with cold instructions, sharp tones, and indifference.

Outside the clinic, the experience was no different. Friends were warned not to "end up like her." At home, the disappointment was even heavier; sighs and averted eyes spoke louder than any words: you’ve let us down.

“People wouldn’t say anything directly,” Auma* says. “But the stares, the silence… they made sure you knew you weren’t welcome. It’s like they wanted you to feel ashamed.”

She wasn’t just judged - she was denied care. Health attendants told her to return with an adult: either a parent or the man who had impregnated her. But for many girls like Auma*, that simply wasn’t an option.

“They say, ‘Go and come back with your parent or the one who made you pregnant.’ But at home, your parents are mad too. They say, ‘You’re big enough now - go get your treatment.’ So you’re stuck in the middle, with nowhere to turn.”

She remembers being asked for an ID card - something she didn’t have and being turned away. No one explained her rights or how to get help. There was no kindness, no guidance, only judgment.

“No one explains anything. You're expected to know everything. But how can you ask when everyone looks at you like you’re already a failure?”

Even before her due date, Auma* began experiencing complications. The physical pain was real, but it was the emotional weight of isolation and fear that nearly broke her. Still a child, trying to bring another life into the world, she was met not with care but with ridicule.

When labour finally came, the delivery room offered no refuge. Instead of empathy, she encountered commands, cruelty, and shame.

“They don’t treat you like a mother in labour. They treat you like someone who should be punished,” she recalls. “One nurse told me, ‘Open your legs and stop disturbing people —you should have closed them in the first place.’”

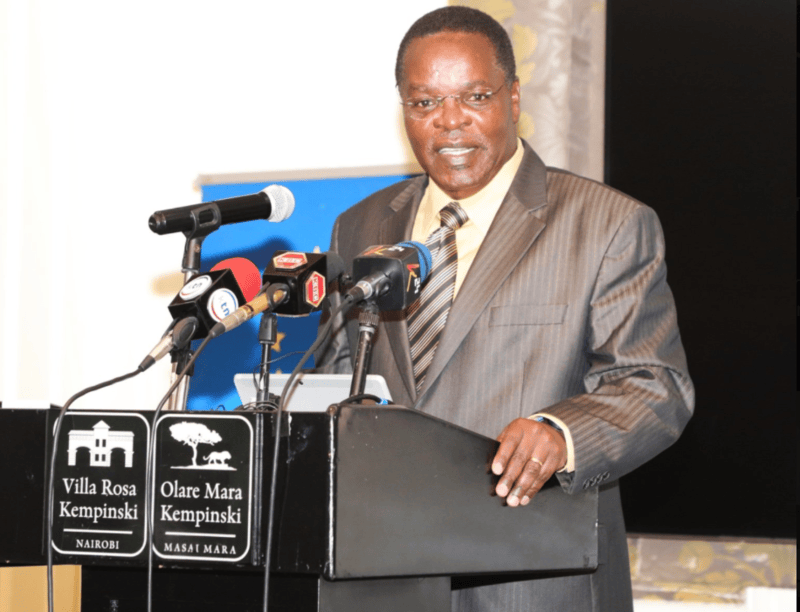

Dorothy Auma* is traumatised by the ordeal. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Dorothy Auma* is traumatised by the ordeal. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Auma* says she didn’t even feel like a person. She felt like a burden - an inconvenience to be dealt with.

“It’s hard to even ask for help,” she says. “If you scream too loudly, they say you’re being dramatic. If you’re quiet, they say you’re wasting their time. You don’t know what to do.”

Now her baby is barely three months old, and she still wrestles with fear, pain, and loneliness; the absence of compassion during delivery turned a terrifying moment into a traumatic one.

“It was one of the hardest and most terrible experiences of my life,” Auma* says softly. “I still don’t know how I survived it.”

As the world slowly healed from the grip of the pandemic, Sarah Magove* stepped into a different kind of crisis, giving birth to her second child in an overcrowded public referral hospital where care had been stretched thin.

What she hoped would be a safe delivery turned into a fight for space, dignity, and basic support in a system already buckling under pressure.

Magove* went into early labour just after midnight and, with mild pain and no one to accompany her, walked alone to the nearby hospital. But instead of care, she was met with cold procedures - denied admission because she couldn’t afford a required scan. With labour still in its early stages, she was told to return home.

By mid-morning, the pain had grown unbearable. When she returned to the hospital, she found herself in the middle of what felt more like a crisis zone than a maternity ward - overwhelmed staff, overcrowded rooms, and women crying out in pain with little or no assistance.

“Only when the baby’s head was visible would someone rush over.”

Medical attention was based on urgency; unless a woman was actively delivering, she was overlooked. First-time mothers, unsure of what to do, were left behind. Shyness was seen as weakness.

When Magove* was finally admitted into the labour ward, there were no beds. She had to wait her turn, despite being in full labour. The few staff on duty did their best, but it was impossible to meet the needs of so many.

“There was no privacy. You delivered your child and then had to move immediately because someone else was already waiting.”

After delivery, Magove* and the other new mothers had no designated space to rest or bond with their newborns.

“You just wrapped your baby in a leso, held on, and waited.”

Sarah was discharged just a few hours later. She paid Sh400 - not because the hospital offered support, but because they needed the bed.

“There was no check-up, no counselling, no one asking if we were okay. You were handed your baby and told to leave.”

“I survived. My baby survived. But many don’t. And even those who do - we carry the trauma. That hospital, that day… it changed how I see childbirth forever.”

While maternal health services have expanded over the years, growing evidence shows that disrespect and abuse during childbirth remain alarmingly common, particularly in public health facilities.

A 2022 cross-sectional study conducted in Korogocho, one of Nairobi’s informal settlements, offers a stark look into the reality faced by adolescent mothers. The study focused on girls aged 10 to 19 and found that over 32 per cent reported experiencing abuse by healthcare providers during childbirth. The abuse ranged from verbal and physical mistreatment to discrimination and neglect.

26.7 per cent of the young mothers reported being shouted at, insulted, or mocked - forms of verbal abuse that can leave deep emotional scars. 7.5 per cent experienced physical abuse, including slapping or rough handling, while in labour.

15.1 per cent reported stigma or discrimination, often due to their age or marital status. Even more troubling, 17 per cent said they were detained in the facility after delivery because they or their families were unable to pay hospital fees.

For adolescent mothers - a group already vulnerable due to societal judgment and limited resources - such treatment can have long-term psychological and health consequences. Many fear returning to health facilities for future care, while others internalise the mistreatment, feeling shame rather than support at a time when they most need protection.

This is not an isolated phenomenon. A 2016 study involving 49 maternity care providers in Western Kenya revealed that over half had either witnessed or engaged in verbal abuse, and more than one-third admitted to physically mistreating women during labour. These findings point to a disturbing culture where mistreatment is normalised, even by those who are meant to uphold standards of care and compassion.

This national reality mirrors findings from global research. A 2019 study by the World Health Organisation (WHO), which examined childbirth experiences in four countries - including Nigeria and Ghana - found that over 40 per cent of women experienced physical or verbal abuse, stigma, or discrimination during childbirth.

Most strikingly, the study revealed that over 75 per cent of episiotomies and 60 per cent of vaginal examinations were carried out without informed consent. In some cases, women were cut, touched, or examined without being told what was happening or why - a clear violation of their rights and autonomy. Non-consensual care - particularly during such a vulnerable moment - strips women of dignity and control over their bodies.

Top Stories Today