From waste to water tanks: How Kariokor youth are turning Nairobi’s trash into livelihoods

Containers arrive in grimy, greasy, and unwashed condition. There’s no sophisticated equipment—just human effort, soap, water, brushes, and a lot of hard scrubbing.

I had always been curious about the yellow and white mitungi (jerrycans) neatly stacked along Ring Road in Kariokor, especially when heading toward Nairobi’s Machakos Bus Station.

But it was not until my house ran out of water and I found myself scrambling to find jerrycans that those containers took on new urgency. I noticed them again, more sharply, now on my way to town.

More To Read

- Kalembe Ndile and the Kariokor tyre men: A story of survival, skill and silent impact

- Thread by thread: Kariokor’s women weavers stitch culture, resilience, and hope into every bag

- Forging the future: How Kelvin Kimuyu is reviving brass craft in Nairobi’s Kariokor Market

- Kariokor residents protest over garbage, burst sewers and Sakaja's inaction

- Mazingira Day: How Kariokor's old tyres dealer is helping safeguard environment

- Unbowed: Umeme FC’s battle to maintain club’s rich heritage amid financial difficulties

Unlike many Nairobi residents, I hadn’t invested in a water tank or mitungi—until a sudden shortage made water storage a personal necessity.

So, when the opportunity arose to report on the story behind these ubiquitous containers, it felt less like an assignment and more like fate, especially since I left the interview with a jerrycan tucked under my arm.

It was a chilly Thursday morning when I visited Kariokor Market with videographer Justin Ondieki.

Amid the clanging of metal tools, the honking of cars and buses heading into town, and a steady drizzle soaking the makeshift wooden stalls, we met a group of young men whose work goes far beyond simply selling used drums.

Among them were Brian Musembi and Mike Muchaka, both 23, who greeted us warmly.

We chatted briefly, and they soon recommended we speak to someone special: Robinson Chege, better known as "Price Chege (Drum)" on TikTok.

Before we headed over to Chege, Musembi and Muchaka gave us a glimpse into their world.

Musembi explained that the drums and mitungi come from all over Kenya—industrial soap factories, hotels, households, and especially Nairobi’s Industrial Area. Some are even sourced through garbage collectors or street children, who sell them for a small fee.

"We buy everything you see here; we are not given for free. Then we have to clean and resell it, so the margin is small. But it is something, right?" Musembi said.

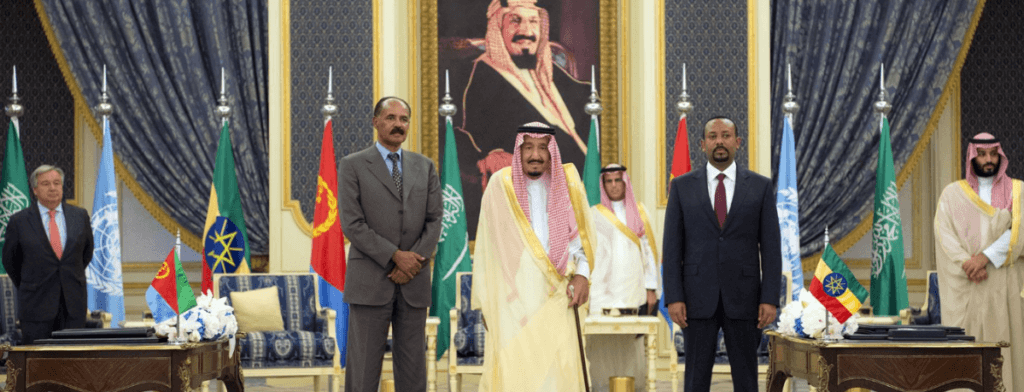

Containers arrive grimy and unwashed, cleaned not with machines but with soap, water, brushes, and sheer human effort. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Containers arrive grimy and unwashed, cleaned not with machines but with soap, water, brushes, and sheer human effort. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

The business of waste

The smallest containers, like ketchup or sauce bottles, sell for as little as Sh50, while medium-sized jerrycans used for oil range between Sh100 and Sh250. Larger plastic drums fetch between Sh1,000 and Sh2,500, with metal drums going for around Sh1,500. Even massive chemical containers are washed and repurposed as tanks, storage tanks, or, when cut in half, water troughs for animals, especially farmers or pastoralists.

They, however, told me that they also have drums that they source from Kamukunji as well.

As Musembi wiped rainwater off a drum with the edge of his sleeve, the conversation shifted to prices and how they’ve changed over time. He chuckled and shook his head, recalling a recent customer.

"There was this guy who came in last week. Walked straight up, pointed at a drum and said, 'Nipe hii ya 700, just like last time.' Turns out he’d bought one in 2018 for Sh700."

Musembi let the memory settle.

"When I told him it’s now going for Sh1,000, the guy looked like I’d slapped him. Completely shocked."

He laughed again, but his tone grew serious.

"But what do people expect? The price of everything has gone up, including transport, the cost of getting the containers, and even soap for cleaning them. We don’t raise prices for fun. We’re just adjusting to survive. I’m sure he doesn’t buy unga ya ugali at the 2018 prices now."

The cleaning process

The cleaning process is cold, wet, and physically demanding.

Containers arrive in grimy, greasy, and unwashed condition. There’s no sophisticated equipment—just human effort, soap, water, brushes, and a lot of hard scrubbing.

"We wash them here in the rain, in the sun... this is our hustle and we are very much proud to do it," Musembi said, smiling through the drizzle.

Barely sheltered from the elements, Musembi and Muchaka sprang into action—scrubbing jerricans in the rain—after a customer ordered 50 twenty-litre yellow containers.

Earlier, I had noticed their hands—especially Muchaka’s—which silently told the story of their work: darkened by oil, roughened from constant scrubbing, calloused from heavy lifting, and marked with patches so dark they looked as if burned by acid.

He hesitated when asked to show his hands; he rubbed them together, as if trying to wipe away the stains, then held them up.

"These patches; they come from handling the containers every day, oil, chemicals, sun… it all leaves a mark, and not just on the skin," he said as he turned his hands over

He paused, eyes lingering on the hardened grooves in his palms, as if retracing every scrub and lift. Then he looked up, voice steady but low.

"Sometimes I hide them, especially when someone asks what happened to them, but at the end of the day, these hands feed me. This job puts food on the table, keeps me alive; that is what matters."

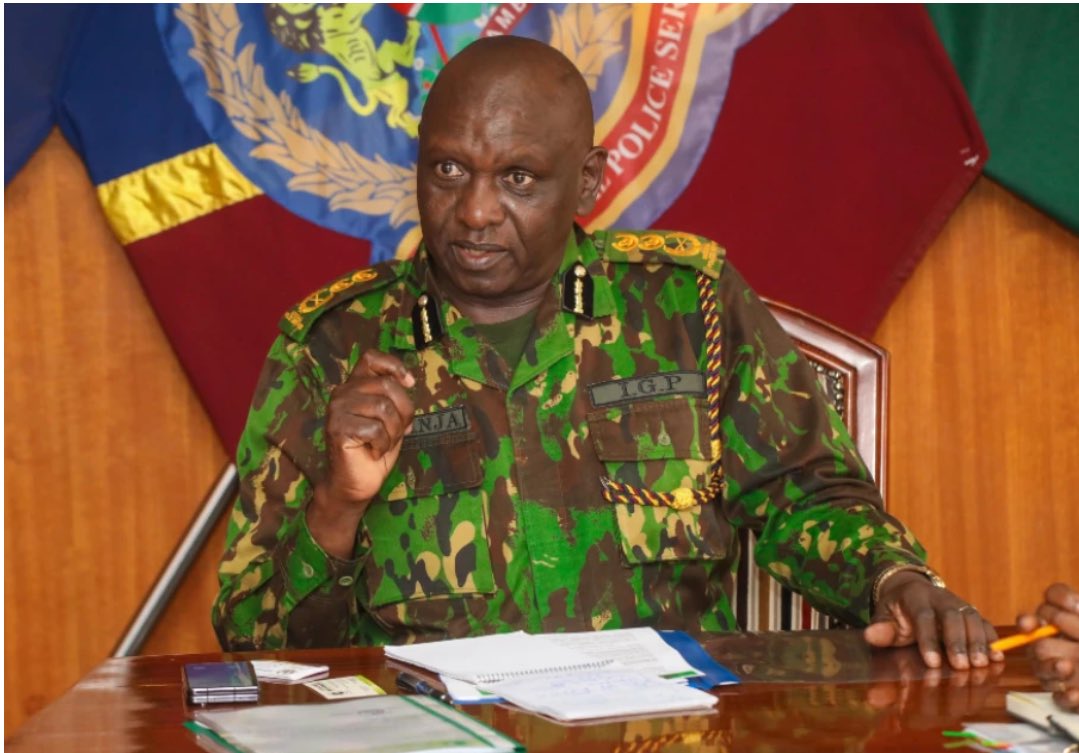

Community attitudes are mixed—some admire the traders’ resilience while others mock their work as dirty, but neither scorn nor stigma deters them. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

Community attitudes are mixed—some admire the traders’ resilience while others mock their work as dirty, but neither scorn nor stigma deters them. (Photo: Justine Ondieki)

A lifeline

For them, it's more than just a hustle—it’s a lifeline, with orders coming from as far as Garissa, Moyale, and Mombasa, especially from regions grappling with chronic water shortages.

Beyond income, they see themselves as environmental stewards.

“You know these containers could just be burned somewhere, polluting the air and soil,” Musembi said, his gaze following the smoke rising in the distance, from a pile of garbage across the road.

“But here we are, sourcing, cleaning, and giving them new life. Even if it’s without gloves.”

Protective gear

He and the others are painfully aware of the risks, cuts, rashes, and chemical burns, but they have long given up on the idea of protective gear.

“We’ve tried gloves, but they slow you down. They get wet, slippery, and the grip goes. I might have 50 bottles to clean by the end of the day, and then a customer walks in wanting 20 more on the spot,” he says.

Then he shook his head, as if brushing off an old argument.

“There’s no time to be soft. So we just keep going. Maybe it’s not safe, but at least it’s work. And it’s honest.”

Poor drainage and garbage

The challenges they face are as tough as the job itself, with poor drainage in Kariokor regularly flooding their stalls during the rainy season.

"All the water from the upper market flows down here. Sometimes it’s hard for customers to even reach us," Muchaka said.

They endure harassment from county officers and unsanitary conditions, with trash piling up across from their stalls in the road median, drawing flies and spreading a foul stench.

Still, they work from 7 am to 7:30 pm without formal recognition or protection.

Community attitudes are mixed—some admire the traders’ resilience while others mock their work as dirty, but neither scorn nor stigma deters them.

We then meet Chege, a 19-year-old trader and TikTok content creator.

By the time we reached Chege’s stall, he was elbow-deep in soapy water, expertly rinsing a drum as water sloshed around his feet.

When we mentioned that Musembi and Muchaka had sent us to him, he grinned.

"Aah, Musembi na Muchaka? Sawa basi, mko sawa," he said, wiping his hands on a rag. "Karibuni. How do I help you?"

After a brief introduction, we were soon chatting and laughing through the drizzle, but his name carries weight in this place.

Known on TikTok as Price Chege (Drum), he’s built a loyal following of over 9,000 by documenting his trade—scrubbing, sealing, stacking, and selling recycled containers—instead of chasing trends or dancing for likes. His videos offer a raw, hands-on look at the hustle behind the scenes.

"Some people tell me to just go entertain like everyone else. But for me, TikTok is a tool. And I’m selling something real," he said.

Many in the trade, including older workers who spoke anonymously, view it as a means of survival in a city with limited job opportunities and say they would welcome government or NGO support to improve drainage, sanitation, and working conditions.

Patching broken system

In a city where waste often chokes rivers, clogs drainage, or burns in smoky backyard fires, these young traders are quietly stepping in, patching the broken system with bare hands and borrowed tools.

Working without recognition, they turn discarded oil drums and chemical jerrycans into useful items—an unglamorous yet vital form of environmental service that, though informal and gritty, leaves a lasting impact.

With every container they salvage, they not only keep Nairobi’s waterways and air cleaner but also go beyond recycling by creating lasting environmental change through daily effort.

They are reclaiming dignity by carving out income and purpose from Nairobi’s waste, proving that value often emerges without polish or policy.

"We’re just trying to clean the city, one container at a time. Maybe it is not a big job to some people, but it matters. We are cleaning what others throw away, and turning it into something someone else needs," Chege said.

These containers—once used for chemicals, oil, cooking oil, soap, tomato sauce, or other products—are repurposed into water storage drums, animal feeders, mobile sinks, and even makeshift fuel or storage tanks.

With proper cleaning and care, what was once waste becomes a second-hand essential in homes, farms, sanitation stations, and small businesses across Kenya.

If you ever find yourself in Kariokor Market searching for one, just ask for Chege the TikToker or his fellow traders, Brian and Mike—you’ll find them not just selling, but scrubbing, stacking, and transforming Nairobi’s waste into something useful.

Top Stories Today